I’ve pointed out Tony Swatton’s video series in the past; he is a blacksmith for film, television and theatre, and in this short series, he recreates famous weapons from films, video games and other pop culture using real blacksmith and metal-working techniques. If you haven’t seen it yet, this is a great one to start with: Swatton forges the sword “Sting” used by Bilbo in The Hobbit.

Tag Archives: weapons

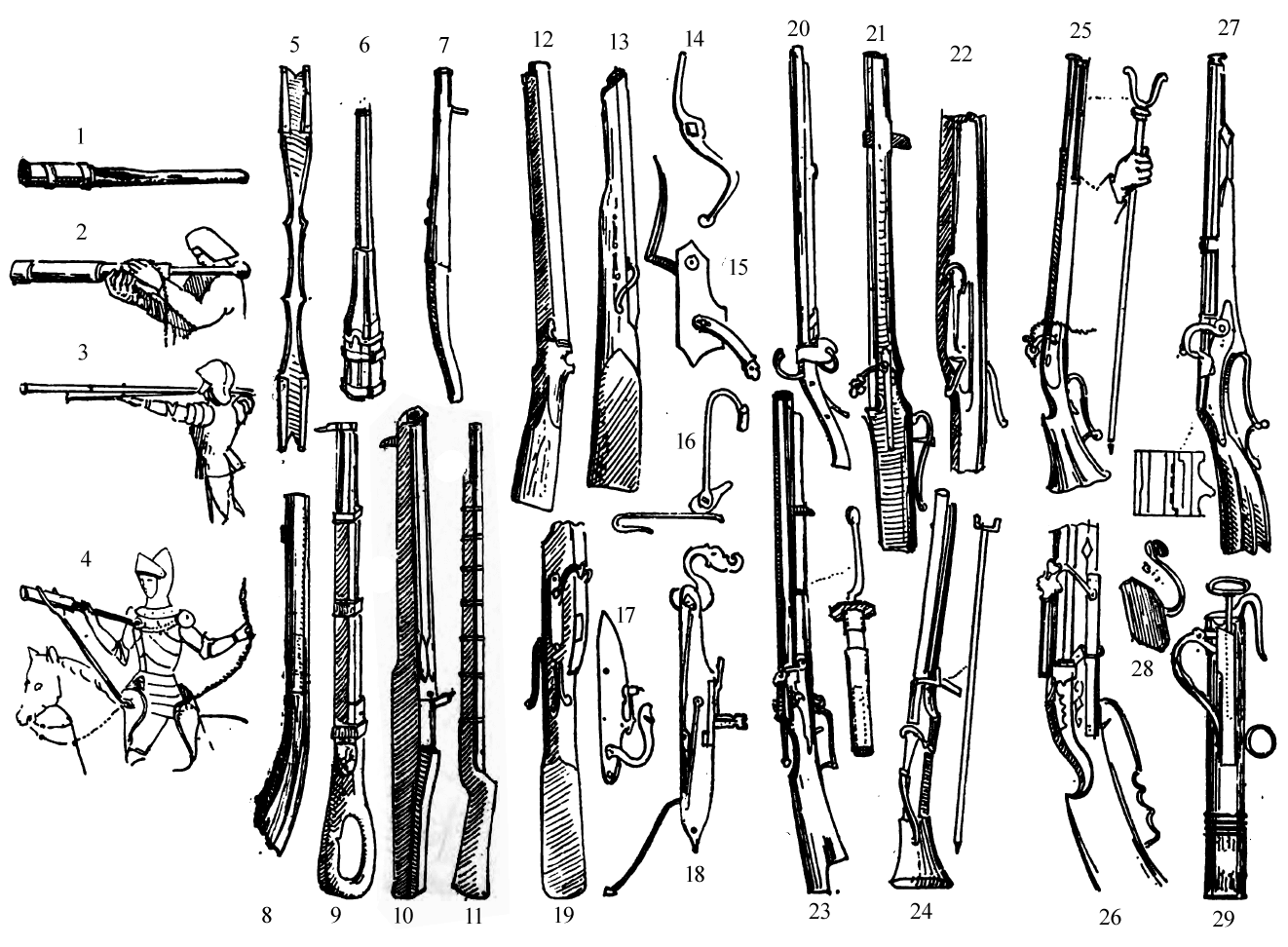

Hand Fire-Arms through History

- Hand cannon for foot soldier in cast iron, belonging to the first half of the fourteenth century. The touch-hole (German, Zünderloch) is on the upper part of the cannon.

- Hand cannon for foot soldier, from a MS. of the end of the fourteenth century. The touch-hole is on the top of the cannon.

- Hand cannon for foot soldier, from a manuscript of the year 1472, in the library of Hauslaub at Vienna.

- Hand cannon for a knight, called a petronel, from a manuscript in the ancient library of Burgundy. The articulated plate armour is characteristic of the latter half of the fifteenth century, though the bassinet has a movable vizor. These hand cannons were in use at the same time as the serpentine arquebuse, and even as the flint and steel arquebuses and muskets, ie till the beginning of the sixteenth century, as may be seen from the drawings, by Glockenthon, of the arms of the Emperor Maximilian I. (1505).

- German hand cannon, fixed on wooden boards or stands, belonging to the beginning of the sixteenth century. The touch-hole is still on the upper part of the cannon. From the drawings of Glockenthon, done in 1505.

- German hand cannon in fluted iron, of the beginning of the sixteenth century, or end of the fifteenth century. It is only 9 1/2 inches in length, 2 inches in diameter, and is fixed on to a piece of oak about 5 feet in length. In the Germanic Museum, where it is wrongly ascribed to the fourteenth century.

- Hand cannon in wrought iron, called a petronel, to be used by a knight. It is of the end of the fifteenth century.

- Hand cannon with stock of the end of the fourteenth century. The touch-hole is on the top of the cannon.

- Angular hand cannon on stock; to be used in defending ramparts. It is a little over 6 feet in length, and the touch-hole is on the top of the cannon. This piece was used in the defence of Morat against Charles le Téméraire (1479).

- Eight-sided hand cannon with stock. The touch-hole, which is on the top of the cannon, has a cover moving on a pivot. This cannon is 54 inches in length, and the balls or bullets about 1 1/2 inch in diameter. It belongs to the first part of the fifteenth century.

- Persian matchlock cannon, copied from the Schah-Namen, in the Library of Munich.

- Hand cannon on stock, end of the fourteenth, or beginning of the fifteenth century. In this piece the touch-hold is on the right side.

- Hand cannon with serpentine, a match-holder, without trigger or spring, invented about the year 1424.

- Serpentine or guncock for match, without trigger or spring.

- Serpentine without trigger, but with spring.

- Serpentine with spring, but without trigger.

- Serpentine lock, without trigger or spring.

- Hackbuss lock with spring and trigger.

- Hackbuss (in German, Hakenbüchse) or hand cannon, with butt end and serpentine lock. It belongs to the second half of the fifteenth century. The match is no longer loose, but fixed to the serpentine, which springs back by means of the trigger. This sort of cannon is generally about 40 inches in length, and it is usually provided with a hook, so that when it is placed on a wall it cannot slip back. The hackbuss without a hook is, as a rule, better made, and was subsequently called arquebuse with matchlock. It had also front and back sights (in German, Visir und Kern).

- Chinese arquebuse.

- Swiss arquebuse of the second half of the fifteenth century.

- Double arquebuse (in German, Doppelhaken). This weapon had two serpentines, or dogheads, falling from opposite points, and was generally used in defending ramparts; the barrel was usually from 5 to 6 1/2 feet in length.

- Hackbuss, loaded from the breech by means of a revolving chamber, a weapon belonging to the beginning of the sixteenth century.

- Hackbuss and gun fork (German, Gabel), from the drawings of Glockenthon; it may also be seen in the engraving of the “Triumph of the Emperor Maximilian I.” From this we see that the hackbuss, or match arquebuse, was used for a long time together with the wheel-lock arquebuse.

- Serpentine hackbuss with match, also called musket. It is also furnished with a fork, called a fourquine in French.

- Hackbuss or musket, with link.

- Serpentine hackbuss with link, also called arquebuse, loaded from the breech by means of a revolving chamber. It dates from the year 1537, and bears the initials W. H. by the side of a fleur-de-lys.

- Eye protector, belonging to a musket in the Arsenal of Geneva.

- Hand cannon with rasp, early part of the sixteenth century. It is entirely of iron, and is called Münchsbüchse (monk’s arquebuse). For a very long time it was wrongly thought to be the first fire-arm ever made, and to have belonged to a monk named Berthold Schwartz (1290-1320), who was also said to have invented gunpowder. This little weapon is about 11 1/2 inches in length, and the barrel 5 inches in diameter. It preceded the wheel-lock, and appears to have suggested the idea of it. A rasp scatters sparks from the sulphurous pyrites by friction.

The illustrations and descriptions have been taken from An Illustrated History of Arms and Armour: From the Earliest Period to the Present Time, by Auguste Demmin, and translated by Charles Christopher Black. Published in 1894 by George Bell.

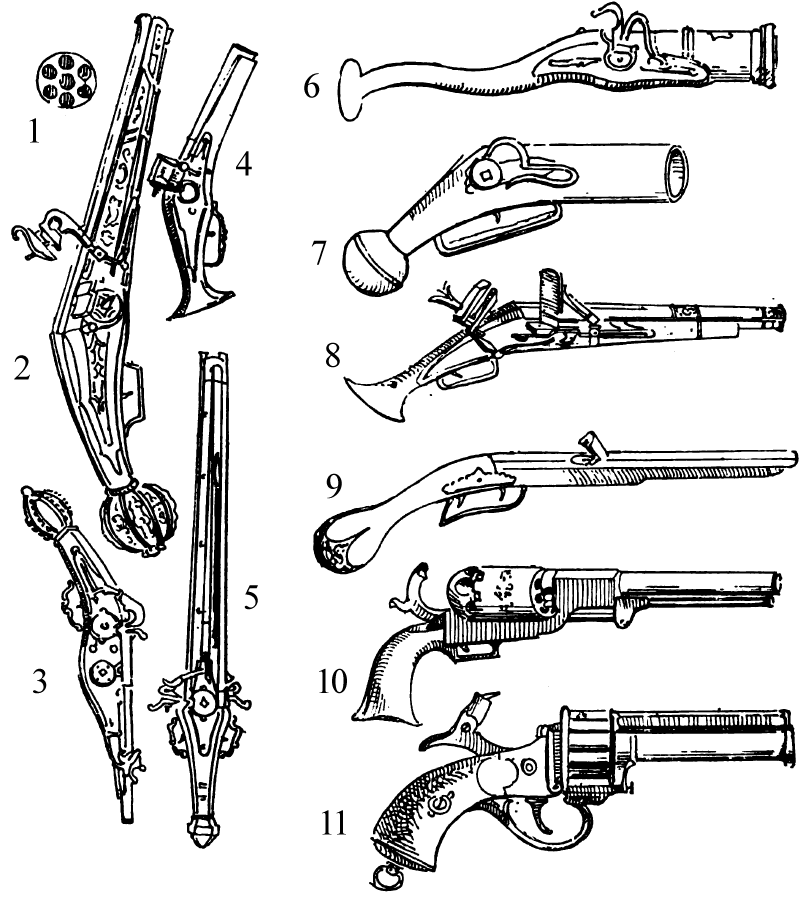

Pistols, 1500-1856

Here is a small collection of typical or notable pistols spanning from the sixteenth century to the middle of the nineteenth century.

- Barrel for number 4.

- Wheel-lock pistol of the sixteenth century. This was the sort of pistol used by the German cavalry, and also by the Ritter, or knights.

- Wheel-lock pistol with double barrel, beginning of the seventeenth century.

- Wheel-lock pistol, firing seven shots.

- Double wheel-lock, end of the sixteenth century. Arsenal of Zurich.

- Wheel-lock and mortar pistol, called in German Katzenkopf, of the seventeenth century.

- Wheel-lock and mortar pistol of the seventeenth century. It is entirely of iron.

- Flint-lock pistol, end of the seventeenth century.

- Pistol with flint-lock, of the beginning of the eighteenth century.

- Colt’s revolver, invented by Samuel Colt, of the United States, in 1835.

- Mat revolver, invented a short time back by M. Le Mat.

The illustrations and descriptions have been taken from An Illustrated History of Arms and Armour: From the Earliest Period to the Present Time, by Auguste Demmin, and translated by Charles Christopher Black. Published in 1894 by George Bell.

Friday Links on Display

It’s another Friday, and another September. This always seems like the busiest time of the year for the whole entertainment industry. Some of you may have gotten a four-day week this past week, but for most of us, it was an eight-day week. So take a seat, relax, and enjoy these links for a few minutes:

Huffington Post has an interview with props master Peter Bankins. Bankins has been a prop master in film for the past 25 years, working on movies such as Young Guns, Grumpier Old Men, Erin Brockovitch and many more.

On the other side of the pond, Farfetch has a short photo essay called “Our Day With Thomas Petherick“. Petherick is a young prop maker and set designer working mainly on fashion photography shoots.

Bill Doran and his wife created a fairly detailed set of armor and weapons from the video game Skyrim for this year’s Dragon Con. He details the lengthy build process as they fashion parts out of wood, EVA foam, Worbla, resin and more.

Finally, here is a familiar face; I was displaying some of my props at last month’s Burlington Mini Maker Faire. Coffey Productions was going around filming the various exhibits, and shot this video of me talking about my props and my book. Check it out!

20000 Objects in Opera Property Room, part 5, 1912

The following is the fifth portion of an article which first appeared in the New York Sun in 1912. You can catch up on the first part, the second part, third part and the fourth part.

In addition to the mass of less frequently used properties which are distributed among the storehouses there are at the opera house itself five large rooms filled with hundreds and hundreds of the objects oftenest in demand. In one of these rooms, which is called the armory, are rows of helmets, great stands of spears, racks full of guns, innumerable swords, including the famous one of Siegfried, the white one of Lohengrin and that of Telramund. Here is Caruso’s armor, which, as he dislikes to wear or carry anything heavy, is made of aluminum. His helmets are of aluminum too. These stage weapons are never sharp enough to do any damage, even if some one accidentally got in their way.

The guns are the real thing and are loaded with powder. A permit to keep explosives on the premises has to be had every time an opera is given in which guns are fired or conflagrations imitated.

In one of the property rooms at the opera house, which is always spoken of as “Frank Furst’s room,” an employee is generally at work rubbing up gun barrels, swords and armor, or polishing brass armlets. Guns are used not only on he stage, as in “Tosca” and “Carmen,” but off stage in taking up cues.

If a great crash is to be produced half a dozen stage hands are armed beside them with a prompt book following the score. As the cue approaches he counts, “one, two, three, four, five!” At five they fire simultaneously, while at the same time there comes a clap of stage thunder. The resulting noise is big enough for any kind of a crash.

A curious phase of the property department’s work is the way it sometimes has to dovetail a job with some other department. For instance, in the last act of “Tosca” there is a flag which floats on the top of the tower. It really does float, the breeze blowing it with every appearance of naturalness. An electric fan adjusted behind the side scenes provides the breeze. In this case the flag is put in place by the property department, while the electric fan belongs to the electrical department, which must see that it is set up and running.

In the second act of “Madama Butterfly” several large Japanese lanterns with standards are brought in by Suzuki and set about the stage. Lights are burning inside them. The third act opens with the same scene after a lapse of several hours, which passage of time is indicated by having the lights in the lanterns flicker and go out one by one. This is the way it is done. When the lanterns are brought on they contain lighted candles which come under the head of properties and which therefore are put in and lighted by some one in that department.

When the curtain goes down a property man takes out these candles. Then an electrician sees that the standards are placed over metal plates in the matting, Suzuki having set them in approximately the correct position. Then he puts in electric bulbs, wires from under the stage are connected with the metal plates, contact is secured through the base of the standard and the resulting light is then turned on and off from below to simulate a flickering candle flame. After the scene the electrician comes and gets his bulbs before the property man can carry off the lanterns.

This article will conclude in a later post. It was originally published in the New York Sun, February 25, 1912, page 16.