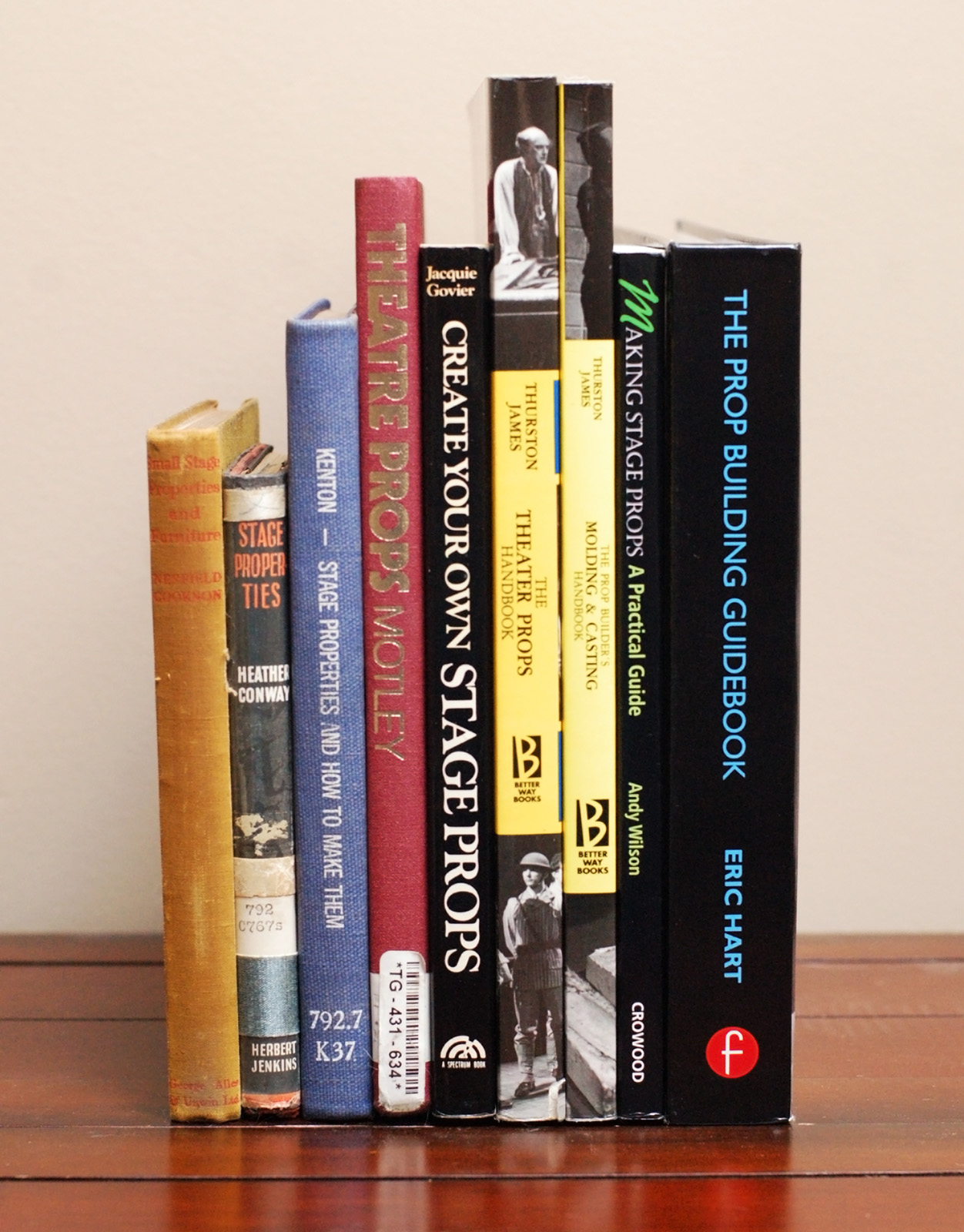

I wanted to make a “Top Ten” list of prop making books, but it turns out there aren’t enough to do that. As it is, I have to include one that’s nearly 80 years old. In other words, books dealing solely with how to make props are few and far between. Plenty of books exist for the various specialties of prop making, such as woodworking, sewing and sculpting, but these do not deal with the specifics of prop making, which often uses a more limited range of materials and has an emphasis on faster techniques rather than slow processes. In addition, making props for the stage or screen has its own considerations beyond just making an object look good.

So, with my own book coming out this week, I thought I would step through the prop making books which have come before. I am not including books such as Amy Mussman’s The Prop Master or Sandra Strawn’s The Properties Director’s Handbook. Though both of these have sections on making props, they are more geared toward the management of propping a show or running a prop shop. There are also plenty of books on set design or stagecraft which include a chapter on props, but these rarely delve into the subject with enough detail to be useful. If anyone knows of other prop making books, let me know in the comments; I think I found them all, though.

Small Stage Properties and Furniture, by Mrs. Nesfield Cookson (UK, 1934)

I quite liked this book in terms of layout and how comprehensive it was for its time. What really kills it is its datedness, both in terms of materials and in the stilted and formal language it uses, making it difficult to follow in parts (and yes, the author is actually credited as “Mrs.”). Still, it is divided up into useful sections, such as furniture, papier mâché, molds and modelling, jewellery and painting. It also has two chapters to cover some “catch-all” categories. One is on armatures and foundations, the other on projections and ornamentations (“projections”, in this case, refers to three-dimensional details which stick out from the prop’s surface). The material covered in these two chapters are useful for the props artisan but the information is often overlooked because it does not fit neatly into one category or the other, particularly when you divide prop making into specific materials and tools. It is clearly illustrated in parts, though not nearly enough.

Stage Properties, by Heather Conway (UK, 1959)

This book is a disappointment. It spends a scant 27 pages on the making of properties; the techniques are the same dated ones (sized felt, perforated zinc, papier-mâché, et al) found in better detail in other books on this list. The bulk of this book is spent on “reference” for historical plays. Each of the main “theatrical periods” in vogue at the time, such as Ancient Greece or Elizabethan England, are described in quick detail, with line drawings of the most archetypal objects, such as goblets or sword handles. It reminds me of The Theater Props What, Where, When, by Thurston James, and is especially useless in an era of Internet searching. It would certainly be nice to have a quick reference for the common objects of any particular era or period, but this book does not even go that far.

Stage Properties, and How to Make Them, by Warren Kenton (UK, 1964)

This book is an improvement in that the illustrations are shaded, thus imparting more detail. It is also the first in our list to mention plastics, but only so far as to say a) they exist, and b) they are too expensive for the prop maker to use. Still, I like the way this presents the more traditional aspects of prop making, giving a description on the left page and various illustrations on the right. The basic techniques it covers only last for about twenty pages. The rest of the book falls victim to what many prop making books succumb to; rather than trying to break down the craft into simpler components, or attempt to describe an approach to building props, it simply lists common props (candlesticks, masks, powder horns, etc.) and describes one way to make them. Nonetheless, it does so in a way that is clear and approachable.

Theatre Props, by Motley (UK, 1975)

The “Motley” listed as the author is not someone’s name; rather, it describes how the book is written by a diverse set of people. It has seven chapters written by five people, with a sixth writing the introduction. This does give it an advantage of avoiding a single prop maker’s point of view or experience. The chapters included are strange in their selection: “Hand Props and Soft Props”, “Moulding and Casting”, “Light Fittings and Fires”, “Special and Trick Props”, “Carpentry Props”, “Flowers and Foliage”, “Jewellery and Decoration”. While it is nice to get away from the “papier mâché and chicken wire” approach the previous books take, this book is far from comprehensive. It is more like a collection of magazine articles compiled into a single volume. Still, you can tell from the chapters that, though not a complete guide to prop building, this book contains useful  information that is absent from many other prop books. It is also the first on our list to feature photographs in addition to illustrations.

Create Your Own Stage Props, by Jacquie Govier (UK, 1984)

This book is aimed at the amateur or school theatre, and as such, feels very “crafty”. It also takes a step back in time and uses only illustrations, rather than including photographs. As a craft book for amateurs, it is actually quite well; it covers a lot of the basics, and is the first book on our list to deal with foam carving, one of the staples of any prop shop. For the budding professional though, the techniques can seem a bit embarrassing, even when you forgive the book its age. Even at the time, professional theatres were vacuum forming and using fiberglass, not to mention welding steel and constructing real furniture. They certainly weren’t wrapping glue-soaked string around a balloon.

The Theater Props Handbook, by Thurston James (US, 1987)

The first US book on our list is also one of the most well-known. While it attempts to be a comprehensive guide to all manner of theatrical property construction, the layout and organization is quite strange. James puts the chapters in alphabetical order, meaning you go from reading about “eyeglasses” on one page to reading about “fire” on the next. The chapters also differ greatly in scope; one chapter is dedicated to “construction techniques”, while another deals simply with “confetti”. The chapter on “construction techniques” is broken down to a few different materials, though one of the sub-headings is “making a butter churn.” Later, he has a whole chapter titled “Gramophone.” Why gramophone gets its own chapter while butter churn is included in a larger chapter is beyond me. Basically, this book is a collection of props which James has built and tricks James has learned with no attempt to find the standards of our industry or organize any of the information. If you want to know how to construct wooden furniture, head to the “Rehearsal Furniture” chapter, but if you want to know how to cut wood on the jigsaw, it’s back to the section on making a butter churn. This book has a lot of great information and tricks—don’t get me wrong—but only if you can find it. And don’t even get me started with how the columns are laid out on the page! Every page has two columns of text. However, you switch from the left column to the right whenever you reach a new sub-chapter, rather than following each column all the way down the page.

The Prop Builder’s Molding & Casting Handbook, by Thurston James (US, 1989)

James is perhaps more well-known for this book, and it has probably done more to cement his legacy as a writer of props books. Unlike his first book, this one is laid out in a very organized manner, giving a general introduction and then stepping through each of the materials in turn. The introduction even has a photograph comparing the various materials covered in the book, which helps clue you into what will follow. Though the book is nearly a quarter of a century old, the techniques described still hold true. A few of the materials have better alternatives available, and a couple have become obsolete, but on the whole, we still use most of what is in the book. Materials like plaster, latex, silicone rubber, alginate and plastic resins are some of the workhorses of the props shop, and any advances have not made this book any less useful. Like the other James’ books, it has the same confusing column layout where you switch from the left column to the right and back again several times on a page.

Making Stage Props, by Andy Wilson (UK, 2003)

Wilson has written one of the most up-to-date and well-organized prop building books. This book covers a great deal of the materials and methods one might actually use in a professional theatre’s prop shop. While it has a great deal of information in it, it does not have everything; for example, it covers steel, but none of the other metals one might use, such as aluminum or brass. It covers upholstery, but nothing else about fabric. In fact, it skips over a lot of the craft and soft goods portions of prop making, and omits entirely any mention of plastic sheet goods such as plexiglass. It is also uneven in the amount of space it devotes to various topics. The section on turning, for instance, spends over nine pages discussing the setup of the lathe, the various tools used, and methods employed. This is not to say the lathe is not a useful tool for a props shop — it is — but a machine like the table saw is far more frequently used in props shops, and it gets only an off-handed mention in the middle of a sentence. Likewise, Wilson spends a few paragraphs and a photograph on “fire cement”, which is one of his specialties but practically unheard of in the majority of props shops. This would be fine if you had an infinite number of pages to cover everything, but not if your book neglects to include how to make a single stitch or seam in fabric. The photographs and illustrations are nice, though they are in black and white. None of the books on our list, in fact, use color photographs, nor do any talk about prop making in film or television.

The Prop Building Guidebook: For Theatre, Film, and TV, by Eric Hart (US, 2013)

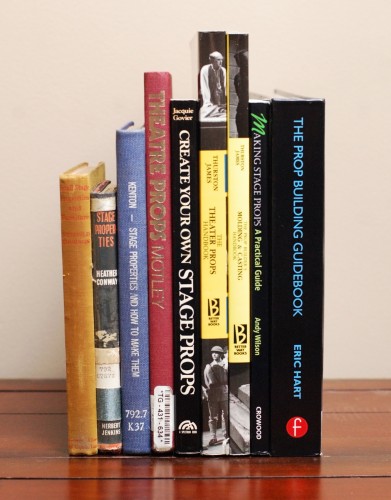

Yes, this is my book. While writing it, I have attempted to pull all the good stuff from the aforementioned books while avoiding all the criticisms. I’ve looked at a variety of prop shops, both through interviewing various prop makers, visiting shops of all sizes, and through my own experience working around the country, to avoid prescribing one single way to build props. In the photograph above, you can see it is the largest and most comprehensive book, and it is also the first to feature color photographs and illustrations. I have geared the book to be useful to all levels of both amateur and professional, but I avoided making it “amateurish”; even if you have no budget, you can still work to high standards. My hope is that it will be a major leap in prop-making books to a new standard of professionalism that better reflects what our industry is like.