Molière (1622-1673) performed his plays in Paris, where theatres were inside and lit by candles. He performed at the salle du Petit-Bourbon at the Louvre, followed by the Palais-Royal. Finally, he performed some of his works at Versailles for King Louis XIV. We know quite a bit about the acting styles, the sceneography, and the costumes of his time. But how were props dealt with? Where did they come from, and who was in charge of them?

We can piece together information of how Molière acquired and used props by looking at the general theatre conditions in France at the time. We also have some actual surviving props from his theatre company, and several record books. The picture which forms is similar to conditions in theatres of adjoining countries and eras, such as Elizabethan England. There is some form of bureaucratic control in the theatre buildings, including people responsible for commissioning props. There does not appear to be “prop makers” or “prop masters” per se; rather, the theatre troupes, composed of the actors and a manager, are responsible for maintaining their own stock of props for the shows they perform (this, of course, is where the term “property” comes from).

General Theatre Conditions

The French theatre in Molière’s time customarily employed several people. The decorateur, or theatrical painter, decoraged the stage and auditorium. He worked with the machinest to produce all the scenery and machines.

The official now called the Régisseur in those days went by the name of premier garçon de théâtre; he had to superintend all the properties and keep account of them, to supervise the supers or assistants used in the different plays, and to see that “all who appear before the public are decently dressed and wear proper shows and stockings.” He also performed small parts, rang the bell when the play was to begin, and warned the actors when it was their turn to enter. Under his orders there were four stage-servants, half “machinists,” half call-boys.

A History of Theatrical Art in Ancient and Modern Times: Molière and his times, by Karl Mantzius; Vol 4, 1905; pg 97.

We can glean some more information from L’Impromptu de Versailles (The Impromptu at Versailles, written in 1663). This one-act farce by Molière was written in response to criticisms against him, and the actors in this troupe played exaggerated versions of themselves as they rehearse a new play. We can pull off-handed remarks about the props and their use to construct a bit of information about standard practices of Molière and his company. For example, in scene IV, Molière instructs his actors: “Those coffres, Mesdames, will serve you for easy-chairs.” The actors obey; we can assume that the actors would have been familiar with using rehearsal furniture at least some of the time, otherwise they would have expressed objection or confusion. The French word “coffres” translates to “chests” or “trunks”. As for the easy-chair, the fauteuil was an upholstered arm chair popular at that time.

In a previous post about Molière’s move from Le Petit Bourbon to the Palais Royal, we pick up clues that props (along with scenery and machinery) were stored behind the curtain of the theatre.

Surviving Props

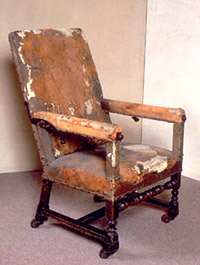

La Comédie-Française is one of the state theatres of France. In its collection is the armchair used by Molière during Le Malade imaginaire (The Imaginary Invalid).

The chair is a Louis XIII style armchair made of wood, upholstered with black sheepskin, and set on casters. It is 4 feet by 2 feet 2 inches by 2 feet 8 inches (123 x 68 x 82 cm). It was first used in 1673 by Molière for the premiere of Le Malade imaginaire, and is the chair he died on during the performance. It was used by successive actors playing Argan until 1879. That’s 209 years, math-wizard. At that point, it had become so worn that a replica was made for the current Argan and the original placed on display.

A nitecap worn by Argan (played by Molière) is also housed there.

Engravings

An engraving of a 1674 remount of The Imaginary Invalid (the year after Molière’s death) shows the stage picture.

The armchair appears to be the only set prop. Set dressing is nonexistent. The only hand props are the fan, and the spears held by the guards on the far sides of the stage. Really, the fan should be considered a personal prop. At this time in France, it was the actress’s (and actor’s)Â responsibility to costume herself, even at great expense. Conceivably, the fan could have been her personal property as well. Since the plays at the time used archetypal characters, and the settings were very consistent, one might surmise that props were mostly pulled from their stock, which would have been fairly modest. After all, if they used the same armchair for 209 years, the modern convention of purchasing and constructing new props for every single production was probably not practiced at that time.

Registers

Other information for reconstructing the public performances are found in 4 existing accounting books kept by Molière’s company. Basic production costs covered include lighting, heat, printing and posting of playbills, and wages to production staff and theatre personnel, such as the concierge, copyist and prompter, orchestra, ticket-seller and ticket-taker, door monitors, the décorateur, actors’ domestics, ushers, and candle-snuffer. Extraordinary expenses include building and operating stage machines, fabricating costumes and stage properties, wages paid to singers, instrumentalists, and dancers.

One of these accounting books is the register of Charles Varlet de la Grange. He was an actor in Molière’s troupe and kept a daily account of the business dealings, as well as major events in the members’ lives. You can check out a description and photos of La Grange’s register, or read Édouard Thierry’s edition (in French). By studying this register, we can find out what props were used in his various plays, and whether there were any “prop” tricks. For example, in L’École des femmes (The School for Wives), first performed in 1662, props mentioned include a chair in III.2 and a purse with some counters to serve as coins for I.4.

According to La Grange’s reports, Le Malade imaginaire received a lavish staging with “the prologue and intermèdes filled with dances, vocal music, and stage properties”. The theatre troupe had to order the wood, iron, and canvas for carpenters, upholsterers, and painters. The first two carpenters were named Caron and Jacques Portrait. The workers were paid by the day. For its 1674 revival , La Grange listed the following production expenses: menuisiers (carpenters), ouvriers et assistans (workers who operated the machinery and set-changes), 2 laquais et decorateur (2 lackeys and the set-designer), and surcroist de chandel (candle supplement).

Similar records can be found in registers by La Thorillière and Hubert, two more members of Molière troupe. You can read the original register of La Thorillière (in French) for more fun.