This is the second excerpt in a magazine article in Belgravia, an Illustrated London Magazine, published in 1878. It describes the history of props in Western European theatrical traditions up to the late nineteenth century. I’ve split it into several sections because it is rather long and covers a multitude of subjects, which I will be posting over the next several days.

Stage Properties by Dutton Cook, 1878

In the ‘Tatler,’ No. 42, [Eric: published July 16, 1709] Addison supplies a humorous list of properties, alleged to be for sale in consequence of the closing of Drury Lane Theatre. Notice is given, in mimicry of an auctioneer’s advertisement, that a ‘magnificent palace with great variety of gardens, statues, and waterworks, may be bought cheap in Drury Lane, where there are likewise several castles to be disposed of, very delightfully situated; as also groves, woods, forests, fountains, and country seats with very pleasant prospects on all sides of them: being the moveables of Christopher Rich, Esquire, [the manager,] who is giving up housekeeping, and has many curious pieces of furniture to dispose of, which may be seen between the hours of six and ten in the evening.’ Among the items enumerated appear the following:

A new moon, something decayed.

A rainbow a little faded.

A setting sun.

A couch very finely gilt and little used, with a pair of dragons, to be sold cheap.

Roxana’s nightgown.

Othello’s handkerchief.

A serpent to sting Cleopatra.

An imperial mantle made for Cyrus the Great, and worn by Julius Cæsar, Bajazet, King Henry VIII., and Signor Valentini. The imperial robes of Xerxes, never worn but once.

This was an allusion to Cibber’s feeble tragedy of ‘Xerxes,’ which was produced at the Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre in 1699, and permitted one performance only.

The whiskers of a Turkish bassa.

The complexion of a murderer in a bandbox: consisting of a large piece of burnt cork and a coal-black peruke.

A suit of clothes for a ghost, viz. a bloody shirt, a doublet curiously pinked, and a coat with three great eyelet holes upon the breast.

Six elbow chairs, very expert in country dances, with six flowerpots for their partners.

These articles of furniture, of a mechanical or trick sort, employed in pantomimes, are referred to in a letter published at a later date in the ‘Spectator’ from William Screene, who describes himself as having acted ‘several parts of household stuff with great applause for many years. I am,’ he continues, ‘one of the men in the hangings of the Emperor of the Moon; I have twice performed the third chair in an English opera; and have rehearsed the pump in the “Fortune Hunters.”‘ Another correspondent, Ralph Simple, states that he has ‘several times acted one of the finest flower-pots in the same opera wherein Mr. Screene is a chair,’ &c.

A plume of feathers never used but by Å’dipus and the Earl of Essex.

Modern plots, commonly known by the name of trapdoors, ladders of ropes, vizard masques, and tables with broad carpets over them.

A wild boar killed by Mrs. Tofts and Dioclesian.

Mrs. Tofts, as the Amazonian heroine of the opera of ‘Camilla,’ by Marc Antonio Buononcini, was required to slay a wild boar upon the stage. A letter published in the ‘Spectator’ professed to be written by the performer of the wild boar: ‘Mr. Spectator,— Your having been so humble as to take notice of the epistles of other animals emboldens me, who am the wild boar that was killed by Mrs. Tofts, to represent to you that I think I was hardly used in not having the part of the lion in Hydaspes given to me. …As for the little resistance which I made, I hope it may be excused when it is considered that the dust was thrown at me by so fair a hand.’

The list concludes:

There are also swords, halberds, sheephooks, cardinals’ hats, turbans, drums, gallipots, a gibbet, a cradle, a rack, a cartwheel, an altar, a helmet, a back-piece, a breast-plate, a bell, a tub, and a jointed baby.

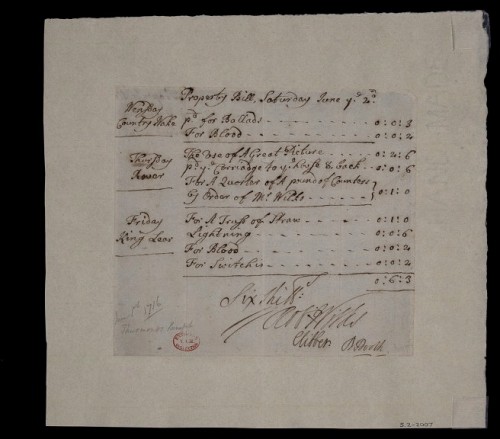

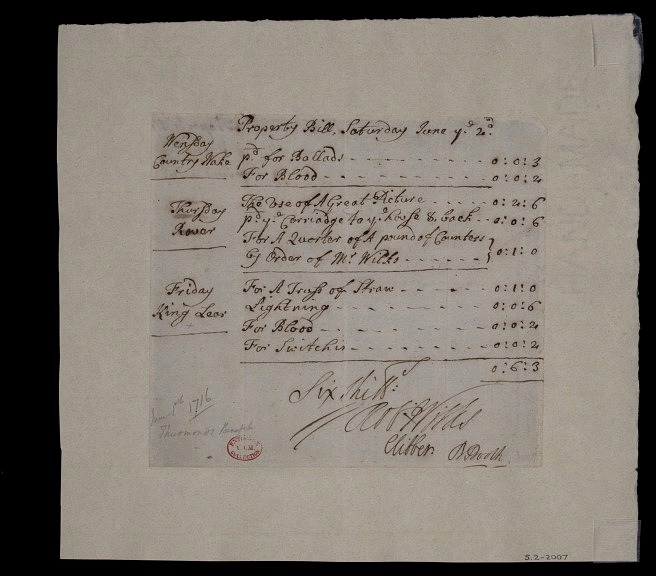

But this supposititious catalogue is scarcely more comical than the genuine inventory of properties, &c., belonging to the Theatre Royal in Crow Street, Dublin, 1776. A few of the items may be quoted:

Bow, quiver, and bonnet for Douglas.

Jobson’s bed. (For the farce of’ The Devil to Pay.’)

Juliet’s bier.

Juliet’s balcony.

A small map for Lear.

Tomb for the Grecian Daughter.

One shepherd’s hat.

Four small paper tarts.

Three pasteboard covers for dishes.

An old toy fiddle.

One goblet.

Twenty-eight candlesticks for dressing, and six washing basons, one broke, and four black pitchers.

Eleven metal thunder-bolts, sixty-seven wood ditto, fivo stone ditto.

Three baskets for thunder balls.

Rack in ‘Venice Preserved.’

Elephant in ‘ The Enchanted Lady,’ very bad.

Alexander’s car.

One pair of sea-horses.

Six gentlemen’s helmets.

Altar piece in ‘ Theodosius.’

The statue of Osiris.

Water-fall.

Frost scene in ‘ King Arthur.’

One sedan chair for the pantomime.

The scaffold in ‘Venice Preserved.’

Several old pantomime tricks and useless pieces of scenes.

(Dutton Cook. “Stage Properties.â€Â Belgravia, vol. 35. 1878: pp. 284-286.)