For those of you in North Carolina, the Maker Faire NC is happening tomorrow at the State Fairgrounds in Raleigh. I won’t be there, but the Alamance Makers Guild (where I am a member) will have a copy of my book you can peruse through. And of course, being a Maker Faire, there will be tons of other cool things to see and do.

How to be a Retronaut has a few cool photographs from behind the scenes at Madame Tussaud’s in the 1930s. Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum is still going strong today, and I’ve known prop people who work there, maintaining all the statues.

Adam Savage talks about how being under a deadline can actually improve your projects because it forces you to be more creative. Of course, he uses plenty of examples from his prop and model building days. And there’s a photograph of him in an alien costume.

A California couple bought a house and discovered it had a fallout shelter which was perfectly preserved from 1961. Check out the article for some awesome photographs of product packaging from that time period.

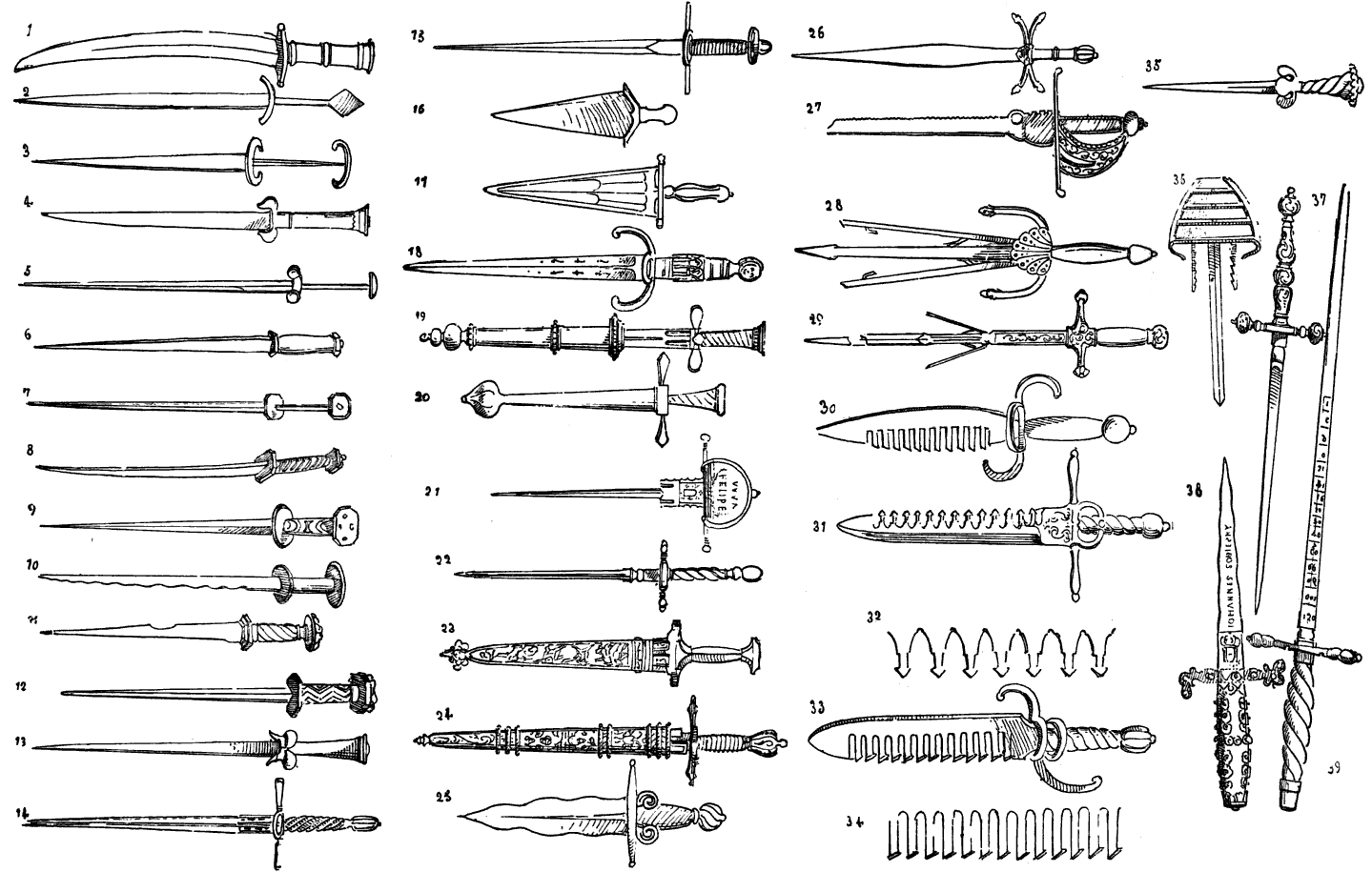

Tony Swatton makes stage combat swords for stage and film. Here is a video where he forges the sword from He-Man. And then he destroys a car with it. I’ve linked to this web series before; every week, he has a new episode showing the creation of a sword or other weapon from film, TV and video games. It is a very insightful view into all kinds of metal working techniques.