This article comes from a 1927 article in The Christian Science Monitor. It has some interesting examples of how props people shopped and sourced articles from nearly ninety years ago. I was also amazed that a university had classes in props back then.

Haunting the antique shops is a regular part of the duties of the “property man” in any well-organized theater, and “property hunting” forms part of the curriculum of Yale University Theater, established last year under the direction of Prof. George P. Baker, formerly of Harvard University.

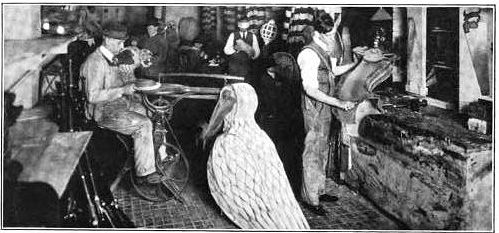

One student in charge of properties is given a crew of from six to eight assistants, varying according to the size of the production. Early in the year it is the business of “props” to make friends with all the second-hand men and antique dealers in town and find out those who are willing to rent their goods for a small nightly sum.

As soon as the list of “props,” furniture and small article need in the play, has been made out, the crew assembles and two or three are chosen to visit the antique dealers. The explorers roam the town, up State Street and down Grand Avenue, and across to Chapel Street in excited quest of trophies that may range from hair trunks to sofas and strings of shell for a what-not, from ladder-back chairs to weaving looms or a case for an opera hat.

Some of the articles are bought outright and added to the theater’s permanent collection, appearing from year to year. These are staples, such as spinning wheels, carved chests, artificial flowers, dishes, firearms, sets of “book-backs” for sham library shelves, pottery, electric doorbells and telephones, beside innumerable small adjuncts such as writing materials, sewing and knitting paraphernalia, photographs and knives, all of which are classified and kept in marked boxes, ready for such directions as “Tooby enters from the garden carrying a bouquet of roses. Tiptoeing to the table, he places them carefully in a bowl and, seizing the paper knife, begins slitting the mail.”

Costume plays make heavy demands on the property pantry for family portraits, reticules, antimacassars, highboys, marble-topped tables, rag rugs, nail kegs and other household incidentals, a list of which sounds like a will in probate.

For such as these, the antique shop, the Salvation Army store, even the junk dealer has his uses, and in some cases near-by villages are scoured for specimens of the period. One scene laid in the middle of the last century was supposed to take place in a mid-western “parlor,” and called for a clock with a scene painted on the front. It was found in a shop in West Haven and brought in, lurching dejectedly, but embellished with a brave sweep of ocean. It was so decrepit that no one thought of stuffing the spring with cotton. In the middle of the play it suddenly came to life, ticking sonorously through the entire act, much to the actors’ discomfiture.

Old houses which are being torn down are a prolific source of “props” and are especially useful to the scene designer. Mantels, cornices, doors, window frames, and even entire fireplaces often are bought up for a song, later to be utilized as part of a “set.”

In one case the designer was in despair over a garden scene where he must produce a fountain. The usual expedients such as canvas stretched on wire netting and painted produced dolefully squat dolphins. Papier mache succeeded little better. Finally, happening to pass the weedy yard where a house was being torn down, the designer saw the very thing he wanted lying half matted in grass.

He strode in, bargained with the wrecking company, and carried his find back to the theater. For $2 he had bought what nearly a week’s work had failed to achieve.

Originally published in The Christian Science Monitor, May 3, 1927; “Yale Theater ‘Props'”, special correspondence, page 8.