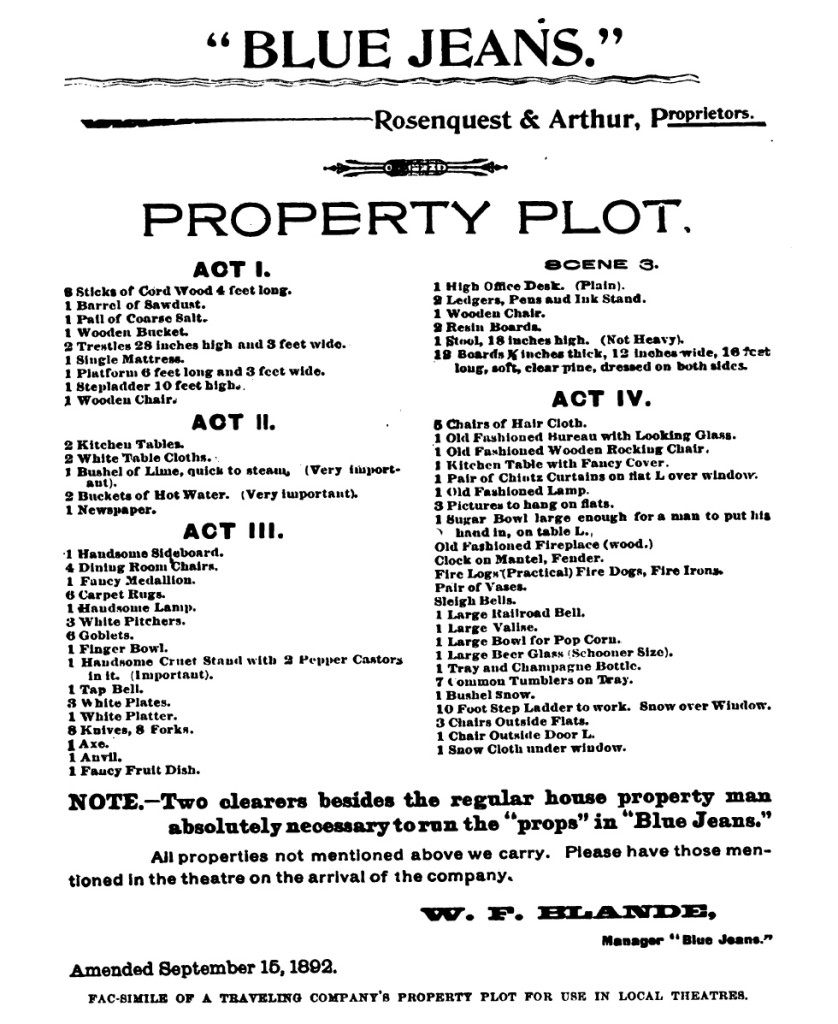

The following is a delightful first-person account (author unknown) of life in the property department. It dates way back to 1895, but many of the challenges of the job remain the same:

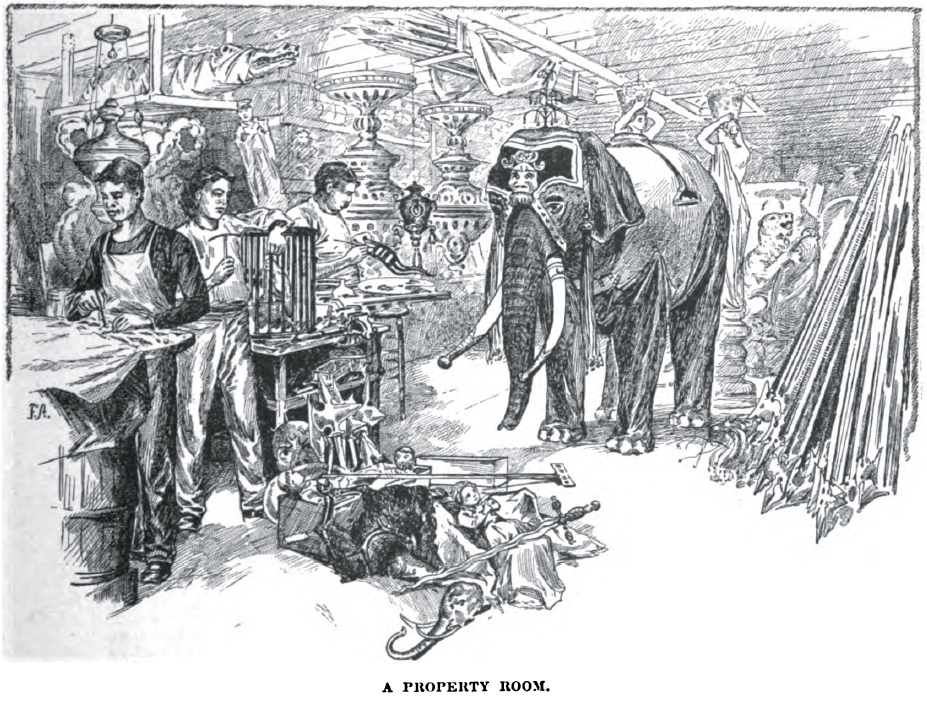

Not exactly an artist—not by any means a mechanic—it is hard for me to say exactly what head I come under. I remember there was trouble the last time they took the census, for my wife would not hear of my being described as a “property man,” through being afraid those stupid Government officers might think me a man of property and go charging me house duty and income tax, and all sorts of things. A hollow kind of life, do you call it? Well, that’s a matter of opinion. Not if it’s done conscientiously, I say. That poet I have heard of must have had me in his eye when he wrote “Things are not what they seem.” It is my mission to make the unreal appear to be real, and whatever you may think about the usefulness of that pursuit as a help to happiness in a respectably-conducted state, the property man is generally more successful in his aim than the actor who looks down upon him. I dare say they never give it a moment’s thought, but the British drama would be a poverty-stricken article without the help of the property man.

King Richard having to go on without a scepter would never be able to render Shakespeare true to nature, and what becomes of your classics, like The Courier of Lyons, if the mail guard isn’t shot at the proper moment? Yes, I have known more than one swagger tragedian have his comb cut through offending the property man. Particularly do I mind an Othello on a sofa with one of the legs sawn through by a gentleman in my line of business as revenge for the swagger tragedian’s bad temper for a whole fortnight. When he and the sofa and the curtain came down all together I thought the roof would have been lifted with laughter. The property man had gone home before the last act, or I am sure there would have been a real tragedy that night—and without any of the Shakespearean dialogue either.

A noble occupation surely, and a strain upon the mind certainly. You are always in terror of forgetting something, and forgetfulness has led to many new readings of popular plays. I recollect omitting to furnish a Hamlet with his tablets. He dived into his cloak for them, and they were not there. So he had to make his notes on imaginary ones, and the next day the newspapers raved about the magnificence of the new reading. Yet the credit belonged to the property-man, who never had any thanks for making the man’s reputation. A week of the legitimate is a regular load on the brain, and those historic plays are enough to drive you mad, what with the banners of this army and that, and the spears and the swords, and the rapiers and the banqueting scenes. Did I ever fit up The Old Toil House?

You’ll be asking me if I ever saw Joe Cave next. Ah! there’s a play for you—full of interest and movement, and those last dying orations for Jack Bunnage—as pretty a bit of poetry as you wish to clap eyes on. None of your drawing-room pieces for me—with their letters and lockets and fans and imitation vases and folderols. Good, honest properties are what I like—something that can be seen from the front with the naked eye and setting the audience wondering how much they cost. Jealous of real horses and cabs and saddle-bag furniture for the interiors? Not a bit of it. Live and let live, I say. Many a property feast have I put on in my time. The public expects property feeds in the legitimate. Sit Macbeth down to a table and ask his guests to drink out of anything but empty goblets, or pretend to do anything in the eating department except fool about with red-cheeked apples before Banquo comes in, and the public would hiss the play off the stage. No, sir, they will not stand any desecration of Shakespeare, and I pity the first Lady Macbeth who dares from the royal table to eat soup with a spoon. It would never do. The playgoer does not expect real food in a Shakespearean piece. He would object to it as a desecration and a degradation. He will permit no interference with the functions of the property man. On the other hand, provide Mrs. Puffy with anything save an honest hot steaming meat pie for The Streets of London and the house would be wrecked.

“Harlequin’s Leap.” Los Angeles Herald, 23 Feb. 1895, p. 11.