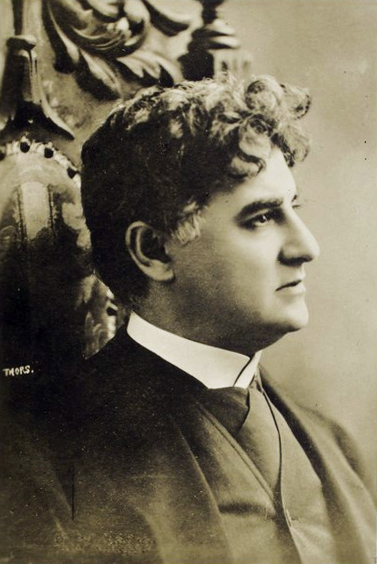

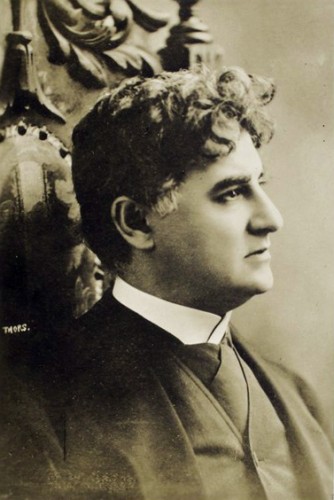

The following is excerpted from an article entitled “How and When David Belasco Goes Hunting for Atmosphere”, written by Adolph Klauber, which first appeared in The New York Times on October 2, 1904.

“Gentlemen, I have found some pawn tickets–in this room above all others in my house! There under that pile of music!”

“Pawn tickets! Anton! His cuckoo clock–two dollars.”

“That was the first thing I missed–that cuckoo–evenin’s.”

The foregoing is a bit of conversation indulged in by Miss Houston of Houston Street and the musician friends of Herr von Barwig, who came to town last Monday night in the person of David Warfield, at the Belasco Theatre. The dialogue in itself is only important as illustrating a point–the point of this discussion on atmosphere in the theatre and how David Belasco goes out to get it.

It’s an interesting process to watch, and a lot of people who gasped and said: “Ah, how very natural,” “Just the sort of room real people live in,” and “Don’t it look just like an old print,” with other comment of the usual sort that people indulge in when a master of stagecraft reveals his finished work, would have gasped several times more if they could have witnessed the making of this reality and understood how many seemingly trivial details go to create the sum total of naturalness on the stage. The importance of lights, the necessity for correct scenic accessory, the value of color on the emotions–these are rather old and hackneyed themes dragged out and dusted and set up to be admired every time a manager comes along with a play in which the scenes are laid somewhere near home in an environment with which most people are supposed to be familiar. It is different if the place of action, for instance, is some rocky foreign coast or cheerless desert place, where the artist may let his imagination run riot, satisfied that few if any people will know whether his picture does or does not look like the real thing. But though many persons who go to the Belasco these nights may never have seen the inside of a New York boarding house, there are few who will not have formed some sort of a mental picture of how a room in one of the old homes of fashion gone to seed would be likely to look under such conditions as are exploited in Mr. Klein’s play.

Over the mantel in the Houston Street room occupied by the struggling German musician, with whom New Yorkers are alternately laughing and crying these nights, you may happen to notice a spot on the wall where the kalsomining seems cleaner than elsewhere in the room. For a time you may wonder how it happened that in the general distribution of grime and grit this little cupola-shaped place escaped. The pawn ticket and the cuckoo clock allusion provide the explanation. That was the spot where the German’s treasured timepiece hung–before biting, nipping poverty, which so illy combines with artistic pride, forced him to make a visit to his “uncle,” a relative who in time of need and trouble makes no distinctions in birth or nationality, who is as ready to take interest in–or from–a German as an Englishman, an Irishman, or a native of the soil.

But pause to think about that little clean spot on the wall. Isn’t that going pretty far to get realism? Not one person in ten thousand would have thought of it. The obvious is readily apparent to any practical stage manager. But it is the little, elusive trifles like this that make perfection, that perfection which, from the copy books first, and from long trying since, we learned is no trifle. That bit of clean wall illustrates in an unmistakable way just why David Belasco is head and shoulders above other stage managers when it comes to realizing “atmosphere.”

[Eric: I cut a bit out here; these old-timey articles sure like to talk and talk without saying anything interesting. But I also wanted to point out how in 1904, the stage manager acted like our modern scenic designers. Also, the author uses the word “atmosphere” to describe our modern concept of “set dressing”. Back to the story.]

Before that last Sunday night rehearsal Belasco had used his biggest, broadest methods; and apparently not been satisfied with the result he now got down to fine and delicate details. Standing out in the empty, darkened auditorium he watched half a dozen men at work, every now and then tugging nervously at his gray front lock, moving from one seat to another, standing in the centre of the house, then down close to the footlights, or next far back in the gloom of the last seat in the topmost gallery.

One man on the stage was plying a great brush vigorously touching up the walls, the woodwork, and the furniture. That wall needed a bit more aging. The man applied his brush.

“No, No!” came from Belasco in a moment. “No more.” “It’s only water, Governor,” said the man with the brush. “It won’t change the color.”

“All right, then, go ahead. Don’t want to overdo it.” Then turning quickly to another of his assistants, “I want all that furniture polished; make it shine. We’ve got to make them see that Miss Houston is a good housekeeper. But those globes up there. Well, she’s too old to climb up there. They’re too clean. Take ’em down. They want to look as if they’d never been washed. Now mind, no paint on them. Get dirt, real dirt.”

Probably nine out of every ten people at the Belasco Theatre Monday night and since haven’t noticed a pile of old books lying in a shelf near the back of the stage. If they happened to notice them at all the chances are their eyes wandered aimlessly over the pile without taking any special note of the contents. Would they have done so if Belasco at that last rehearsal had not suddenly spotted an error like this:

“Thos books you’ve got in there”–this to the property man–”look like law books. Barwig wouldn’t give law books house room. Throw out those calfskin-covered things. Get some old Gartenlaubes. I want books there that suggest German literature. Got that down?”

The property man, who had been busy with his pencil, made a note, and Belasco was evidently satisfied with his promise to have the books on hand next morning.

Then came a funny bit of atmosphere hunting.

The old Houston Street house, once a home of wealth and fashion, boasts an old style chandelier, one of the kind with pendant crystal prisms, familiar to all of our grandfathers and to some of us. The chandelier used is the real thing, but Belasco from his point of view down in the orchestra chair suddenly observes:

“That chandelier is too well preserved. Remember there is a family of acrobats who do stunts and fall on the floor above. Even without the shaking they give it–well, it’s an old-timer, anyway! Here, let me have that.”

And in a twinkling he had snatched a hammer from the hand of a stage carpenter, mounted a small step ladder, and with a few deft strokes broken a prism here and there and sent a few of them whirling bodily to the floor.”

Then with a satisfied air he stood back and surveyed the result.

Are the rugs just the right color, or will a greener floor covering here or a dull yellow one there be better for the purpose? Is that coal scuttle just the thing, or will one a bit more old-fashioned be more in keeping with the set, at the same time in harmony with the general tone of the scenic picture–for a jarring note of color is often as bad as an actual anachronism. That fact is emphasized when the stage has finally been set for the second act revealing a Fifth Avenue interior in delicious greens.

“I want a bowl of flowers on that table,” says Belasco. In a few minutes the property man appears bearing a bunch of rich red roses. Belasco tugs at his curl and fidgets all over.

“No, no, no. That will never do. That red will send the whole thing awry. No brilliant red on the stage in this scene. Never. Never.”

The audience might not know why instead of listening to Mr. Warfield’s speeches its eyes were wandering up to a girl with a red rose on her corsage. But Belasco knows that red is a persuasive, compelling color that sometimes forces recognition when you don’t want to give it. American Beauties are used, but their color is not obtrusive.

Those are things that the master stage manager must know and think about. Those are the things that go to make perfection–things that are subtle, but oh, how potent in the mimic world! And the greatest stage manager is the one who has most feeling for just such seemingly little things which in the end create the semblance of reality and maintain it. And when a man after six or eight weeks of the most minute and detailed preparation, not to speak of months of closet study based on the results of years of labor and experience, still finds at the eleventh hour that there are a thousand and one little things that he can amend and improve, when no labor and no expense are too great to him to attain his end, he is pretty sure to get some results. When Belasco goes hunting for atmosphere he bags his game.