Here’s a behind-the-scenes look at the props in the 2010 version of True Grit. Property Master Keith Walters gives us a much more in-depth look at the research and process which goes on in developing the props than is normally found in these kinds of videos.

Tag Archives: process

Making a Fake Newspaper

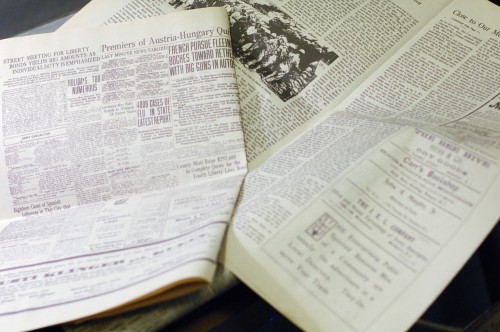

I found myself making a few fake newspapers this past year. One was for this summer’s All’s Well That Ends Well at Shakespeare in the Park. The director, Dan Sullivan, wanted Lafew to read a newspaper with the headline “King Lives” emblazoned on the front. The production was set in and around World War I.

Since they wanted tabloid-size papers (11″ by 17″), printing was no problem; I used 18″ by 24″ newsprint from those giant pads you can get and fed them through the manual feed tray of our large-format printer. It’s a pretty crappy printer for most things, but it’ll print newsprint with no problem. Anyway, once folded over, you just need to trim a little bit off each side to get it to the proper size.

The other tricky part of fake newspapers is getting all the content inside. Now, I’m not going to touch on the complexities of copyright here—if this were television or film, you would need to get clearances on all the material you put into your newspaper. In this case, the period of the newspaper I was creating meant I could use a lot of public domain text and imagery.

The first thing to do is research (obviously). You want to find out how big the text was, what kinds of fonts they used, what the covers looked like, how many columns were on a page, and all those sorts of things. You probably won’t find a single image of a newspaper that will solve all your demands that you can just print out, but you can probably find one that will serve as a guide for proportion and layout.

I’ve discovered a few sources that I like to use for locating old-timey newspaper articles. The first is the New York Times Archive. You can set an advanced search to just look through their papers from 1851-1980. The great part is that for the earliest papers (I think it’s anything before 1920-something) you can access a scanned image of the actual newspaper page. This means you can search for specific subjects or keywords and certain dates to populate your newspaper; if you look at the larger version of the picture above, you’ll see all the articles are about World War I. The difficult part is that you cannot browse the newspapers, so it can be a pretty rigorous process to click through each article to see whether it is the right size or “look” for your needs.

Another great source I’ve just recently come across is The Library of Congress’ “Chronicling America” archive of historic American newspapers. This site lets you browse and search a large number of newspapers from all across the country. The papers from 1836-1922 are fully digitized as well. Unlike the Times’ archive, you can view full pages, complete with the ads and artwork.

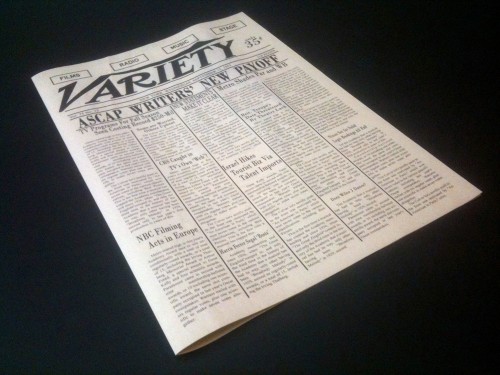

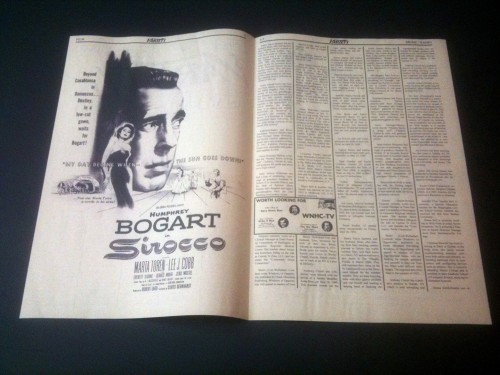

I like to do all my layout in Photoshop and keep the file until the show opens. That way, if the director or designer have a note, like enlarging a headline, I can just go back to the file, make the change, nudge everything else around to make it all fit, and print a fresh copy. In the above picture of “Variety” which I made for Compulsion, I had actor notes as well. Mandy Patinkin had to read and reference a real news article on the inside of the paper, so I had to make several variations on its size and placement before a final version was agreed to.

It can get pretty laborious to fill several pages with actual newspaper text, so I also searched for vintage ads to fill space. I also like to copy blocks of text and paste them onto other parts of the page; there’s no need for every word to be unique! In some cases where I couldn’t clean up smudges or distorted words, I actually retyped portions of the text with a closely-matching font.

Working with What you Have

It’s easy to think how hard it is to get started building props. Tools and machines are expensive, materials are hard to work with, and there are just so many to choose from. But think of this: the vast majority of materials we work with today were unavailable before World War II: all manner of plastics, all foams, all our composite materials, even our glues and paints. Nearly every kind of coating and adhesive has some form of synthetic polymer in it; before that, we had hide glue, wheat paste and rubber cement (well, after the 1900s that is). Even plywood as we know it was not something you could just go out and buy. It existed, but it was made by the carpenter himself, by laying up layer after layer of thin veneers.

For most of our theatrical history, props have been constructed with little more than papier-mâché, real wood, plaster, clay, leather, and natural fabrics. Animal glue and wheat paste were among the few adhesives available, and paints were limited to oil paints, casein, and varnishes. Think of all the theatre which was created and performed with this limited technology: everything from the Ancient Greeks, to Shakespeare and Molière, or Kabuki in Japan, up to the grand operas of the Gilded Age.

Think too of the tools we have available to us. Electricity and pneumatics have given us incredible power and speed in the palms of our hands. The industrial revolution and machine age have brought us standardized parts and precision unimaginable in previous times. Even our simple hand tools have benefited; a hand saw blade today is produced more quickly, cheaply, and precisely than before the industrial age. The steel it is made from is stronger and more consistent (and far less expensive).

From the weapons used by Alexander the Great to conquer the world, to the furniture found in Versailles, our museums are filled with amazing items created with nearly none of what our props artisans have available today. We can purchase a sheet of metal from a hobby shop which is superior in properties than the metal used by Genghis Khan to create his weapons which conquered the world. We can buy a Dremel tool for a pittance; imagine how envious the people who built the first railroads would be to see such a tool.

So if you are just starting out with prop making, or want to practice doing more of it, don’t wait until you can afford the fancy tools or can master the most modern materials. Think about what you can do with what you have, rather than what you can’t with what you don’t.

Stuck in the Middle

The beginning of your process in building a prop can take awhile with no apparent progress. First, you have a lot of research to get the look and design figured out. You may need to make construction drawings, sketches, or even full-scale layouts. Choosing your materials, deciding on techniques and planning the order of tasks can also take some time. Depending on the type of prop you are building you may need to generate cut lists, construct jigs and templates or draw up patterns. Even just gathering or ordering your materials and parts can take up time. In other words, you can spend hours or even days upon starting a project before the prop itself begins to take shape.

In a similar vein, the end of the process can be a slow ordeal. Filling and sanding, coating and painting, or whatever your finishing touches are usually take a lot more time than you anticipate. I’ve found for projects which require a smooth or pristine finish, the sanding and smoothing part can take longer than the construction of the prop itself. Anyone who has painted can also attest that the preparation of the surface and masking out of areas is the longest part of the process; the actual application of paint is but a blip in the overall time frame of the process. Like the beginning of the process, the end can take a significantly longer amount of time than the construction of the prop.

It is usually the middle which takes the fastest. You spend a few days planning the prop out, than in one afternoon, all the pieces go together like magic. Then it takes another few days to get it to a finished state. It is this middle phase where progress on the prop is the most visual, that is, when it seems you are working the fastest. But a quick construction period can only happen with thorough planning, and a well-made prop can only result from thorough finishing.

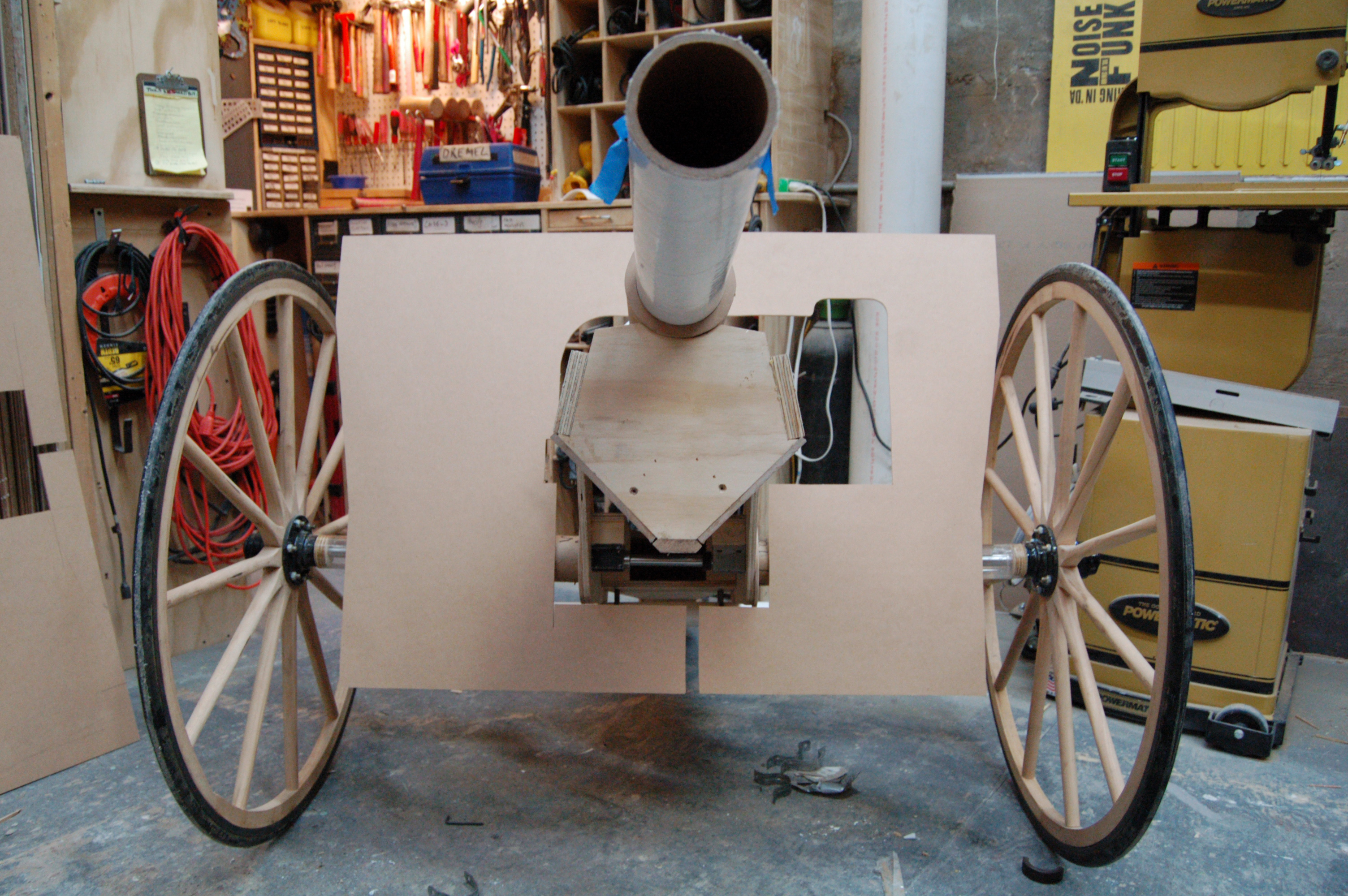

A New Prop for Shakespeare in the Park

Here’s a quick sneak preview of one of the props I am building for one of the shows in this summer’s Shakespeare in the Park.

Try to guess what it is before looking though all the pictures. Continue reading A New Prop for Shakespeare in the Park