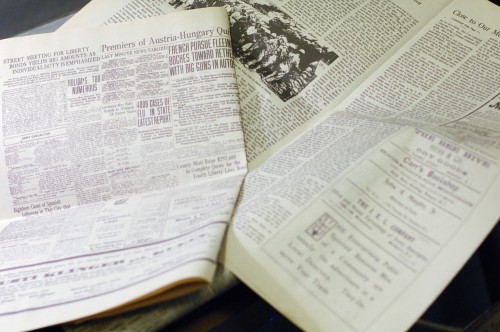

I found myself making a few fake newspapers this past year. One was for this summer’s All’s Well That Ends Well at Shakespeare in the Park. The director, Dan Sullivan, wanted Lafew to read a newspaper with the headline “King Lives” emblazoned on the front. The production was set in and around World War I.

Since they wanted tabloid-size papers (11″ by 17″), printing was no problem; I used 18″ by 24″ newsprint from those giant pads you can get and fed them through the manual feed tray of our large-format printer. It’s a pretty crappy printer for most things, but it’ll print newsprint with no problem. Anyway, once folded over, you just need to trim a little bit off each side to get it to the proper size.

The other tricky part of fake newspapers is getting all the content inside. Now, I’m not going to touch on the complexities of copyright here—if this were television or film, you would need to get clearances on all the material you put into your newspaper. In this case, the period of the newspaper I was creating meant I could use a lot of public domain text and imagery.

The first thing to do is research (obviously). You want to find out how big the text was, what kinds of fonts they used, what the covers looked like, how many columns were on a page, and all those sorts of things. You probably won’t find a single image of a newspaper that will solve all your demands that you can just print out, but you can probably find one that will serve as a guide for proportion and layout.

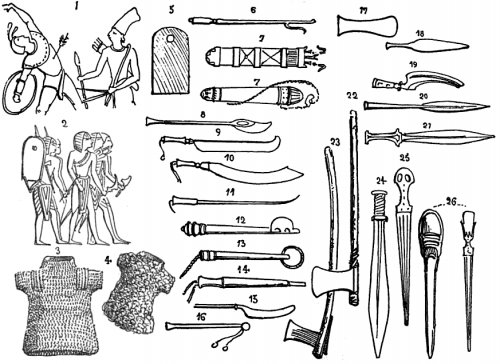

I’ve discovered a few sources that I like to use for locating old-timey newspaper articles. The first is the New York Times Archive. You can set an advanced search to just look through their papers from 1851-1980. The great part is that for the earliest papers (I think it’s anything before 1920-something) you can access a scanned image of the actual newspaper page. This means you can search for specific subjects or keywords and certain dates to populate your newspaper; if you look at the larger version of the picture above, you’ll see all the articles are about World War I. The difficult part is that you cannot browse the newspapers, so it can be a pretty rigorous process to click through each article to see whether it is the right size or “look” for your needs.

Another great source I’ve just recently come across is The Library of Congress’ “Chronicling America” archive of historic American newspapers. This site lets you browse and search a large number of newspapers from all across the country. The papers from 1836-1922 are fully digitized as well. Unlike the Times’ archive, you can view full pages, complete with the ads and artwork.

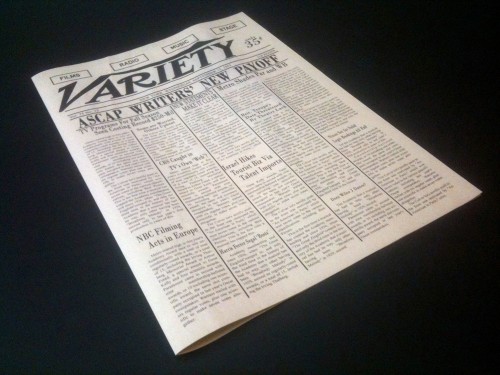

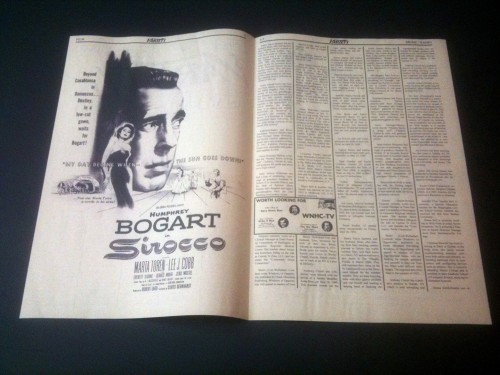

I like to do all my layout in Photoshop and keep the file until the show opens. That way, if the director or designer have a note, like enlarging a headline, I can just go back to the file, make the change, nudge everything else around to make it all fit, and print a fresh copy. In the above picture of “Variety” which I made for Compulsion, I had actor notes as well. Mandy Patinkin had to read and reference a real news article on the inside of the paper, so I had to make several variations on its size and placement before a final version was agreed to.

It can get pretty laborious to fill several pages with actual newspaper text, so I also searched for vintage ads to fill space. I also like to copy blocks of text and paste them onto other parts of the page; there’s no need for every word to be unique! In some cases where I couldn’t clean up smudges or distorted words, I actually retyped portions of the text with a closely-matching font.