Originally appeared in an 1899 issue of New York Times:

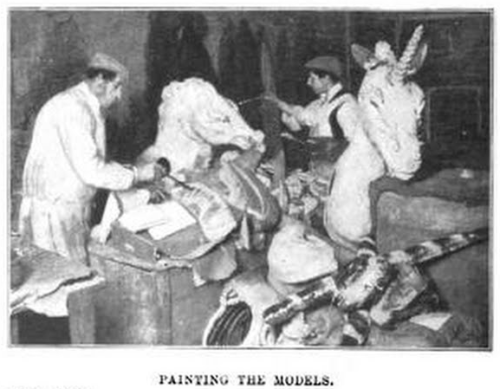

“Yes,” said the little man up town who makes theatrical “Props” and incidentally any number of “props” for other things, “there is nothing like papier maché. It is being used more and more all the time now and there are more and more things for which it can be used. It is the strongest material known for its weight. You see, for anything to use in the theatre you have to have something that is strong and that will stand traveling and being thrown around, and if it is big—columns in the scenery, for instance—it must not only be strong but light, so that it can be moved easily. It must be light anyway. Imagine a band of Amazons traveling around the country with suits of metal armor, or wearing it, either, for that matter. The Amazons would strike, the railroad companies would strike, and the theatrical company would go out of business. There is nothing you can’t make of papier maché, from an elephant to a vase. The greatest trouble is to get the models. Sometimes you send out and get small ones of plaster or marble, and at other times you will have to work from sketches and photographs and use your own ingenuity, working on a geometrical scale for enlargement. Continue reading The Art of Papier Mache, 1899