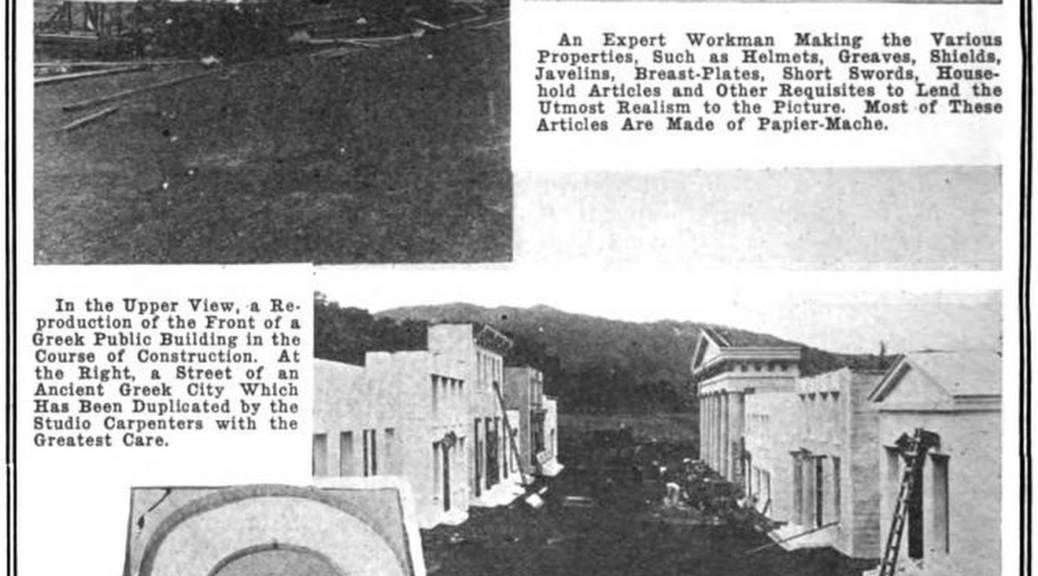

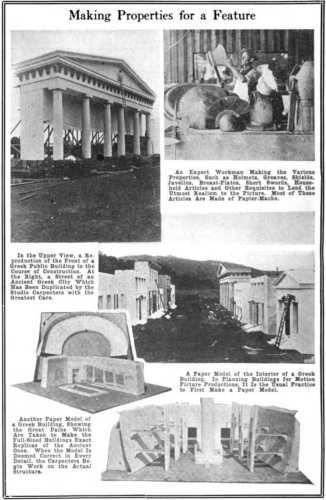

The following instructions for creating props from paper-mache comes from a 1905 book, but the techniques remain virtually unchanged over a hundred years later:

Papier-mâché, as its name proclaims, is of French origin. Good examples are still to be found in many French buildings of the sixteenth century. The grand trophies and heraldic devices in the Hall of the Council of Henri II. in the Louvre, as well as the decorations at St Germain and the Hotel des Fermes, on their ceilings and walls, are executed in papier-mâché. In 1730 a church built entirely of papier-mâché was erected at Hoop, near Bergen, in Norway…

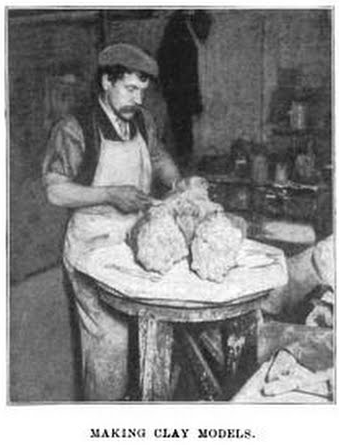

Papier-mâché Stage Properties.—Modellers and plasterers often find employment in the property rooms of theatres in modelling, moulding, and making masks, heads of animals (the bodies are made of wicker work), and architectural decorations for solid or built scenes. Papier-mâché properties are produced from plaster piece moulds. Large sheets of brown and blue sugar paper are pasted on both sides, then folded up to allow the paste to thoroughly soak in. The first part of the paper process is known as a “water coat.” This is sugar paper soaked in water and torn in small pieces and laid all over the face of the mould, to prevent the actual paper work from adhering. The brown paper is then torn into pieces about 2 inches square, and laid over the water coat, and coats of sugar paper are laid in succession in a similar way until of sufficient thickness to ensure the requisite strength. The various pieces of paper are laid with the joints overlapped. Care must be taken that each coat of paper is well pressed and rubbed into the crevices with the fingers, and a brush, cloth, or sponge, so as to work out the air and obtain perfect cohesion between each layer of paper, and form a correct impress of the mould. After being dried before a fire, the paper cast is taken out of the mould, trimmed up, and painted. A clever man can, by the use of different colours and a little hair, give quite a different appearance to a mask, so that several, taken out of the same mould, will each look quite different. The use of different coloured papers enables any part of the previous coat that may not be covered to be seen and made good. Some property men do not use a water coat, but dry the mould, and then oil or dust the surface with French chalk to prevent the cast sticking to the mould. Others simply paste one side only of the sugar paper that is used for the first coat…

Paste is made with flour and cold water well worked together, then boiling water is poured on, and the mass well stirred.