Props people are often said to “have a good eye” when it comes to building furniture or dressing a set. Well, if you don’t wear safety goggles when working in the props shop, you may end up with NO EYES AT ALL.

Safety goggles are often thought of in two different ways; there are impact resistant goggles and chemical splash goggles.

When you are woodworking, grinding metal, even hammering, you are creating the risk that a piece of material will fly into your eyes. Impact resistant goggles will protect your eyes from all but the most severe projectiles; if you are working on something that can break through a pair of impact resistant goggles, it can probably also break through your skin and or bones, in which case, you need more than just eye protection. Specifically, OSHA sets the minimum standard which impact resistant goggles must meet to ANSI Z87.1. You can read a summary of ANSI Z87.1 to see what kind of tests they perform on goggles.

For chemical splash goggles, most labs also recommend goggles which conform to ANSI Z87.1 as a minimum. Additional recommendations include goggles which wrap around the sides to fit snugly against the face. Elastic bands keep the goggles tight against the face and resist being knocked off from side impacts. Vents on the side help the eyes breathe and keep the goggles from fogging, but they should be designed in a way so that chemicals splashing from the front can’t get inside.

You can, of course, find goggles which claim to be chemical splash goggles but offer no impact resistance whatsoever. These will keep your eyes dry but little other protection. Since you should have ANSI-rated goggles for both impact and chemical protection, these kinds of goggles are completely worthless and should be avoided at all costs.

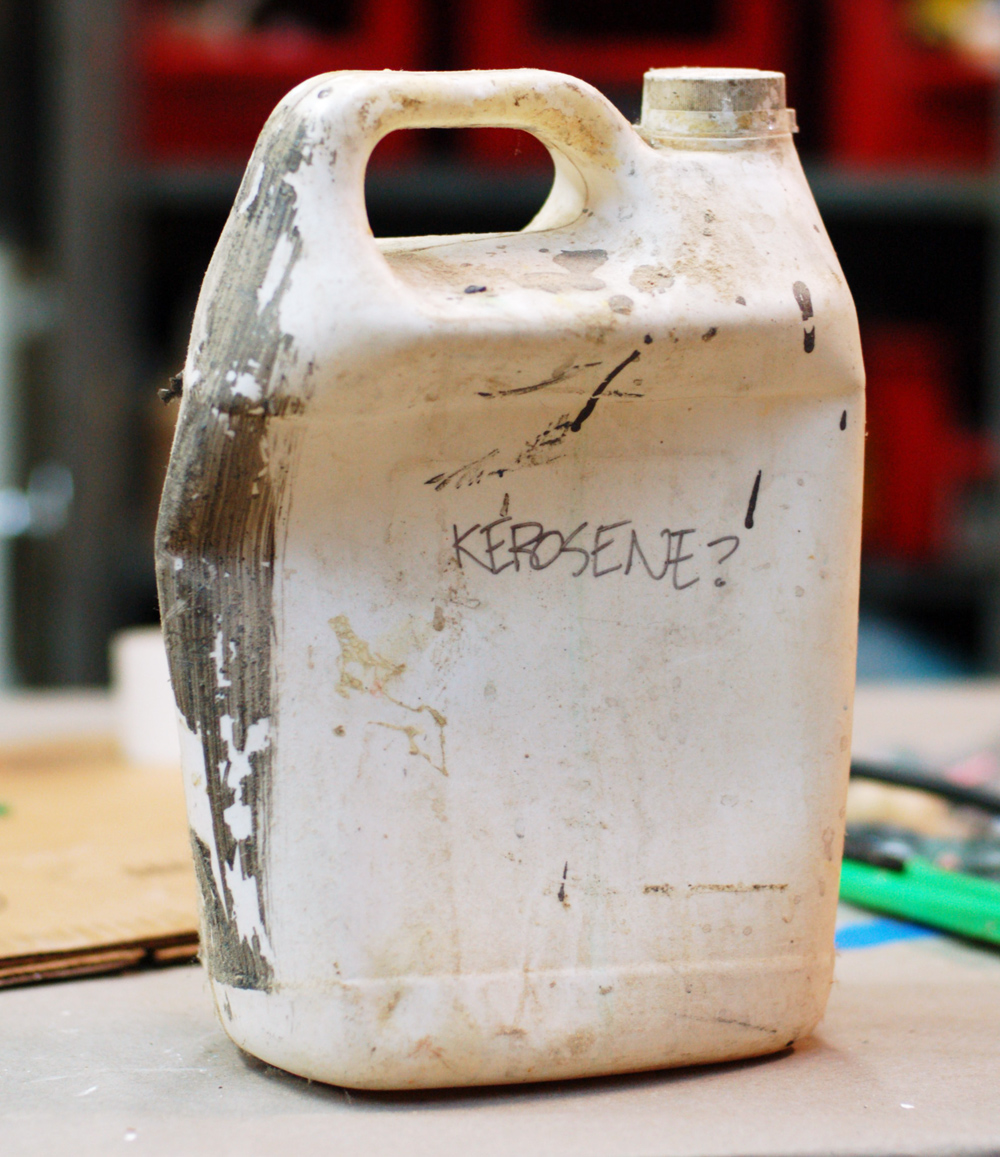

Working in props can demand both types of goggles. Carpentry, metal-working and other “hard materials” projects require impact resistant goggles. Working with epoxies, resins, powders, paints and other chemicals, as well as with heat and glassware, require chemical splash goggles. You can, of course, find a single pair of goggles which fills both needs, or you can have two pairs of goggles. Either way, you do not want to use goggles which fit neither needs. Often, you can find yourself working in a prop shop where a couple pairs of goggles are found thrown in a bin, with no indication of whether they conform to safety standards, not to mention how unhygienic this is. If you can’t identify the brand and model of a pair of goggles, then you can’t know whether it conforms to safe standards, and you have to assume it does not.

I recommend having your own personal set of goggles. Besides working in shops with a poor selection of safety equipment, you may also find yourself working in places which aren’t actually shops. Technically, your employer is supposed to provide you with the safety equipment you need, but like most props artisans, you may do a fair amount of work on your own, either as a hobby or to make extra cash. A personal pair of goggles also means you can find a pair that fits well and that feels well; you should not forgo eye protection just because most goggles feel uncomfortable on your face. You have a multitude of choices in eyewear out there, most under $20. Even the most expensive pairs are only $80-90, which is still far less than the cost of a visit to the eye doctor, not to mention the lifetime cost of losing an eye. Mind you, the price of goggles is not necessarily an indication of their quality or effectiveness.