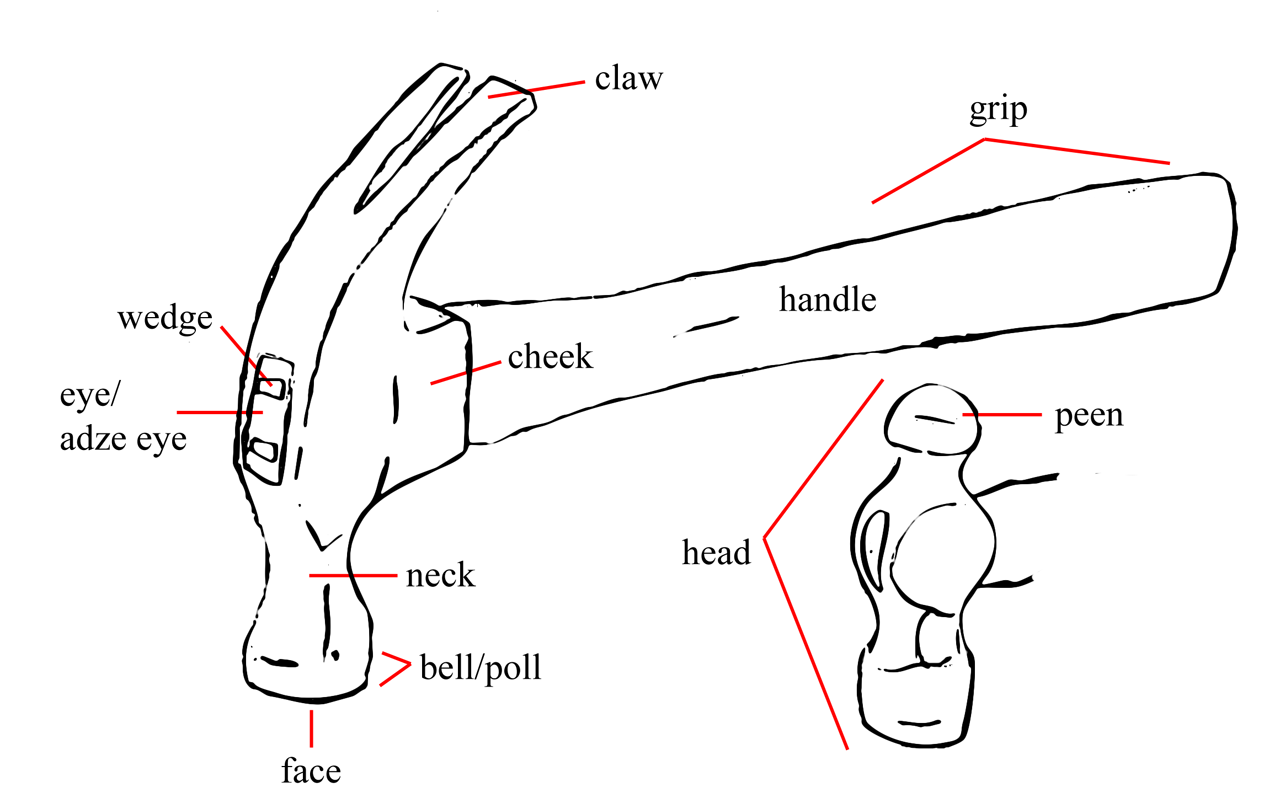

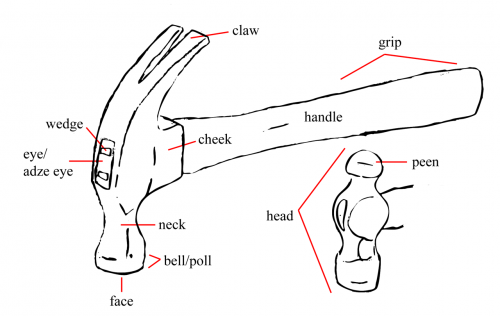

Your basic hammer is made of two parts: the handle and the head. The handle fits through a hole in the head known as the eye (or adze eye), and is held in place with a wedge. On newer hammers, the grip may be wrapped in rubber for greater comfort. The face is what strikes the nail or other surface you are hammering. Hammers used for peening, or shaping metal come in a number of varieties. A ball peen hammer has a peen with a hemisphere shape. A claw hammer has a claw used for removing nails or separating two pieces of wood.

I gathered some of the hammers we have in our shop, which represent some of the more common types which are useful to the props artisan. From left to right, we have:

Claw hammer: Your basic carpentry hammer is useful for driving and removing nails into wood. It’s also the go-to-hammer for basic “hitting stuff”; I kind of cringe every time I see someone grab a ball peen hammer to knock something loose.

Rawhide mallet: Useful for non-marring blows, especially when working with leather, jewelery or other softer and delicate metals.

Lead mallet: These are used to hit steel without the risk of creating sparks. You can also get copper mallets for the same purpose.

Soft-faced hammer: The faces are made of soft materials, such as rubber or plastic, and are often removable and replaceable. These are used when you are hammering on or around decorative or finished wood to keep from marring the surface.

Tack hammer: Used in upholstery to drive tacks. One end is split and often magnetic to help hold the tiny tacks while driving them in.

Ball peen hammer: Peen hammers are used for shaping metal. Besides the ball peen, you may also find straight peen, cross peen, and point peen, among others.

Wooden mallet: Or carpenter’s mallet, used for furniture assembly or driving in dowels when non-marring blows are needed.

You can of course find any number of other types of hammers and mallets, with many variations in between. Prop shops will often carry rubber mallets, rip hammers and sledge hammers. Other types of hammers, such as bricklayer hammers or drywall hammers may also find their way into shops. Check out the Science and Engineering Encyclopedia for a comprehensive list of hammers.