In previous posts, I showed off some foam cannon barrels I built and some giant champagne bottles I helped work on for the Santa Fe Opera. I also built the four carriages they rode around on.

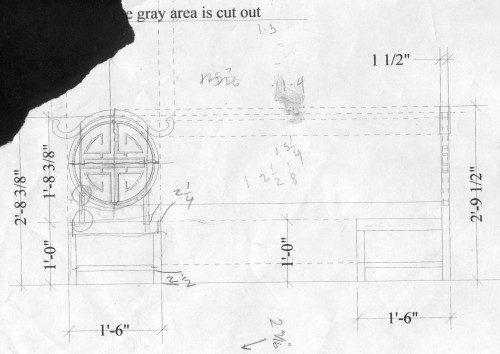

The main beams of the bases were cut out of plywood. I drew out a full-scale pattern for one of them and cut it out, then transferred it to all the pieces of plywood and cut those out to match. The bottom needed a square notch to hold the axle assembly, and it needed to be in the exact same location on all the pieces so the wheels would sit straight, so I attached all the pieces together and cut the notch out on all of them at once.

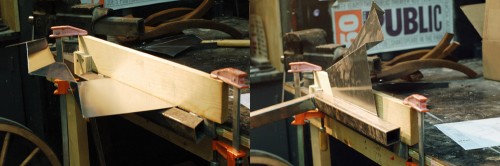

Next I built a jig to hold the beams. They sat at an angle and tapered out at the top. While in place, I measured and cut the cross pieces to fit exactly. This part took awhile to get perfectly correct, but once I had the pieces for one of them, I could just duplicate them for the other three carriages.

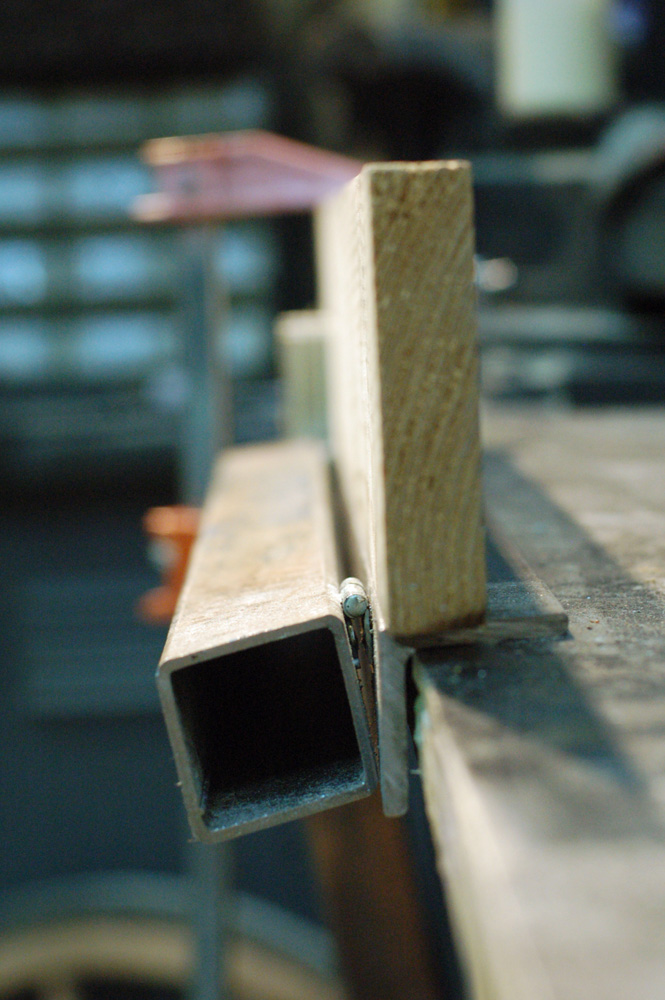

The carriages wanted to look like cast iron, so I faced all the edges with some strips of wood that were a little wider than the bases and rounded over on the ends. This gave it that look you might find on I-beams or similar pieces of metal. The photograph above shows a trick I read about that I wanted to try out: clamping a long strip of wood using rubber bands and spring clamps. It was not as effortless as I thought it would be, but it was a better clamping method than anything else I’ve used in the past.

With the major structure in place, I began adding details, like bolt heads and plates. These were all applied pieces; I cut and shaped the larger bolt heads out of MDF, while the smaller bolt heads were just short lag bolts that I screwed in.

The wheels we used were bought from a place that makes wooden carriage wheels; I’ve made wheels in the past, but it’s very time-consuming, and hard to make them as strong as a legit wooden wheel. I attached a pipe to each of the wheels as an axle, and found a slightly larger pipe that could sleeve over them. I welded this larger pipe to some plates so I could bolt it to the carriage. In the photo above, you can see the axle pipe is in two sections. When building a carriage like this, you need the wheels to be able to spin independently of each other, because when you make turns, they spin at different speeds. The long aluminum pipe going through both larger pipes in the photograph was used to line them up with each other while attaching them.

The whole thing got a pretty interesting paint treatment by the paint crew. Overall, it was a very fun project that saw a lot of stage time during the performance. It was also interesting to compare it to the previous cannon I have built, which could not be more different than this one both in appearance and in methods of construction.