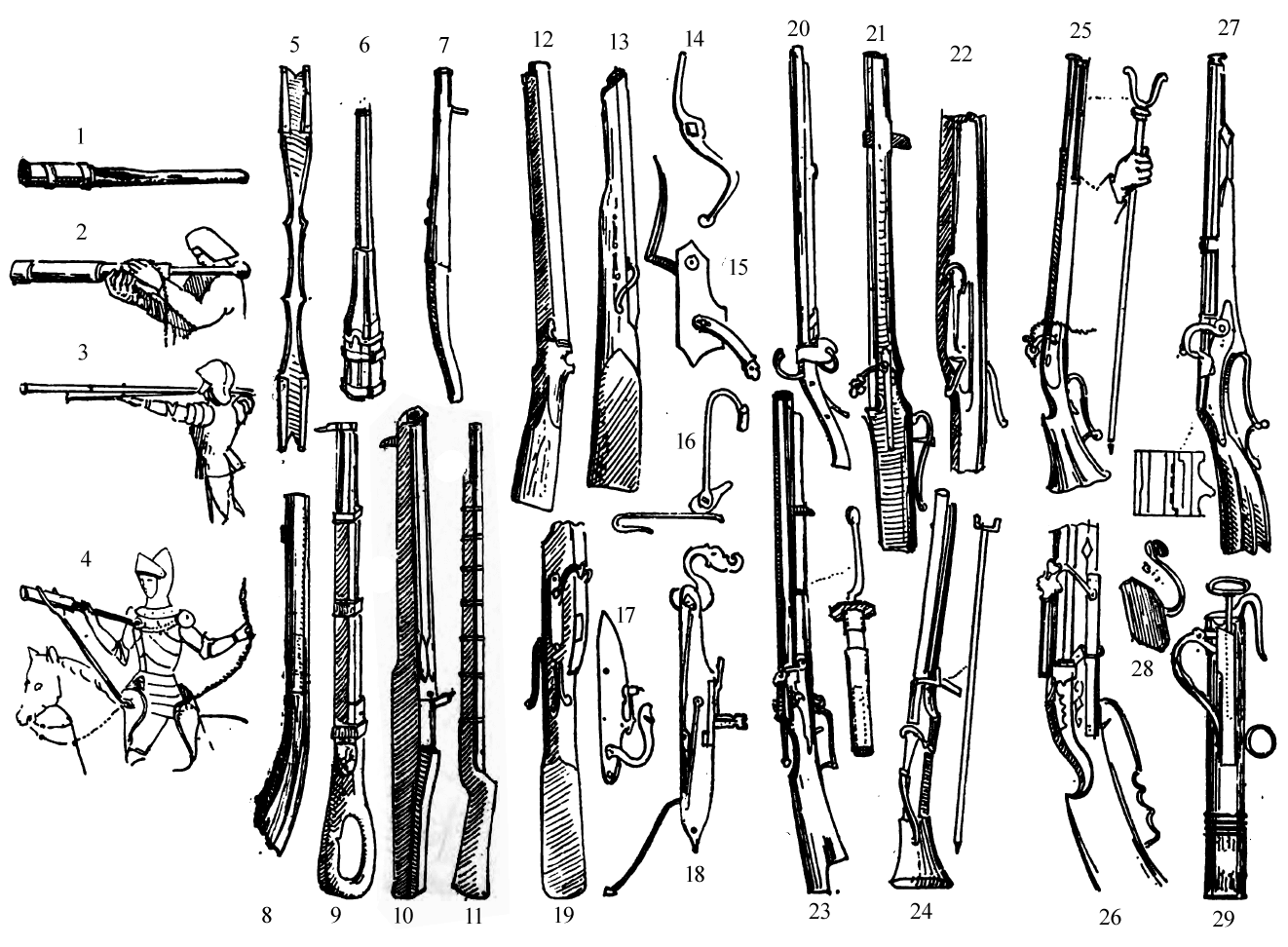

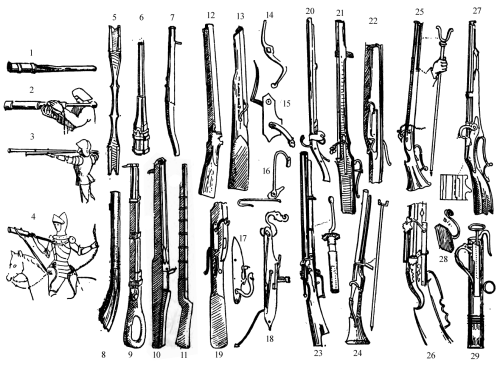

- Hand cannon for foot soldier in cast iron, belonging to the first half of the fourteenth century. The touch-hole (German, Zünderloch) is on the upper part of the cannon.

- Hand cannon for foot soldier, from a MS. of the end of the fourteenth century. The touch-hole is on the top of the cannon.

- Hand cannon for foot soldier, from a manuscript of the year 1472, in the library of Hauslaub at Vienna.

- Hand cannon for a knight, called a petronel, from a manuscript in the ancient library of Burgundy. The articulated plate armour is characteristic of the latter half of the fifteenth century, though the bassinet has a movable vizor. These hand cannons were in use at the same time as the serpentine arquebuse, and even as the flint and steel arquebuses and muskets, ie till the beginning of the sixteenth century, as may be seen from the drawings, by Glockenthon, of the arms of the Emperor Maximilian I. (1505).

- German hand cannon, fixed on wooden boards or stands, belonging to the beginning of the sixteenth century. The touch-hole is still on the upper part of the cannon. From the drawings of Glockenthon, done in 1505.

- German hand cannon in fluted iron, of the beginning of the sixteenth century, or end of the fifteenth century. It is only 9 1/2 inches in length, 2 inches in diameter, and is fixed on to a piece of oak about 5 feet in length. In the Germanic Museum, where it is wrongly ascribed to the fourteenth century.

- Hand cannon in wrought iron, called a petronel, to be used by a knight. It is of the end of the fifteenth century.

- Hand cannon with stock of the end of the fourteenth century. The touch-hole is on the top of the cannon.

- Angular hand cannon on stock; to be used in defending ramparts. It is a little over 6 feet in length, and the touch-hole is on the top of the cannon. This piece was used in the defence of Morat against Charles le Téméraire (1479).

- Eight-sided hand cannon with stock. The touch-hole, which is on the top of the cannon, has a cover moving on a pivot. This cannon is 54 inches in length, and the balls or bullets about 1 1/2 inch in diameter. It belongs to the first part of the fifteenth century.

- Persian matchlock cannon, copied from the Schah-Namen, in the Library of Munich.

- Hand cannon on stock, end of the fourteenth, or beginning of the fifteenth century. In this piece the touch-hold is on the right side.

- Hand cannon with serpentine, a match-holder, without trigger or spring, invented about the year 1424.

- Serpentine or guncock for match, without trigger or spring.

- Serpentine without trigger, but with spring.

- Serpentine with spring, but without trigger.

- Serpentine lock, without trigger or spring.

- Hackbuss lock with spring and trigger.

- Hackbuss (in German, Hakenbüchse) or hand cannon, with butt end and serpentine lock. It belongs to the second half of the fifteenth century. The match is no longer loose, but fixed to the serpentine, which springs back by means of the trigger. This sort of cannon is generally about 40 inches in length, and it is usually provided with a hook, so that when it is placed on a wall it cannot slip back. The hackbuss without a hook is, as a rule, better made, and was subsequently called arquebuse with matchlock. It had also front and back sights (in German, Visir und Kern).

- Chinese arquebuse.

- Swiss arquebuse of the second half of the fifteenth century.

- Double arquebuse (in German, Doppelhaken). This weapon had two serpentines, or dogheads, falling from opposite points, and was generally used in defending ramparts; the barrel was usually from 5 to 6 1/2 feet in length.

- Hackbuss, loaded from the breech by means of a revolving chamber, a weapon belonging to the beginning of the sixteenth century.

- Hackbuss and gun fork (German, Gabel), from the drawings of Glockenthon; it may also be seen in the engraving of the “Triumph of the Emperor Maximilian I.” From this we see that the hackbuss, or match arquebuse, was used for a long time together with the wheel-lock arquebuse.

- Serpentine hackbuss with match, also called musket. It is also furnished with a fork, called a fourquine in French.

- Hackbuss or musket, with link.

- Serpentine hackbuss with link, also called arquebuse, loaded from the breech by means of a revolving chamber. It dates from the year 1537, and bears the initials W. H. by the side of a fleur-de-lys.

- Eye protector, belonging to a musket in the Arsenal of Geneva.

- Hand cannon with rasp, early part of the sixteenth century. It is entirely of iron, and is called Münchsbüchse (monk’s arquebuse). For a very long time it was wrongly thought to be the first fire-arm ever made, and to have belonged to a monk named Berthold Schwartz (1290-1320), who was also said to have invented gunpowder. This little weapon is about 11 1/2 inches in length, and the barrel 5 inches in diameter. It preceded the wheel-lock, and appears to have suggested the idea of it. A rasp scatters sparks from the sulphurous pyrites by friction.

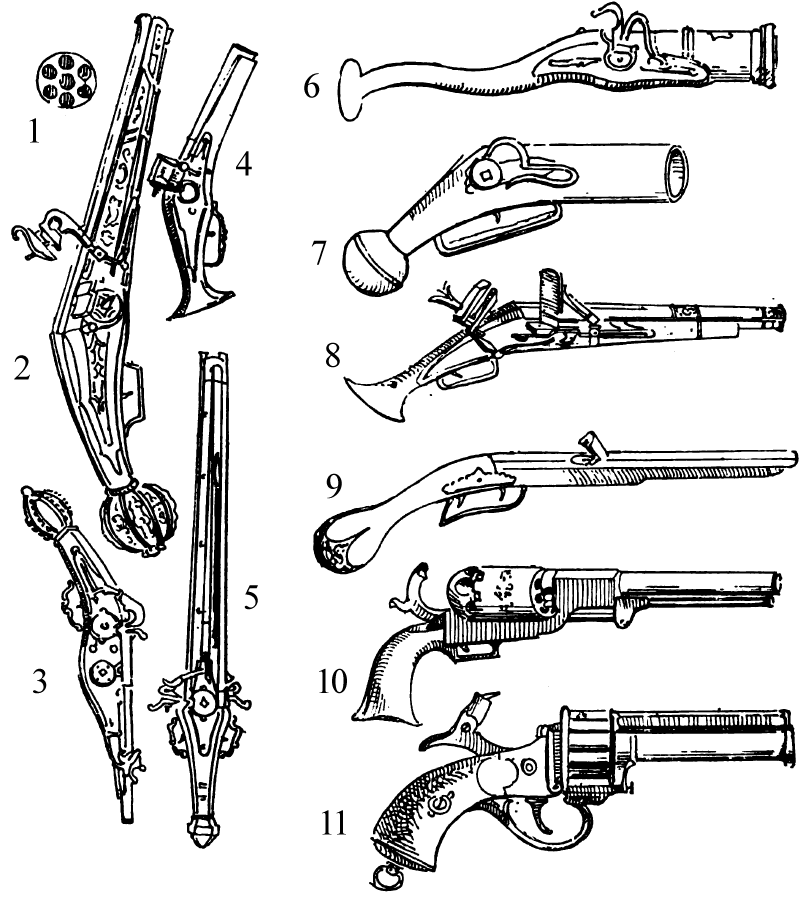

The illustrations and descriptions have been taken from An Illustrated History of Arms and Armour: From the Earliest Period to the Present Time, by Auguste Demmin, and translated by Charles Christopher Black. Published in 1894 by George Bell.