When I say “the first property maker”, I mean in terms of a professional person who earns a living making props. People have made props throughout history in many theatrical traditions; they certainly haven’t appeared from nowhere. Many traditions probably sustained quite a class of artisans devoted to the theater, particularly in Ancient Greece and Rome. Certainly too, there are many forms of theatre outside of our Western traditions. What I am looking at is the first group of people known as “property makers” who could make a living building props for professional theater. For that, we must look to the origins of what, in many ways, has become our idea of modern theatre and performing arts, the Elizabethans.

The pinnacle of Tudor, Elizabethan and Jacobean theatre centered around the monarchy, which hired many types of artists to perform at Court, festivals and pageants, and licensed other forms of entertainment throughout the city. Though various officers were tasked with this job earlier, the first official “Master of the Revels” with an independent office was Sir Thomas Cawarden in 1544. The office and storage facilities were consolidated to a dissolved Dominican monastery at Blackfriars. Cawarden was known for his skill in taking sketches and turning them into fully-realized productions. This required a whole “production team”, as well as the ability to communicate the needs of the stage to a group of skilled craftsmen who understood the special considerations which theatre requires. After Cawarden’s death in 1559, the office moved to the priory of St. John of Jerusalem in Clerkenwell.

The office moved several times throughout its history; in 1608, it came to be located in the Whitefriars district outside the western city wall of London. The Master of Revels at the time, Edmund Tilney, described that the Office:

…consisteth of a wardrobe and other several [i.e. separate] rooms for artificers to work in (viz. tailors, embroiderers, property makers, painters, wire-drawers and carpenters), together with a convenient place for the rehearsals and setting forth of plays and other shows….”

[Halliday, F. E. A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964. Baltimore, Penguin, (1964)]

Tilney also noted that the office served as a residence for the Master and his family, as well as other personnel.

The records kept by the Office of the Revels informs much of what we know about the artisans hired to furnish the theatre with its physical “stuff” and the money spent on materials. It was not just writers and actors who were beginning to develop into a new profession at this time, but a whole range of carpenters, tailors, plasterers, wiredrawers, painters, plumbers and others who were becoming a new “theatrical artisan” class. Some of these artisans appear in the records steadily employed for periods of thirty or even forty years.

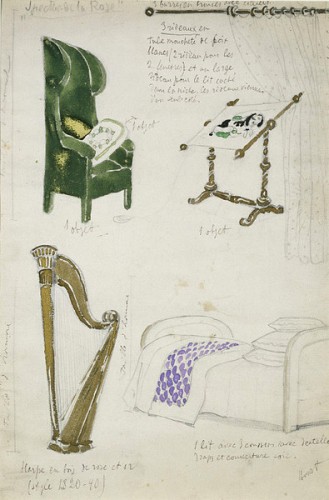

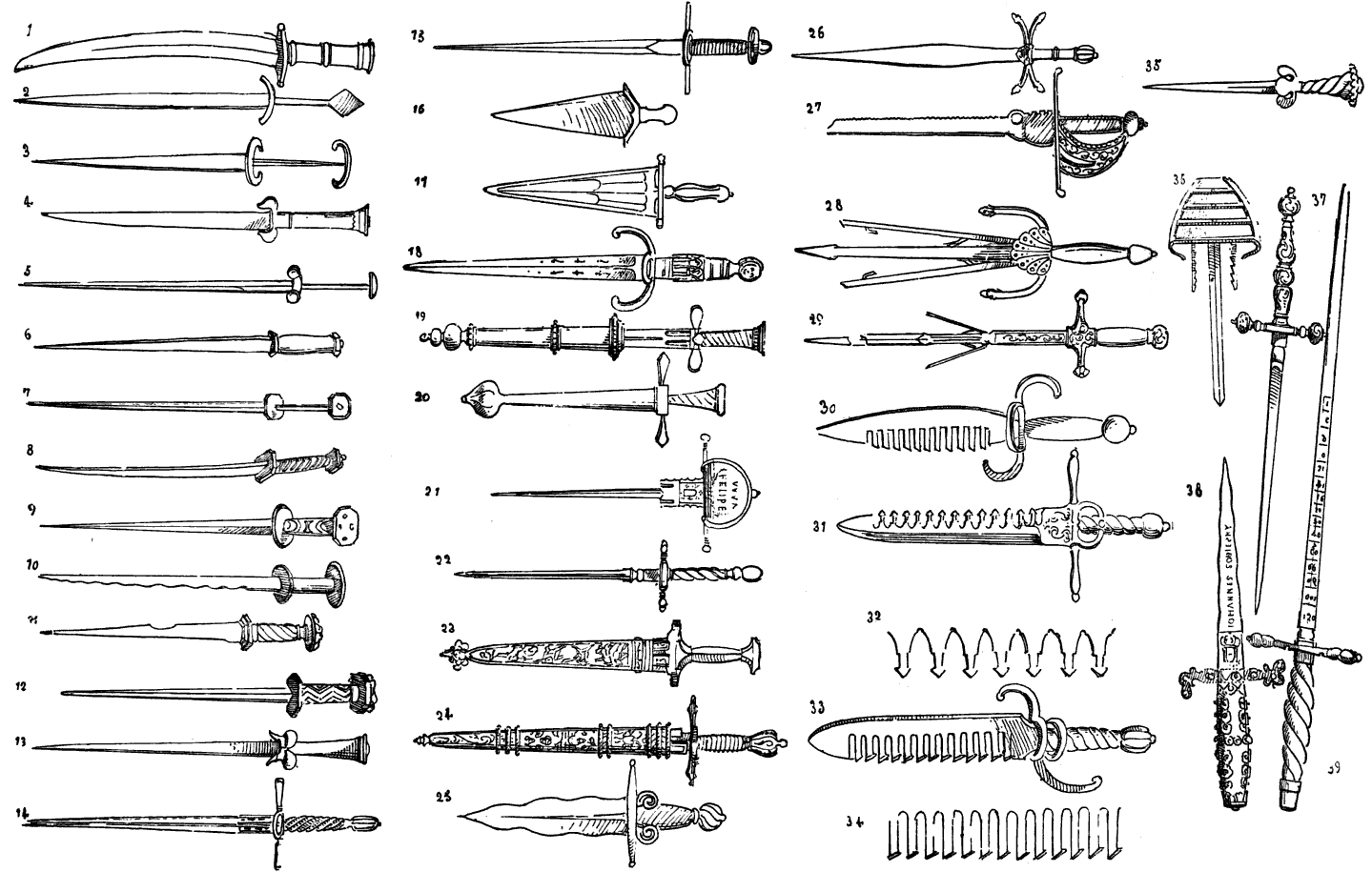

One of the first artists to be listed in the Revels records as a “property maker” is a man named John Carowe (or Carow or Caro). He was first employed in 1547 for the coronation of Edward, and continued to work as a property maker, joiner and carver until his death in 1574. In these records, “property making refers” not just to hand props like heads and swords, but also to the custom construction of stage furniture and large scenic devices (such as wagons and hell-mouths). In this account of expenses paid between December 1573 and January 1574, we see some of the things Carowe has provided to the Revels:

John Caro, Property maker, for money to him due for sundry parcells Holly and Jug for the play of Predor.–Fishes counterfet for the same, viz Whiting, Place, Mackarell, &c.–A payle for the castell top–Bayes for sundry purposes,–Lathes for the hollo tree–Hoopes for tharbor and top of an howse,–A truncheon for the Dictator,–Paste and paper for the Dragons head,–Deale boordes for the Senat Howse,–A long staf to reach up and downe the lights,–Fawchins for Farrants play–Pynnes styf and greate for paynted clothes,–Formes ii. and stooles xii, &c.–In all lxixs. ixd [69 shillings, 9 pence].

Carowe was also in charge of overseeing other property makers, as we can see in this account of the 1572 Christmas Revels, separated into individual projects:

Propertymakers: Iohn Caro, Iohn Rosse, Nicholas Rosse, Iohn Rosse Iunior, Thomas Sturley, Iohn Ogle, Iohn David for Caro.

Propertymakers, Embroiderers, and Haberdashers: Iohn Caro, William Pilkington, Iohn Sharpe, Iohn ffarington, Iohn Tuke, Iohn Owgle, Iohn David for Caro, Ione Pilkington

Propertymakers, Embroiderers, and Haberdashers: Iolin Carowe, William Pilkington, Iohn ffarrington, Iohn Tuke, Ione Pilkington, Thomas Tysant, Iohn David for Caro.

You can see one of the property makers is named John Rosse, and another John Rosse Junior; like many crafts at this time, the evidence points to fathers passing their skills along to sons to keep the theatrical traditions alive. It would seem that Carowe made some of his props in his own shop, which must have been thriving, while others were constructed in the Revels Offices mentioned at the beginning.