It’s hard to believe this blog has been running for another year already. Last year, I summed up the first 162 posts. I’m doing the same thing again this year. If you are new to this site, or even if you’ve been checking it out for awhile, you may not know how much stuff is here; I’ve written 313 posts (that’s over 139,000 words). You can subscribe to my blog with your favorite blog reader, or sign up to get all articles through email so you don’t miss anything in the future. I add three posts a week, and as a bonus, the RSS feed and email subscriptions remain advertisement-free. I also have a Twitter feed where I share news and links about props. If you’ve been reading this blog for awhile, now would be a great time to leave a comment or drop an email if you haven’t yet; and if you have, feel free to leave another.

I had some things going on outside of this blog this past year. Back in September, I was interviewed at TheatreFace, and you can read the transcript at the site. I also had an article in Stage Directions magazine on the breakable phone from The Book of Grace; another article will be appearing in this February’s issue.

I really hit a nerve with the props community when I asked Why is there no Tony Award for Props? My article On sharing and secret knowledge also proved popular. 25 memorable film props was a big hit with the kids. Other feature length articles I’ve written include Challenges in making props lists for Shakespeare, Which classes should I take, Importance of photographing your work, How much should you charge for your work?, A Common Error in Making Cutlists, Buying the Right Tools, Using soft materials to mimic hard details, Building a Prop from a Photograph, applying for a NYC Theatrical Weapons Permit, and the all-important question: Why Make? I shared Some thoughts on brand-name props, Thoughts on green props, and Thoughts on 3D Printing Technology. I shared two shorter pieces On making things and Getting the shape you want,, and finally gave advice on what to do When Nothing is Happening.

I am interested in the definitions of props and the ideas behind what it means to work in props, and so I opined on what the difference is with a prop master vs prop director, how to tell whether something is a Prop or Not? and what it means when a prop is Cut! I also asked Why the term prop master?, gave my theories on the Confusions in the definition of a prop, and listed some Categories of props.

I showed some process shots from some of the projects I and others in the shop have worked on, such as faux oil paintings, a fake deer butt, a paper-tearing jig, fake french fries, a breakaway telephone, a Medusa head, an LED lighter, a fake dead lamb (part one, part two, and three), a steel headboard for In the Wake, a stuffed kitten from recycled fabric, a chandelier from Romeo and Juliet, as well as an overview of the props from The Book of Grace, and the paper props from Capeman. I also documented the process in making a blood sponge bag, how to gold leaf, faking a beer can, making a switchblade, five quick prop fixes, and ways to make crack and snow.

I took a heavier focus on safety this year, with articles on E-cigarettes, choosing the right disposable glove, all the chemicals in the world, blank-firing guns, and “A Label of Love“.

This past year saw “Props Month” at Stage Directions magazine, as well as the launching of the new S*P*A*M website. I attended the S*P*A*M conference in San Francisco, where I also got to take tours of the San Francisco Opera and the Berkeley Repertory Theatre prop shop. I also attended the  Maker Faire 2010, 2010 NYC Props Summit, and the Going Green in Theatrical Design: Set & Props Workshop sponsored by the Broadway Green Alliance.

I began offering reviews of books for props people, and started off with some of the most commonly used texts, including Theatrical Design and Production by Gillette, Careers in Technical Theater by Mike Lawler, The Theater Props Handbook and The Prop Builder’s Molding and Casting Handbook by Thurston James, The Prop Master by Amy Mussman, and Making Stage Props by Andy Wilson.

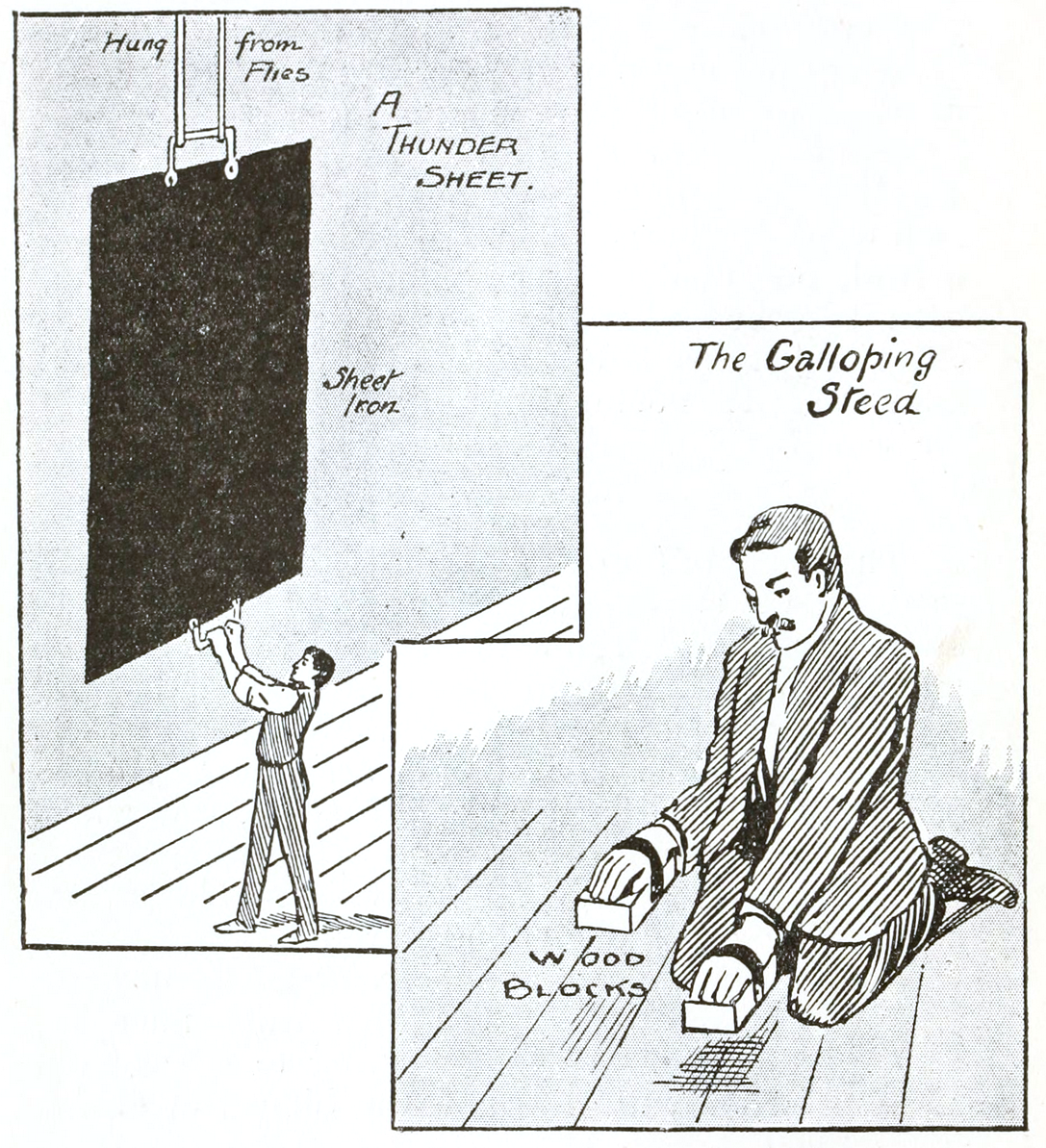

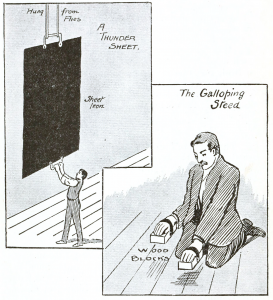

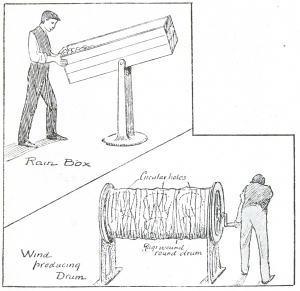

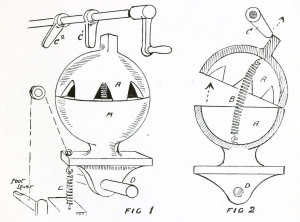

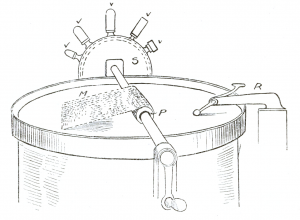

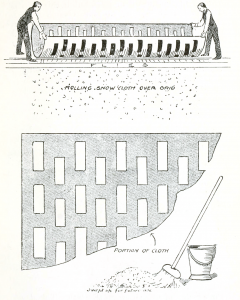

I made some drawings. This year I drew the parts of a sword hilt, illustrated categories of props, and the parts of a book. I also linked to other helpful illustrations and diagrams across the web, such as an upholstery yardage chart, 36 knots, bends and splices, mechanical sound effects, and Nokia cellphones and Legos.

I also like looking at the history of props and prop-making, and wrote the following pieces: Oldest Surviving Masks; Medieval theatre and trade guilds; Props in Henslowe’s Diary; Props in the time of Moliere; The Gore of Grand Guignol; Pre-war special effects; and A brief history of IATSE.

Finally, I reprint articles and parts of books from other authors which talk about the world of props in all its many forms and incarnations. In chronological order, these are the articles: The Property Department in an opera house in 1851; Behind the scenes at the theatre, 1861; To literally steal the show 1868; The secret regions of the stage, 1874; The End of Making Props 1883; Behind the Scenes of an Opera-House, 1888: Introduction, Constructing a God, Technical Rehearsals, A Singing Dragon, Dangerous Effects; The Influence of Properties upon Dramatic Literature, 1889; A Place to Buy Thunder, 1898; Behind the scenes: The Property Room, 1898; Stage Sounds, 1904; Busy Stage Workers the Public Never Sees, 1910; The Unreality of Stage Realism, 1912; Writing for Vaudeville, 1915; Play production in America, 1916; Props in Movies, 1922; Dressing interior sets for the motion picture camera, 1923; Stage-hands union, 1923.

So keep reading, and keep propping. This next year should be just as exciting!