On the second full day of this year’s S*P*A*M conference, we watched a presentation by Rebecca Akins. Ms. Akins has designed costumes for Childsplay Theatre (our host in Arizona) for the past twenty-five years, and has been constructing costumes, puppets, costume props and masks for at least that long as well. She divided her presentation in two parts. The first was on materials and methods she’s used in the past which she now knows to be hazardous to your health. The second was on “new good things”, which are less-toxic replacements for these.

One of her earlier shows was a production of Devils in 1971. She created latex masks, Celastic armor, and sprayed the costumes with aniline dyes. Anyone who has worn latex knows it does not allow the skin to breathe, and the latex masks were very uncomfortable to the actors with the heat and build-up of sweat underneath. Aniline dyes are extremely toxic, and spraying them is a great way to fill your lungs with poison, especially with little ventilation and no respirator.

Ms. Akins used Celastic a lot in those days, starting with Celastic mitres, crowns and wigs for The Balcony in 1969, through at least 1981 with masks for a production of The Pied Piper. For those who are unfamiliar, Celastic is a fabric impregnated with plastic. When you soak it in a solvent, it becomes soft and flexible, hardening to a stiff but lightweight shell when the solvent evaporates. The toxic part is not the Celastic itself, but the solvent used to soften it; common choices include acetone and methyl ethyl ketone (MEK). All solvents are harmful to humans, and can enter the body through the skin, lungs, stomach or eyes. Not all gloves will protect against them, and not all respirators are designed to filter out their vapors.

She mentioned a material I had never heard of called “blue mud cement”. It is a powdery mixture of asbestos fibers and “spackle-y” binders; when mixed with water, the paste will dry hard and lightweight (it was originally developed for plumbing pipe insulation). For a 1974 production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, she created forms in chicken wire, wrapped them in plaster bandages, and coated the whole thing with blue mud cement. It sounds like a mix between Bondo and chopped fiberglass, except that it’s, you know, asbestos.

Cutting and carving Styrofoam with a hot knife or wire is another technique she described; the fumes created when Styrofoam melts are fairly toxic.

In 1984, Ms. Akins worked with fiberglass for the first time to create a mascot head for a Phoenix sports team. Fiberglass creates strong and lightweight shells, but she found the individual particles got into her skin and clothes and irritated her immensely, and the resins used give off a lot of fumes while curing; it is also an inhalation hazard when sanding the hardened fiberglass. She used fiberglass again in 2002 with more adequate protection (ventilation, a respirator and thick sleeves), but decided it was too much of a hassle to continue working with it.

The second half of her presentation dealt with “new good things”, that is, newer materials which attempt similar results with less toxicity. Examples include Fosshape, Thermaflex (or Wonderflex), leather, fabric, paper and silicone casting gels.

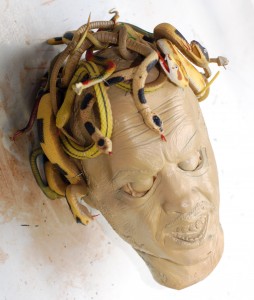

Paper, used in papier-mâché, is one of the oldest prop-making materials. Indeed, Ms. Akins has been using it since at least 1973 for a production of The Bacchae. She continues using it even today. She showed us a number of masks and puppet heads she has constructed over the years, many of them made with a mix of paper pulp, sawdust, and PVA glue. This gives her a material which she can sculpt and form like clay, but which dries to a lightweight and sturdy piece which is paintable and sandable. The fact that some of these pieces have been on tour since the mid-90s is a testament to their durability.

Fabric is another less-toxic material. She uses soft sculpture a lot for puppets; fabric, thread, fiber fill (stuffing) and paint are the only materials needed to make three-dimensional shapes.

She showed us a number of examples of “found objects as materials”. An old leather handbag became a dog mask, a group of woven baskets transformed into a camel, and dryer hoses turned into snakes and an elephant’s trunk. Though using found objects has long been a staple of propmaking, Ms. Akins reminded us it remains a fairly non-toxic–and environmentally friendly–method, even today. Below is a photograph of a dog mask made out of wooden bowls.

In 2004, she began using Fosshape to make a head for a production of Big Friendly Giant. Like Themaflex and Wonderflex, Fosshape is a plastic-impregnated fabric which becomes soft and pliable when heated, and retains its shape when cooled. In many ways, it is similar to Celastic, except you use boiling water or a heat gun to soften it, rather than a bucket full of solvents.

Finally, she described her first forays into using silicone mold materials. She would make a model in clay, mold it in silicone, and then cast it in resin. In one case, she mixed resin and Bondo together to make a puppet head; this gave her a translucent pinkish head which looked a lot like skin.

At the end of her presentation, Ms. Akins reminded us that whatever materials and methods you choose, you should endeavor to make the prop with as much care as possible. She left us with these closing words: “The more gorgeous a thing is, the more respect it is treated with.”