I have a new video up at the Prop Building Guidebook companion website video page. This one shows basic sculpting and carving of foam. I filmed myself while sculpting a small head for the Vicky “doll” in the recent production of Cloud 9 which we just opened.

Tag Archives: foam

Milky the Cow

I recently finished some work on a production of Into the Woods at Elon University. The students hired me to build the animals (some may call them puppets). Milky the Cow is one of the main animals, appearing in many of the scenes. I began by sculpting a cow head in white foam.

I gave the head a coating of papier-mâché. The design of the show used a lot of found object and natural material arranged to suggest a forest, rather than attempting a realistic portrayal of one. So the construction of the head proceeded in a manner to highlight the fact that it was a handmade object, rather than attempting to completely mimic an actual cow’s head.

The body was a separate piece; it was just the torso, tail and udder, without any legs. They were basing their design off of the Regent’s Park production (which transferred to the Public Theater this past summer, though I left just before it came).

I started with a structure made of a cardboard tube “spine” and some bent PVC pipe to define the shape. I than began wrapping vines around to create the outer surface. Everything was wired in place, but I also added some twine to make it appear as though it was lashed together.

Next for the head were some ears. I patterned and sewed them out of muslin, with a piece of styrene inside to give it some stiffness. Once the ears were on the head, I heated them with a hot air gun so I could curl and shape them. When cool, the styrene retained that shape.

The head got a coat of grey primer, followed by a dry brush of off-white over top. I glued a dowel coming out of the back of the head so the handler could hold onto it and manipulate it around.

The udder was a few pieces of red fabric which I patterned, sewed, and stuffed with polyester batting. I lined the inside of the body with some screen material so the actors could throw objects inside as Milky “ate” them, and they would be easy to retrieve after the show. I added some raffia to beef out the body since the vines did not give enough coverage on their own.

So there you have it; one Milky the Cow!

A Disappearing Turkey

To all of my American readers, I hope you have a Happy Thanksgiving this week! Brian Wolfe from Costume Armour sent me some photographs of a trick turkey they recently created, which seems apropos to the holiday.

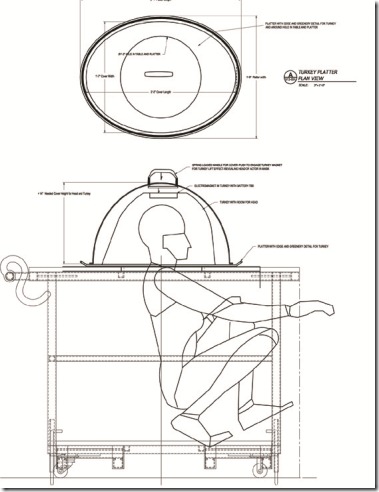

For this trick, a waiter needed to walk in with a food cart. He lifts the lid off of a covered tray revealing a delicious roast turkey. He replaces the lid, and the next time the lid is removed, the turkey is gone. Instead, an actor’s head is on the tray, and the actor begins to speak.

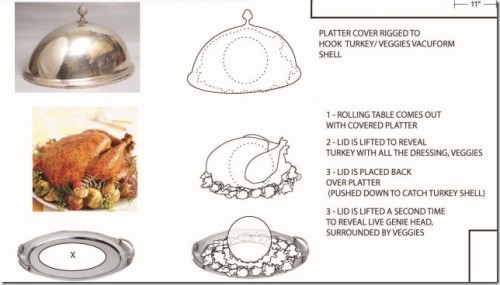

This is the drawing he shared with me:

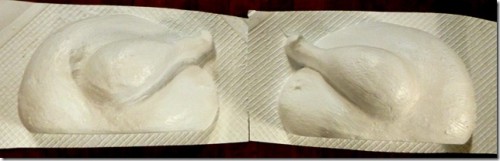

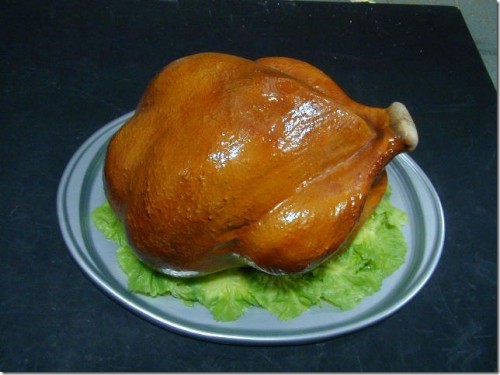

They needed a giant, oversized turkey with enough room inside to fit a head; it also needed to be light enough that it could be lifted along with the tray (you will see why in a minute). They had a rubber turkey in stock, but it was too small and heavy. So they decided to vacuum form a new one. They carved the turkey in foam, made a two-piece mold, and vacuum formed it in 0.04″ Kydex plastic.

They cut out the pieces, glued them together, and painted them. Next, they cut a large hole in the bottom:

The tray was also vacuum formed, this time in a heavy 0.093″ Kydex plastic with a metallic finish. The bottom was formed over a wooden mold, while the lid used a plaster mold. They also added some artificial lettuce which was bought.

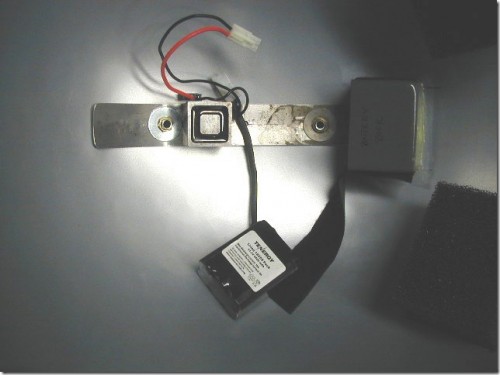

A brass drawer pull completed the look to the lid. The small black rectangle next to it in the photograph below is a small toggle switch:

When the waiter flips this switch, a small battery-powered electromagnet turns on (shown in the next photograph). The turkey had a small piece of flat steel hidden on top which is grabbed by this magnet. So when the magnet is on and the tray lid is lifted, the turkey travels along with it, hidden from the audience’s view.

The diagram below illustrates how the whole trick was set up. I’ve seen this same basic principle carried out in a number of different ways, but the combination of the hollow turkey and electromagnet makes this execution especially elegant; you can control whether the turkey or head is visible simply by the flick of a switch. The actor underneath does not have to do anything.

Hope you enjoyed this! Have a Happy Thanksgiving!

Making Fake Drinks

“As a substitute for tea, wine, whisky or brandy he serves to the actors water colored with a piece of toasted bread to suit the shade of the desired liquid and then strained. This, by the way, is not a device of modern times.

It comes from the days of Shakespeare, according to stage tradition. Sometimes ginger ale or tea is used, but these are not favored generally because they will not suit all tastes.

To one actor the ale is too pungent, to another the cider is too sour, while the third may not be able to take tea without milk, which, of course, could not be used without impairing the color of the drink. So toast-water has been accepted as the regular thing, agreeable to every palate.”

-The Morning Call, San Francisco, December 25, 1890, pg 19.

A toast to drinking! Playwrights love to make their characters drink. More popular than eating on stage, drinking on stage can be found even in plays where it is not directed by the text; a bottle of booze or well-concealed flask is a common comedic bit or a way to add layers to a character. It’s not surprising; nearly every culture through the history of civilization has had some form of fermented drink.

Many of the fake drink recipes I’ve come across over the years deal with alcoholic drinks. Very few plays feature characters drinking fruit juices. Further, drinking real beer, wine or liquor on stage is mostly a bad idea for your actor’s health and for the integrity of the show. You can find anecdotes of great stage thespians who drank real spirits while performing in a play, but these are the rare exception rather than the rule. Other drinks need stage substitutes as well. Sweet or syrupy drinks cause phlegm, which affects an actor’s vocal performance, in what some call “frog throat.” Milk or chocolate–based drinks can do the same. Coffee or tea is sometimes used if it does not need milk added, or if a milk-substitute can be found. De-caffeinated versions are preferred because most shows commence in the evening.

A number of other factors can affect your fake drink recipe. The stage lighting of the scene it plays in can alter the look of it; what looked good in the prop shop may look wrong on stage. It is often helpful to have a bottle of the real stuff on hand for comparison. Other times, the director or designer may want to veer away from complete accuracy and request a whiskey which is darker than real whiskey, or a red wine that is redder than real red wine. The recipe you come up with needs to be economical and consistent. It is no good to come up with a complicated method which either takes too much preparation time or results in every batch looking different. You must also consult with your costume department if the drinks are spilled or splashed, or if they are strongly-colored, as is the case with red wine. Some recipes stain more readily than others. Finally, pay attention to the packaging and accoutrements surrounding your liquid; drinking has a lot of accessories and rituals which, if done properly, can help sell the idea more effectively than endless experimentation with your recipe. I should also mention that if a drink starts in an opaque container and is poured into an opaque cup, you may not even need to use anything other than water.

It should go without saying that gin, vodka or any clear liquor can be imitated with plain water. If you wish to serve a gin and tonic though, a tonic water would be better than plain. A vodka and Red Bull requires just Red Bull (or a non-caffeinated/unsweetened look-alike).

I’ve never run across or used the “burnt toast” method mentioned in the quote above, but another old standby in the prop person’s bag of tricks is using cold brewed tea for various dark liquors and even some wines. I’ve seen it mentioned in texts as early as 1907. The varieties of teas available gives you an endless selection of colors and opacities, and further looks can be achieved by varying the amount of time the tea seeps or by diluting the tea afterwards. Whiskey, scotch, bourbon, sherry and others can all be made. We’ve even found “red zinger” teas which can pass for red wine on stage. Though neutral on the vocal cords, some actors dislike the taste. In some cases, this may be preferable, as it forces the actors to sip their drink in a realistic matter, rather than chugging down enough whiskey to kill a horse in a single scene.

Another old trick for these drinks is using a small amount of burnt sugar solution in water. Caramel coloring is a form of burnt sugar; you can buy it on its own or use diluted caffeine and sugar free colas which have gone flat. Some props masters have even diluted these ingredients enough to make a white wine substitute. You can also find cola concentrates for use in home soda makers, like a Sodastream, though be aware that the plain versions will still contain sugar and caffeine. A small amount is all that is necessary for a convincing whiskey, while a few drops may be all that is needed for a white wine.

Cheap and/or watered-down apple juice has found its way as a substitute for whiskeys and white wines as well. I have also heard of cranberry juice, blackcurrant juice and cherry juices used for red wine, and diluted grape juice or weak lime juice substituted for white wine. Experiment with combinations of ingredients; many a prop master has found success by mixing one of the above fruit juices with a bit of flat cola for the perfect blend of color and translucency.

Food coloring can be an economical solution, particularly when crafting fake beverages in great quantity. A bit of red and a touch of blue can appear to be red wine. One drop of green may be all that is needed for a convincing white wine. Again, success may be found by adding a touch of food coloring to one of the above recipes.

Champagne is a bit tricker, especially when the director wants to see the bubbles, or worse, when they want a bottle to open with a convincing “pop”. The mechanics of pressurizing and corking a champagne bottle are beyond the scope of this article, but in many cases, ginger ale is the closest substitute. I’ve run across some older recipes that call for using either charged water or a bicarbonate of soda with similar coloring as the white wine recipes above, but this may be adding a layer of complexity which is unnecessary.

Beer can be even trickier. Often, the only convincing substitute is a low-or-no alcohol beer if your actors are okay with that. A convincing head can be achieved with cocktail foam, such as Frothee Creamy Head. You can find recipes to make your own using egg whites (or powdered egg whites if you are squeamish about consuming raw eggs) and an acid such as lemon juice, but again, this adds to the complexity of preparation.

Milk can be tricky as well. I mentioned above that milk fat can lead to frog throat, so skim or nonfat milk can be substituted. Some actors are lactose intolerant, so a non-dairy alternative is called for. Some prop masters have used powdered non-dairy creamer in water, others have used baking soda in water, though I imagine that must taste unpleasant. Diluted milk of magnesia has been used in the past, though if too much is consumed, it can have, er, dire side effects. Unsweetened coconut or rice milk may also serve as suitable substitutes. These days, your health food store may have all sorts of convincing, albeit pricey, lactose-free milk-substitute drinks.

The Most August Links

I am in North Carolina for a few more days, but return to New York City next week, so I will have more time (and a real computer) to spend on writing. Until then, here are some useful sites to satisfy your prop-reading needs:

PDN’s Photo of the Day has some wonderful photographs of Pamplona’s San Fermin festival, where giant puppets run around beating children.

Speaking of puppets, Project Puppet has a great tutorial on adding facial features to your puppet characters. It covers everything from cutting the shapes out of soft foam, to patterning and covering them with fleece.

Rich Dionne continues his series on budget estimates in theatre with one of the hardest variables to estimate: the cost of labor to complete a project.

Some brief, but interesting, prop facts about the upcoming Fright Night remake. I also found another article which has some additional fun facts.