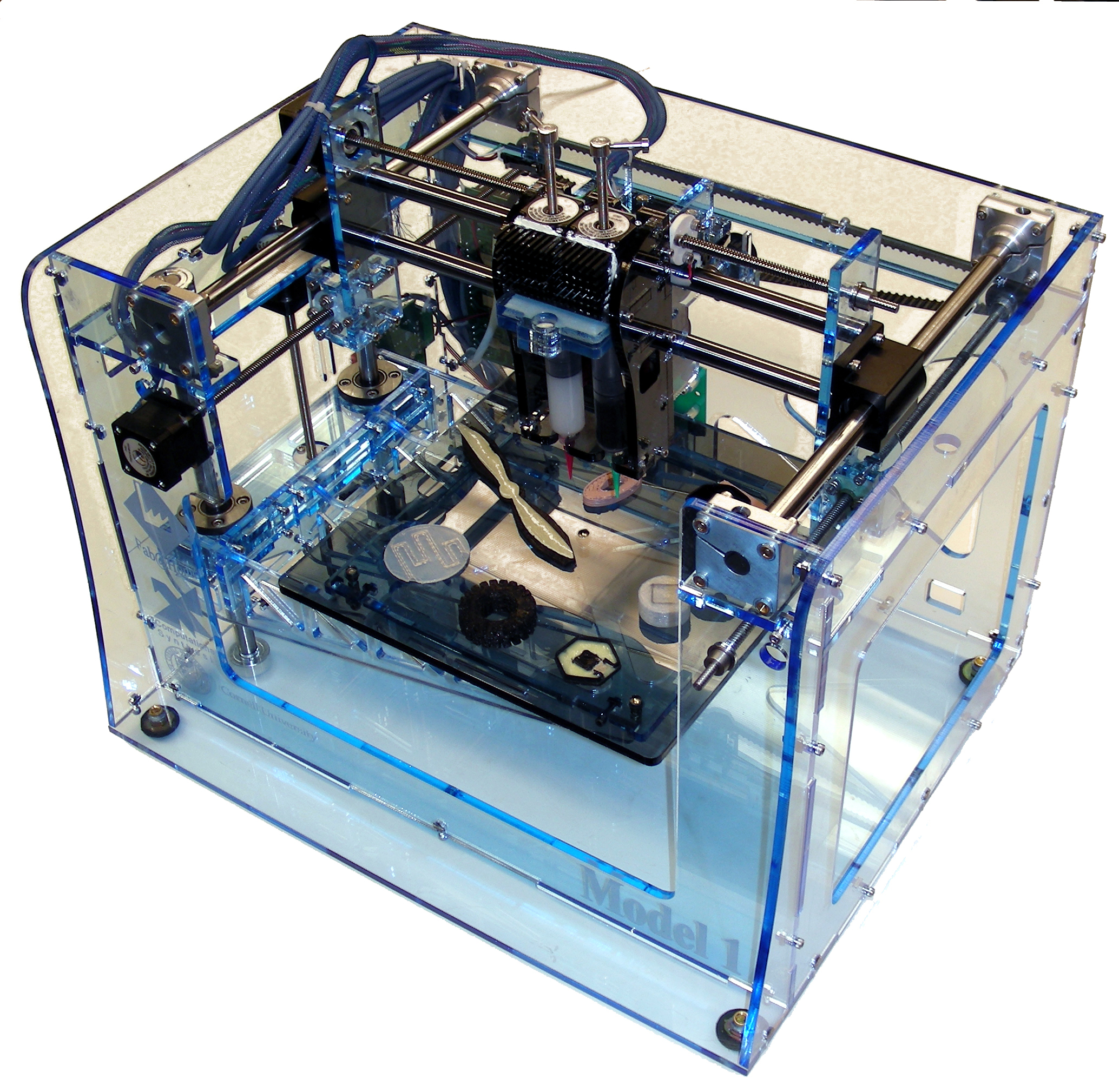

I first wrote about desktop fabrication on this blog over a year ago as part of my “Future of Making Props” series. This weekend, I got to see a number of 3D printers in action. For those who don’t know, 3d printers build an object from a 3D CAD file by laying down very thin layers of plastic one at a time. This weekend at Maker Faire, I got to see a number of the cheaper DIY machines in action: MakerBot, RepRap, and Fab@Home were all there.

I’ve been excited about this technology for prop-making for awhile, as you can basically buy a complete MakerBot Cupcake Kit for around $700 and start printing your own three-dimensional plastic pieces. I’m a bit less excited after seeing what the finished pieces look like. They do not have that great a resolution, and there is a lot of clean up you would have to do to it. Let’s say you needed a small bust of Mozart for your play and you wanted to make it yourself. You would have to develop or make a three-dimensional computer file of the finished piece, which takes time and requires a completely different set of skills than sculpting it in clay. You would need to purchase and maintain a 3D printer. The printing process itself is rather slow; for a larger piece, you most likely would need to leave it running overnight. Once the piece is printed, you still need to sand it and clean it up, and only then can you mold it and cast it. Once you combine the time and money it would take to do all that and compare it to an artisan sculpting and carving a piece, the artisan still wins hands down.

That’s not to say they are without merit. At the moment, their draw is less as a means to an end then as an end itself. You should build and modify your own 3d printer if you are interested in building and modifying your own 3d printer. If you just need the objects it can produce, there are far less-circuitous routes to get there. As prop-makers and prop masters though, it is important to keep an eye on this kind of technology and be prepared to take advantage of it when it matures. It is a game-changer. It has the potential to transform prop-making as much as the introduction of synthetic materials has in the past century, or the invention of power tools to replace hand tools.

You can see they kinds of things which can be made by these machines at Thingiverse, which brings up another advantage of these machines. Once you create an object which works, you can make another just by hitting “print”. You can also share the file with anyone else who has a printer. Thingiverse is a site where you can share your own creations or download other people’s. To put it simply, you do not even know how to use 3d computer software to get things to print. Someone else can do it. That other person does not even need to be in the same location. You can email someone on the other side of the world a picture of what you want and they can email back the computer file you need to print it. I can envision a time when prop masters maintain their own library of printable objects much like they share files for paper props now.

This is already happening with websites like 100K garages or shops like TechShop. TechShop has all the fancy machines like CNC routers, 3d printers, laser cutters, plasma cutters, milling machines, as well as the non-fancy but necessary tools like welders and sanders. At Maker Faire, they were advertising that they were opening up a location in New York City in 2011. It’s very exciting.