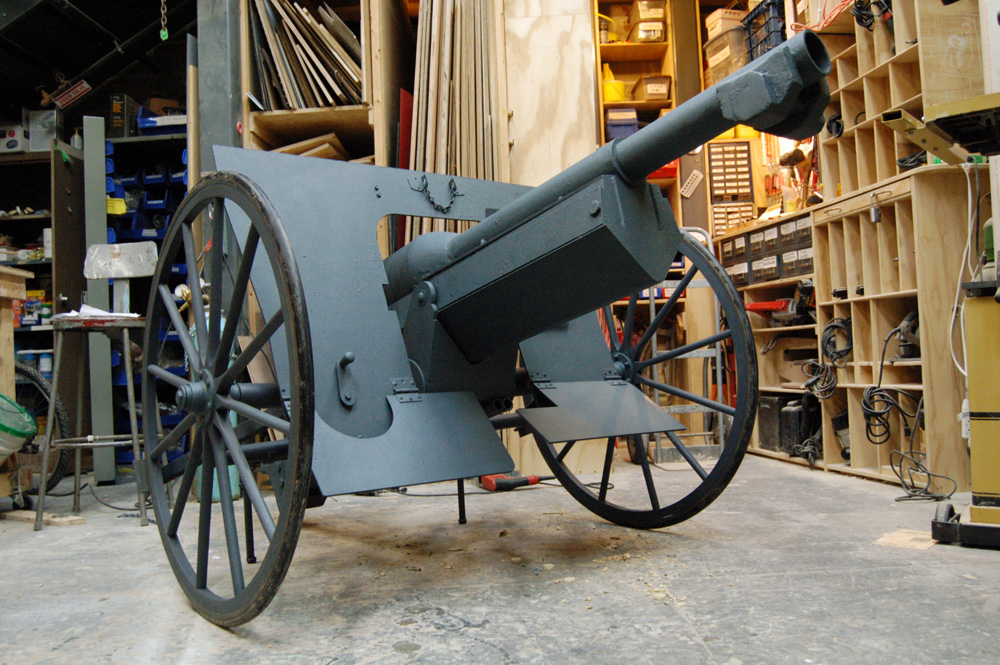

Last week, I showed the beginning stages of a French 75mm field gun I was building for this summer’s Shakespeare in the Park. You can see the construction of most of the structure in that post. Today I’ll continue with the addition of detail, painting and finishing touches.

Tag Archives: construction

A New Prop for Shakespeare in the Park

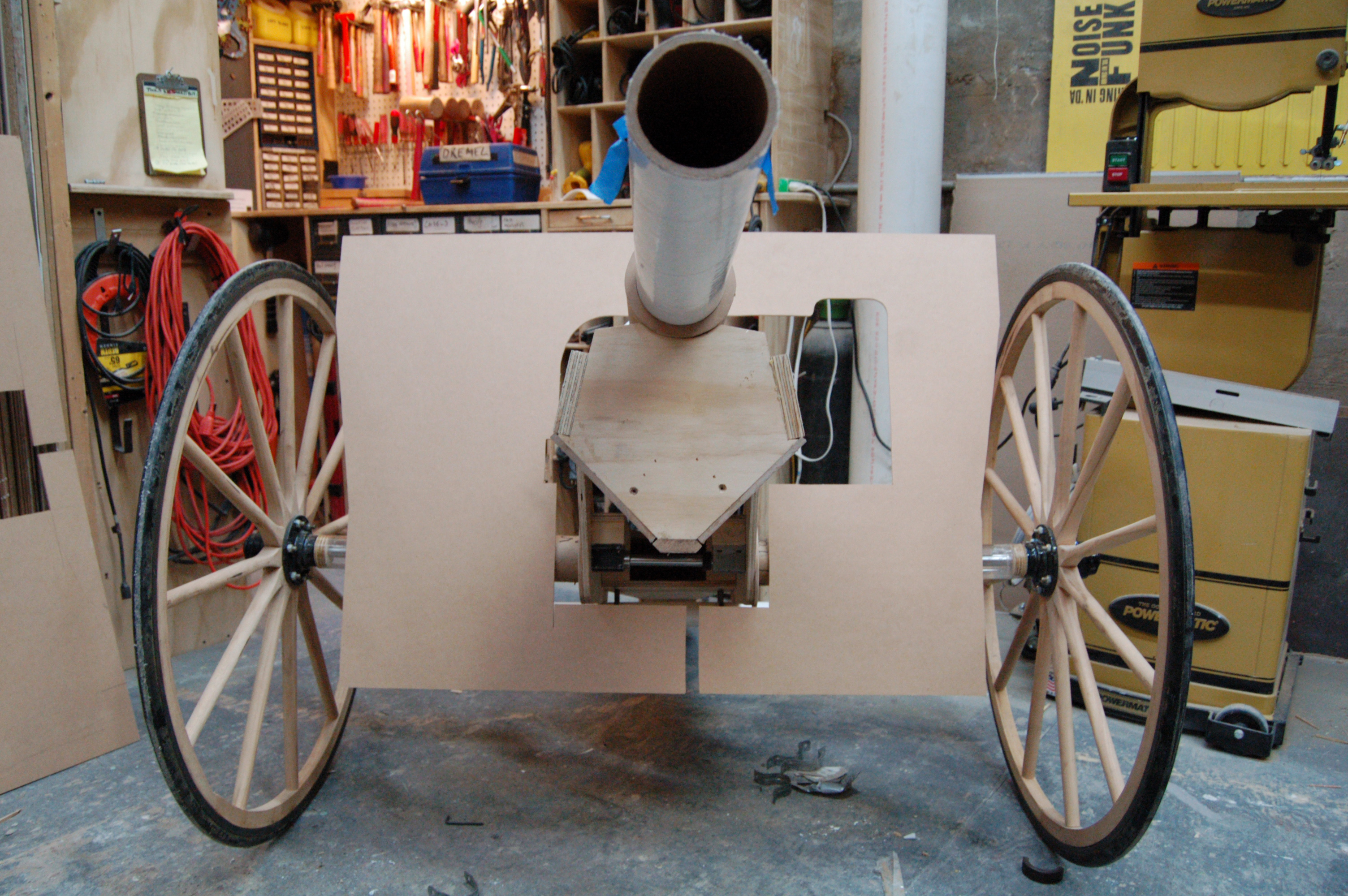

Here’s a quick sneak preview of one of the props I am building for one of the shows in this summer’s Shakespeare in the Park.

Try to guess what it is before looking though all the pictures. Continue reading A New Prop for Shakespeare in the Park

Yoruban Sword

I made this decorative Yoruban sword back in 2004, when I was attending Ohio University and had a lot more beard.

The show was called “The Gods are Not to Blame”, and it is a Yoruban retelling of the Oedipus Rex tale from Ancient Greece (the Yoruba people are one of the largest ethnic groups in Western Africa, with a cultural history of hundreds, if not thousands, of years). My future wife was the set designer on this show, and nearly all the props had to be constructed to be completely authentic; her design involved extensive research into Yoruban artifacts, furniture, and design.

This sword, while appearing like a tradition sword, was built using very modern methods. It’s actually a fairly simple construction, although it has a few hidden tricks. I carved the handle from a piece of poplar, while the blade is taken from a sheet of steel plate. I traced the shape onto the steel and used a plasma cutter to cut it out. I also cut the cross shape out with the plasma.

Now for the hidden fun part. I took a steel rod and sharpened one end to a point. On the end of the tang of the blade, I notched a “V” shape. This is where the sharpened end of the rod went, and I welded the two pieces together; the reason for the sharpening and the notching was to give me a lot of surface area to attach my welds to.

I then had to drill a hole all the way through my carved figurine for the rod to slide into. I needed an extra-long drill bit for this part. I also notched the bottom for the tang to slide into. It was like cutting a mortise for a metal tenon. This step was necessary to keep the handle from spinning around the rod.

I threaded the end of the rod which was sticking out of the top of the figurines head, and tightened a nut down; this is how the handle remained attached to the blade. For one final little touch, I drilled out the top of the head so the nut could fit down inside, and then filled the whole thing over with some Bondo auto-body filler. The nut was now hidden within the top of the handle–with the unfortunate side effect that the handle was now permanently attached. Since this was a decorative sword and not a stage combat weapon (the blade was mild steel, and not to0l-hardened like a weapon’s blade), it would hopefully not need routine maintenance and tightening.

I traced the designs onto the blade from my full-scale drawing and engraved them with a Dremel tool. For my final step, I stained and sealed the handle.

It was a very hefty sword and a lot of fun to swing around. One day, I wasn’t paying attention while swinging it around, and I accidentally cut all my facial hair off. And that, my friends, is the secret origin of “Clean-Shaven Eric”.

It was a very hefty sword and a lot of fun to swing around. One day, I wasn’t paying attention while swinging it around, and I accidentally cut all my facial hair off. And that, my friends, is the secret origin of “Clean-Shaven Eric”.

Design Briefs

In fields such as graphic design, design briefs are used to define the scope of the project. A design brief is a collection of information defining the intended results of a project, as opposed to the aesthetics.

A good prop master or artisan has internalized the process of creating a design brief. The most important consideration in determining the construction of a prop is figuring out what the prop needs to do. For more complicated props, it may be helpful to actually create a design brief.

The first and most important part is asking questions to determine a prop’s needs. Suppose you want to create a table. Your questions may include:

- How tall does it need to be?

- What size is the top?

- How is it used?

- What is the finish on the table? Stain? Paint? Raw material?

- What material is it made out of? More appropriately, what material is it supposed to look like it is made out of?

Most props artisans know that when a table is requested, you should automatically ask the following questions as well:

- Will actors be climbing on top of it?

- Will actors be dancing and jumping on top of it?

- How many actors at a time will be on it?

I swear, some directors only want tables so they have a place for actors to dance.

If you were just building a regular table, the information you need for your design brief may be complete. As this is a theatrical table, you have some additional questions to ask:

- How does it need to come on and off stage?

- Where is it stored backstage?

- Where is it being built?

Why does the last question matter? Most props are built in one location (the prop shop) and transported to another location (the stage). Whenever you are transporting an item, it needs to fit through the smallest opening in that path. Often that is a doorway or an elevator. If the stage is on the second floor of a theatre with only a tiny passenger elevator, you need to build the table so it fits in the elevator and can be reassembled once on stage.

Other props will have different questions to ask. The important thing is to determine exactly what a prop needs to do.

How do I make a…?

“How do I make this?â€

It’s the question faced by the props artisan on a daily basis. Whether you work in theatre, television, or film, you will be asked to build an infinite variety of objects for an infinite variety of uses. Props are found in many other places as well, such as advertising, photography shoots, commercial displays and exhibitions. You may also wish to build props for your own personal uses, such as holiday decoration or hobbies. Whatever your reason, you are reading this because you want to know how to build anything and everything.

Sometimes the answers are self-evident. If the scenic designer wants a wooden chair, you build a chair out of wood. But what if the director wants the chair to be broken during every performance? What if the designer wants a prop from a historical period where the techniques and materials used are no longer available to us? Most commonly, what if the production calls for props which have no counterpart in the real world?

The men and women who build props come from the most diverse backgrounds imaginable, and are skilled in an endless number of techniques and processes. They approach the construction of a prop from a variety of angles, honed over years of experience and trial-and-error. The “why†of props construction is often based on which materials they are most comfortable using, or by asking questions from those who have been in the business longer than they.

Is there a way to more clearly define this approach? Is there a “scientific methodâ€, as it were, to apply to every prop whose construction is not self-evident?

If you have any time over this Thanksgiving, leave a comment with any insights on your own process; what informs your decision on how to construct a prop?