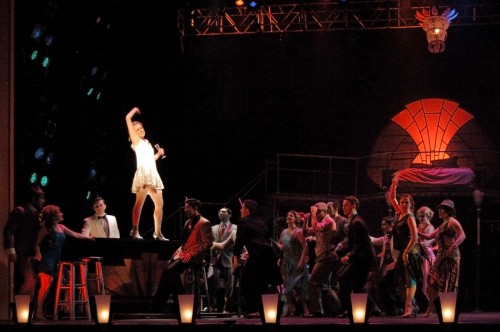

It is a little over a week since Elon University’s Wild Party closed, so I thought I would share some of the props I built while working as the props master on it. First is the sleek Art Deco bar. This production featured a lot of dancing and movement (in fact, the show was more of a dance piece with singing than a traditional musical) and the bar was key in a lot of the dancing. Actors jumped up and down off of it constantly and danced on top of it. Needless to say, it had to be sturdy.

The other hurdle was that I only had a bout a day to build the bar to a point that they could use it in rehearsal; it did not have to be finished, just usable. The bar had a sort of boomerang or banana shape to it. I knew it would take awhile to layout the shape, not to mention all the pieces I would need to cut that followed the shape but were inset or offset by varying amounts. Since the scenic designer, Natalie Taylor Hart, already had the footprint of the bar drafted in CAD, we decided to CNC these pieces and save some time.

The top was two layers of plywood. We were putting lights in the bar that would shine upward, so the top also had squares to hold three pieces of 3/4″ plexiglass; the squares on the top piece were large enough to fit the plexiglass, while the squares on the bottom piece were a touch smaller to create a lip for the plexiglass to sit on.

I also cut the footrest, a piece for a shelf in the middle, and some formers to nail the wiggle wood to. This pile of pieces would have taken awhile to draw and cut by hand, but with CAD, Natalie just had to copy the same shape over and over again, insetting the front curve by whatever measurement I gave. With this pile of pieces, I just had to cut a bunch of formers and uprights to connect them all together.

I decided I wanted some supports to run unbroken from the top to the bottom of the bar for strength, which meant I had to cut some notches and holes in the plywood that they could run through. If I had more time to figure the whole thing out ahead of time, I would have drawn these into the CAD. Since the pieces were already cut, I needed to measure and cut them by hand. See, even with fancy fabrication machines, you still need a solid grasp of traditional tools to build things.

I built the bar up one level at a time, marking carefully to keep the whole thing square and straight. I positioned the supports so they were nearly above the support below them; they were offset just a bit so I would be able to drive a nail in.

The supports along the front of the bar did double duty as formers, providing a nailing surface for the wiggle wood I would add later. I tried to keep the back as open as possible so it could be used as shelving to store all the props; the set was fairly open and skeletal, so the bar served as a place for a lot of the hand props to appear and disappear. The diagonal braces in the photograph above are just to keep the bar sturdy as they use it in rehearsal. Once the wiggle wood was added, I removed them, because the wiggle wood acted as one large piece of diagonal bracing.

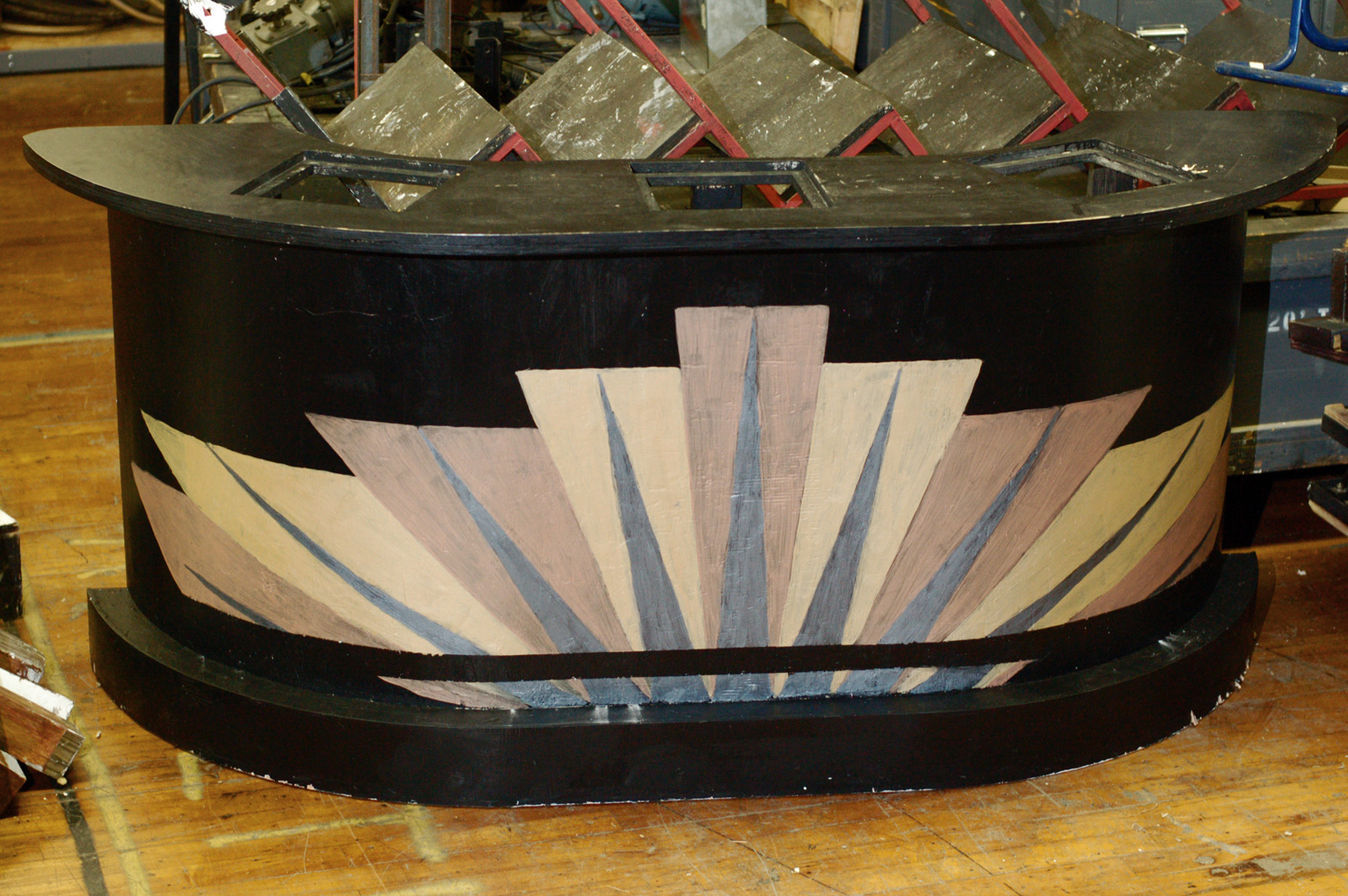

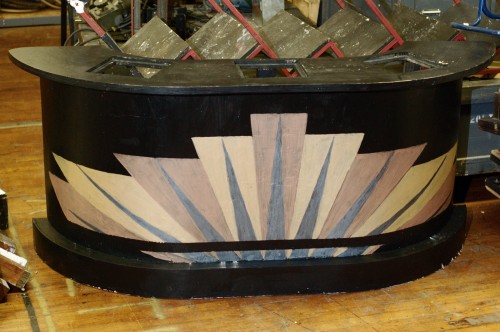

I finished the bar onstage in between rehearsals. The curve was longer than eight feet, so I could not cover it with just one piece of wiggle wood. The center is relatively flat, so I placed a small piece directly in the center; I have found it easier to fill and sand seams between wiggle wood when they are on flat areas. The footrest also got a small strip of wiggle wood after the bar was secured to the wagon underneath it. All the faces got a thin coat of joint compound and a light sanding, and then it was on to painting.

You can see the bar is a bit rough around the edges in the photograph above since I did not have time to take a picture until after strike. The Art Deco design painted on the front was a great touch added by Natalie and her crew. As she also pointed out, despite all the climbing and dancing done on this bar, she never saw it sag or wobble.