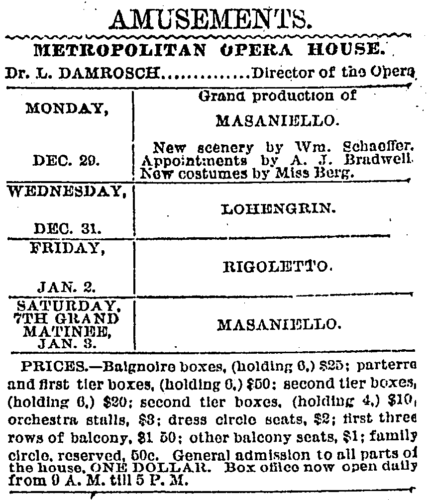

In a previous post, we learned that the first props master of the Metropolitan Opera was a man named A. J. Bradwell, and that he came from a family of props masters stretching back nearly two hundred years. Who were the Bradwells? I’ve been researching them for awhile and wanted to introduce you to the main ones I’ve found: four generations of props masters spanning a time from the 18th century all the way to the 20th century.

William Bradwell (?-1849)

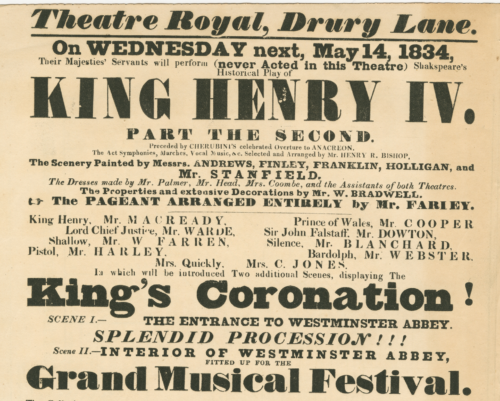

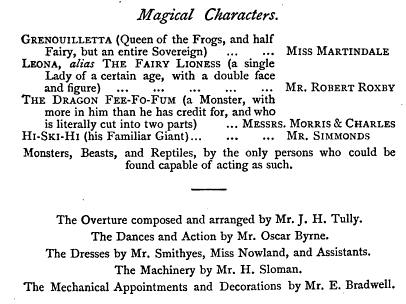

William Bradwell was a theatrical decorator and machinist in London. He worked on many of the props, tricks, and effects at Covent Garden from 1806-1839. His work on the pantomimes were so well-known that his name was used to advertise shows as a sign of quality. He was once referred to as “the fairies’ couch maker.†He worked directly under such English stage greats as Dibdin the Younger, Macready, and E.L. Blanchard (in fact, Bradwell hired a young Blanchard as a props running crew at the beginning of his career).

He and his wife Elizabeth had a son named Edmund in 1799.

Edmund Bradwell (1799-1871)

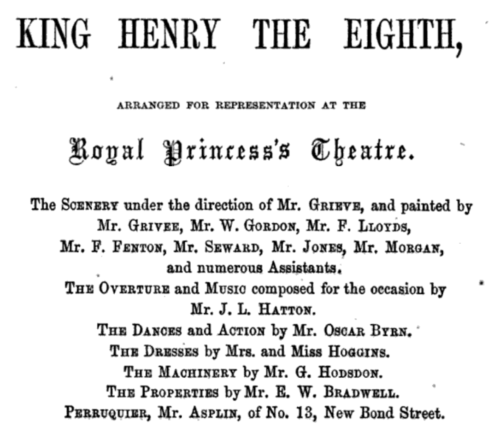

Edmund was working at the Theatre Royal in Dublin until Robert Elliston took him back to London to build properties and machinery for the Surrey Theatre. He worked at a number of theaters, such as the Olympic, Lyceum, and Her Majesty’s Theatre, and quickly developed a reputation for innovative “transformations.â€

Edmund and his wife Margaret had at least seven daughters, and two sons who continued in the business: Edmund William Bradwell, and Alfred John Bradwell.

Edmund William Bradwell (1828-1909)

Edmund William was born in Ireland immediately before his father returned to London. His work as a builder and decorator seems to have been more focused on the decoration of theatre interiors. A number of theatres that opened or were renovated around this time had some of the design and decoration executed by E. W. Bradwell.

EW and his wife Elizabeth had three daughters and one son. The son, William Edmund Valentine Bradwell, appears to have followed in the family business at least a bit.

William Edmund Valentine Bradwell (1858-1938)

William was born on Valentine’s Day. His occupation was listed as both a builder’s artist and a decorative artist in surviving paperwork. I don’t know much more about him than that.

Alfred John Bradwell (1845-after 1891)

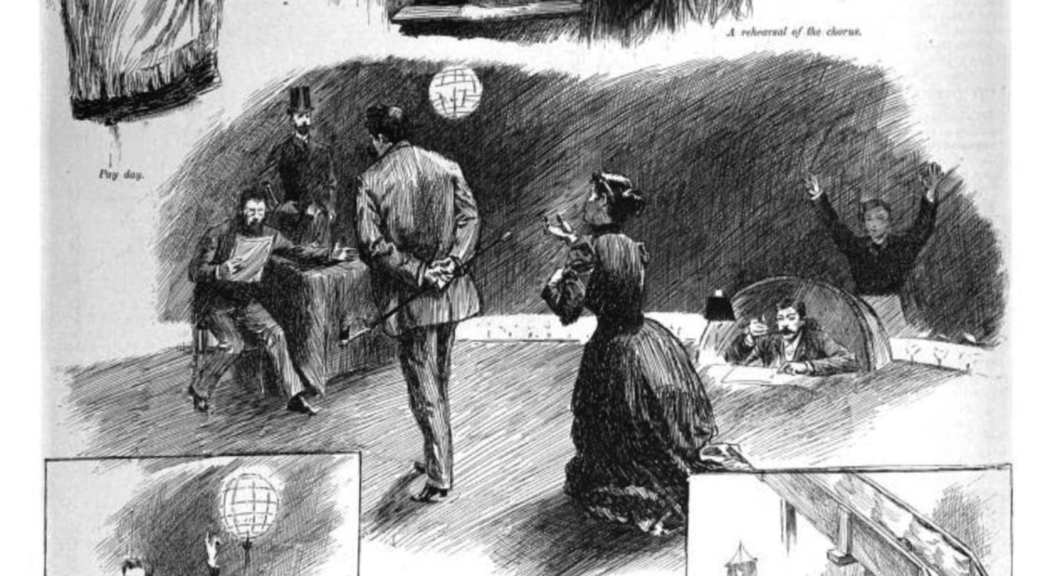

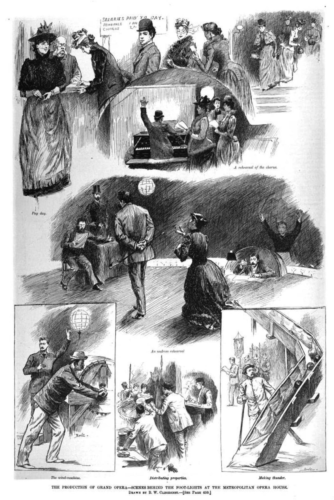

Alfred was Edmund’s son and Edmund William’s brother. His career began as an assistant to his father on a number of pantomimes throughout London, learning to accomplish all sorts of mechanical transformations and properties. He built his own reputation as a pantomime properties artisan at Drury Lane after his father died. He emigrated to the United States and became the first properties master at the Metropolitan Opera when it opened in 1883. He also trained Edward Siedle, a properties master who would go on to become technical director at the Met, transforming it into a technical powerhouse in the early twentieth century.

He and his wife Annie had a number of children, with their son Herbert Augustus Bradwell continuing the business. He had another son, Ernest Athol Bradwell, who appears to have worked as both an actor and a stage carpenter over the years.

Herbert Augustus Bradwell (1873-1911)

Herbert was born in London, but mostly grew up in New York City after his father joined the Met Opera. He became quite the well-known creator of electrical and mechanical effects on stage. In the early twentieth century, Coney Island was the home of massive live spectacles, such as volcanic eruptions and train crashes. Herbert was coproducer and an effects creator for one of the most successful ones known as “The Jonestown Flood,†in which an entire town was flooded during every performance. When this closed, he produced his own show in the same building known as “The Deluge,†a recreation of the Noah’s Ark story. It was wildly successful, and he transferred the show to London. It failed there, and a second attempt at a disaster spectacle in Brussels ended up burning to the ground. Now broke, he brought his family back to New York, and ended up starving himself to keep his family fed. This led to a mental breakdown that put him in the hospital, where his heart eventually gave out. He died at the young age of 44, completely destitute.