The following is excerpted from “Writing for Vaudeville” by Brett Page, published in 1915:

Into the mimic room that the grips are setting comes the Property-man–”Props,†in stage argot–with his assistants, who place in the designated positions the furniture, bric-a-brac, pianos, and other properties, that the story enacted in this room demands.

After the act has been presented and the curtain has been rung down, the order to “strike†is given and the clearers run in and take away all the furniture and properties, while the property-man substitutes the new furniture and properties that are needed. This is done at the same time the grips and fly men are changing the scenery. No regiment is better trained in its duties. The property-man of the average vaudeville theatre is a hard-worked chap. Beside being an expert in properties, he must be something of an actor, for if there is an “extra man†needed in a playlet with a line or two to speak, it is on him that the duty falls. He must be ready on the instant with all sorts of effects, such as glass-crashes and wood-crashes, when a noise like a man being thrown downstairs or through a window is required, or if a doorbell or a telephone-bell must ring at a certain instant on a certain cue, or the noise of thunder, the wash of the sea on the shore, or any one of a hundred other effects be desired.

…

In the ancient days before even candles were invented–the rush-light days of Shakespere and his predecessors–plays were presented in open court-yards or, as in France, in tennis-courts in the broad daylight. A proscenium arch was all the scenery usually thought necessary in these outdoor performances, and when the plays were given indoors even the most realistic scenery would have been of little value in the rush-lit semi-darkness. Then, indeed, the play was the thing. A character walked into the STORY and out of it again; and “place†was left to the imagination of the audience, aided by the changing of a sign that stated where the story had chosen to move itself.

As the centuries rolled along, improvements in lighting methods made indoor theatrical presentations more common and brought scenery into effective use. The invention of the kerosene lamp and later the invention of gas brought enough light upon the stage to permit the actor to step back from the footlights into a wider working-space set with the rooms and streets of real life. Then with the electric light came the scenic revolution that emancipated the stage forever from enforced gloomy darkness, permitted the actor’s expressive face to be seen farther back from the footlights, and made of the proscenium arch the frame of a picture.

“It is for this picture-frame stage that every dramatist is composing his plays,†Brander Matthews says; “and his methods are of necessity those of the picture-frame stage; just as the methods of the Elizabethan dramatic poet were of necessity those of the platform stage.†And on the same page: The influence of the realistic movement of the middle of the nineteenth century imposed on the stage-manager the duty of making every scene characteristic of the period and of the people, and of relating the characters closely to their environment.†(The Study of the Drama, Brander Matthews.)

On the vaudeville stage to-day, when all the sciences and the arts have come to the aid of the drama, there is no period nor place, nor even a feeling of atmosphere, that cannot be reproduced with amazing truth and beauty of effect. Everything in the way of scenery is artistically possible, from the squalid room of the tenement-dweller to the blossoming garden before the palace of a king–but artistic possibility and financial advisability are two very different things.

…

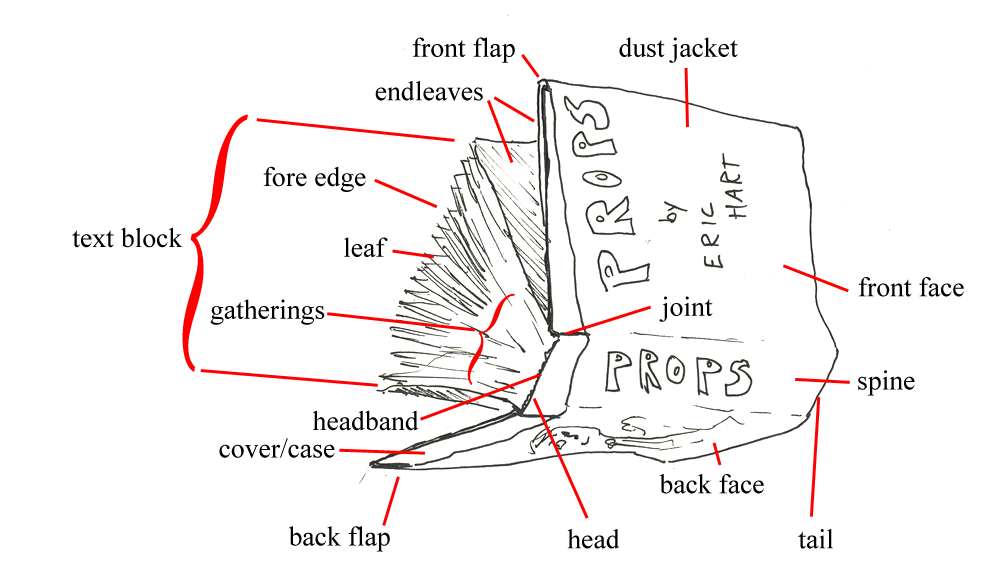

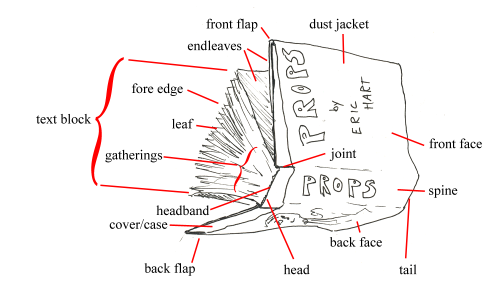

In the argot of the stage the word “property†or “prop†means any article–aside from scenery–necessary for the proper mounting or presentation of a play. A property may be a set of furniture, a rug, a pair of portieres, a picture for the wall, a telephone, a kitchen range or a stew-pan–indeed, anything a tall that is not scenery, although serving to complete the effect and illusion of a scene.

Furniture is usually of only two kinds in a vaudeville playhouse. There is a set of parlor furniture to go with the parlor set and a set of kitchen furniture to furnish the kitchen set. But, while these are all that are at the immediate command of the property-man, he is usually permitted to exchange tickets for the theatre with any dealer willing to lend needed sets of furniture, such as a desk or other office equipment specially required for the use of an act.

In this way the sets of furniture in the property room may be expanded with temporary additions into combinations of infinite variety. But, it is wise not to ask for anything out of the ordinary, for many theatre owners frown upon bills for hauling, even though the rent of the furniture may be only a pair of seats.

For the same reason, it is unwise to specify in the property-list– which is a printed list of the properties each act requires–anything in the way of rugs that is unusual. Though some theatres have more than two kinds of rugs, the white bear rug and the carpet rug are the most common. It is also unwise to ask for pictures to hang on the walls. If a picture is required, one is usually supplied set upon an easel.

Of course, every theatre is equipped with prop telephones and sets of dishes and silver for dinner scenes. But there are few vaudeville houses in the country that have on hand a bed for the stage, although the sofa is commonly found.

A buffet, or sideboard, fully equipped with pitchers and wine glasses, is customary in every vaudeville property room. And champagne is supplied in advertising bottles which “pop†and sparkle none the less realistically because the content is merely ginger ale.

While the foregoing is not an exhaustive list of what the property room of a vaudeville theatre may contain, it gives the essential properties that are commonly found. Thus every ordinary requirement of the usual vaudeville act can be supplied.

The special properties that an act may require must be carried by the act. For instance, if a playlet is laid in an artist’s studio there are all sorts of odds and ends that would lend a realistic effect to the scene. A painter’s easel, bowls of paint brushes, a palette, half-finished pictures to hang on the walls, oriental draperies, a model’s throne, and half a dozen rugs to spread upon the floor, would lend an atmosphere of charming bohemian realism.

Special Sound-Effects fall under the same common-sense rule. For, while all vaudeville theatres have glass crashes, wood crashes, slap-sticks, thunder sheets, cocoanut shells for horses’ hoof-beats, and revolvers to be fired off-stage, they could not be expected to supply such little-called-for effects as realistic battle sounds, volcanic eruptions, and like effects.

If an act depends on illusions for its appeal, it will, of course, be well supplied with the machinery to produce the required sounds. And those that do not depend on exactness of illusion can usually secure the effects required by calling on the drummer with his very effective box-of-tricks to help out the property-man.

…

ARGOT.–Slang; particularly, stage terms.

GLASS-CRASH.–A basket filled with broken glass, used to imitate the noise of breaking a window and the like.

GRIP.–The man who sets scenery or grips it.

OLIO.–A drop curtain full across the stage, working flat against the tormentors (which see). It is used as a background for acts in One, and often to close-in on acts playing in Two, Three and Four.

PROPERTIES.–Furniture, dishes, telephones, the what-not employed to lend reality–scenery excepted. Stage accessories.

PROPERTY-MAN.–The man who takes care of the properties.

PROPS.–Property-man; also short for properties.

WOOD-CRASH.–An appliance so constructed that when the handle is turned a noise like a man falling downstairs, or the crash of a fight, is produced.

View the full text of the book.

by Amy Mussman. No other book more clearly defines how to be a prop master in a contemporary setting. With a publish date of 2008, it is also amongst the most up-to-date props books out there. I feel strongly that if you read and reread this book as well as studying the Properties Directors Handbook by Sandra Strawn, you are armed with as much information as possible to prop a show short of actual experience. This is the book you want if you are in school and someone tells you, “You are the props master on the next show,” and you have no idea what that entails. It is amazing that until two years ago, a book like this had not been written.