The following comes from a 1914 issue of Popular Electricity and Modern Mechanics:

How Expensive Properties are Made

As an illustration of the rapid strides made during the last few years in the production of motion pictures, a sight-seeing trip through the Universal Company’s studios in California uncovers the fact that twenty-five classes of skilled artisans are at present employed in making the properties for a feature film production. It is stated on good authority that half of the expense in producing pictures of the pageant type is incurred before the actual staging of the drama begins. Upon the screen the spectator sees armies in conflict, reproductions of ancient cities wrecked solely for a camera spectacle, streets of forgotten cities swarming with people costumed in conformity with historical record and all properly fitted out with the accouterments of war and habiliments of peace.

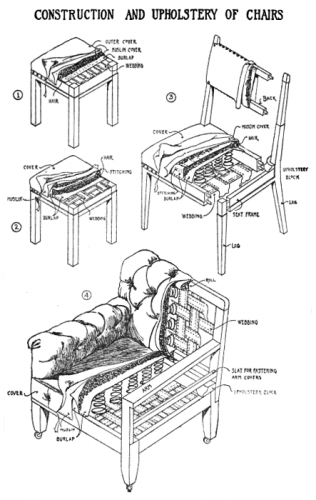

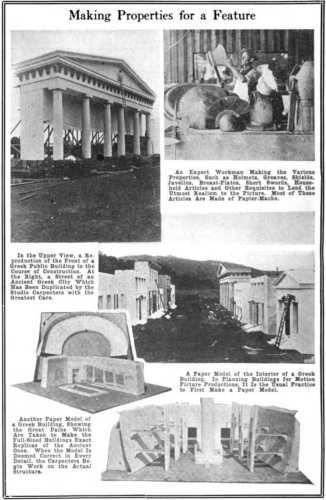

But behind all these shows of pageantry is a large corps of technical experts, craftsmen, mechanics and workmen who transfer these pictures of ancient life from historical records and cuts to so many replicas of the things themselves. General knowledge is all but useless in such productions. When the multiple reel production of “Damon and Pythias” was planned, every detail of scenery and of properties was not only planned and designed upon paper, but everything was modelled in miniature. A replica of the stadium was made of pasteboard. The interiors and exteriors of houses were modeled. Every property was brought down to a definite basis when it was put to the two tests of historical accuracy and adaptability to the camera. During this stage of the work the drafting and the designing rooms had the appearance of a toy shop and would have brought delight to the heart of any child.

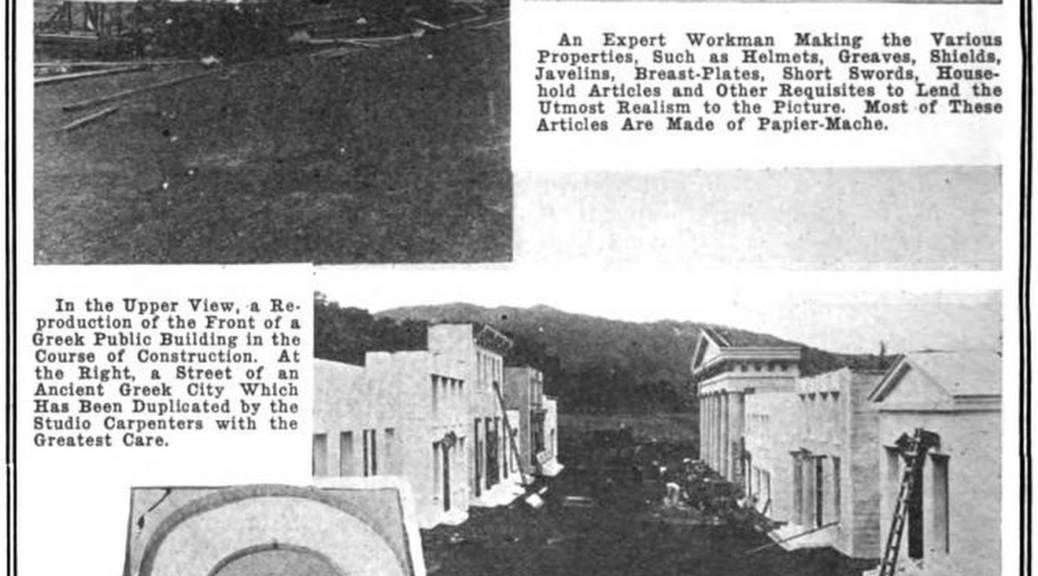

Specifications completed, blue-print designs and colored models were distributed to the various workshops. Helmets, greaves, shields, javelins, breast-plates, short-swords and the smaller household articles were manufactured in the papier-mache department. This work requires considerable time and only expert labor can handle it. The papier-mache department was busy for three months in manufacturing some of the properties for “Damon and Pythias” alone.

Twelve extra seamstresses were employed in the costume department for two months and aside from costumes for the principles, complete outfits were made for five hundred soldiers.

On the company’s ranch, situated in the San Fernando valley, Greek streets, detached dwellings and a stadium grew up and assumed shape and color within a month after the first ground was turned.

The joining and carpenter shops were busy with the wooden properties and frame-work for the large pieces of scenery. Twenty-five chariots were turned out within a period of two weeks. The carpenters work completed, the properties are turned over to the scene painters and decorators, and where iron work was required, to blacksmiths and ironworkers.

In many scenes of this production it was necessary that large pieces of statuary be in evidence. This statuary was made in the company’s shops and only skilled alabaster workers could even attempt the work.

Shops for the manufacture of all description of properties used in motion pictures are something new in the industry. Not longer than two years ago, when a big production was to be made, as few properties as possible were manufactured on account of the extra expense of this work. In those days all properties that could be obtained were rented and the others were improvised.

Thus the advance in this branch of the industry can be appreciated when the fact is brought forth that every property with one exception for the “Damon and Pythias” production was manufactured in the company’s shops. The ancient sets of harness to be used with the chariots was manufactured outside the company’s shops.

“How Expensive Properties Are Made.” Popular Electricity and Modern Mechanics. Ed. Austin C. Lescarboura. Vol. 29. New York: Modern, 1914. 153-55. Google Books. 11 Dec. 2008. Web. 24 May 2017. <https://books.google.com/books?id=1_HNAAAAMAAJ>.