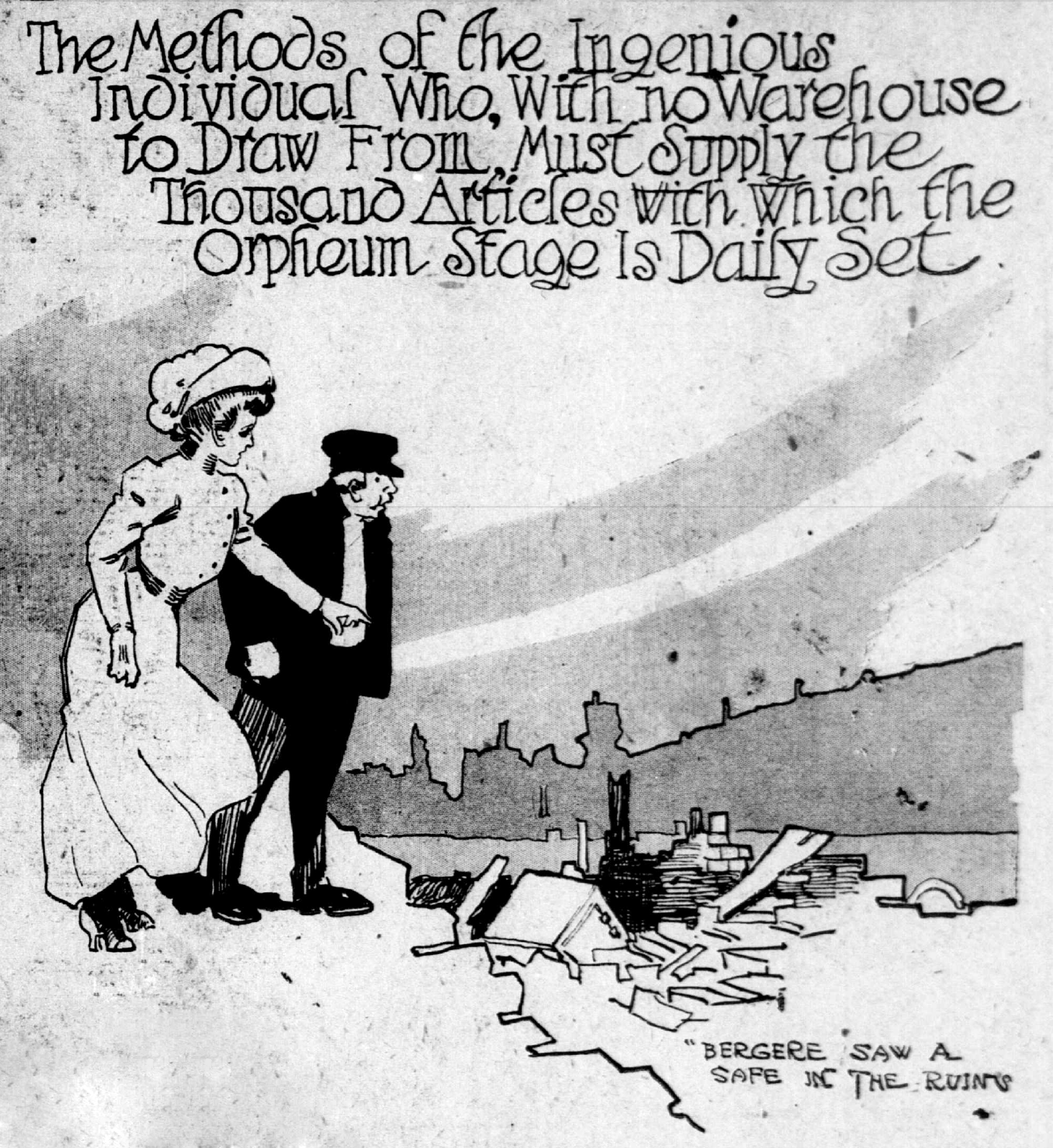

The following is a few select portions from an article in Theatre magazine in 1908. I posted the beginning of the article a few months ago:

by Mary Gay Humphreys

[Mr. Unitt at the Lyceum Theatre said,] “There is a story told of a firm of which one of the members thought a chandelier would look well in the scene. So he went out and bought a fine crystal affair. At the dress rehearsal he noticed it was not lighted, and demanded the reason. He was told that the act took place in the afternoon, and the light was coming in the windows.

“He went to the back of the house where his partner asked the same question, and was told the same answer.

“‘Well, light it. Who in h–l’s goin’ to stop us?’

“The anecdote gives the note which dominates a large part of theatrical production to-day, ‘Who in h–l’s goin’ to stop us?’…

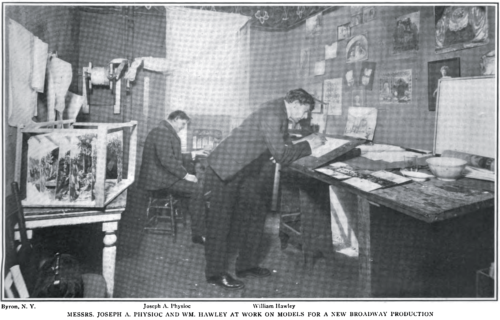

“In the evolution of the scenery of a play, the scene painter is or should have the manuscript to read. In the rush of affairs now he may see only one act, or perhaps only the scenario. In the meantime the stage manager has made a plot and works out the exits and entrances on exact lines. Then the stage manager, author and scene painter get together and consult. That, at least, is the way they must do to get the best results. The scene painter sees only the pictorial side and must be held to the practical necessities of the case. One of these is that the wall scenes must be folded that they can be put in the six feet of doors, for scenery must travel. Fireproofing is another great handicap. This is usually done by painting on fireproof cloth, of which the chemicals are pretty apt to affect the colors. Another difficulty is the harmonizing of real things with the artificial. The use of real antiques, real palms, real flowers and foliage does not produce as successful results as when purely artificial scenery and stage properties are depended on.”…

[Mr. Homer Emens said,] “He must have an instinctive knowledge of effects. A handsome thing may not look handsome behind the footlights. An expensive stuff may look cheap. It is a fact that painted properties look more real than do the real things…

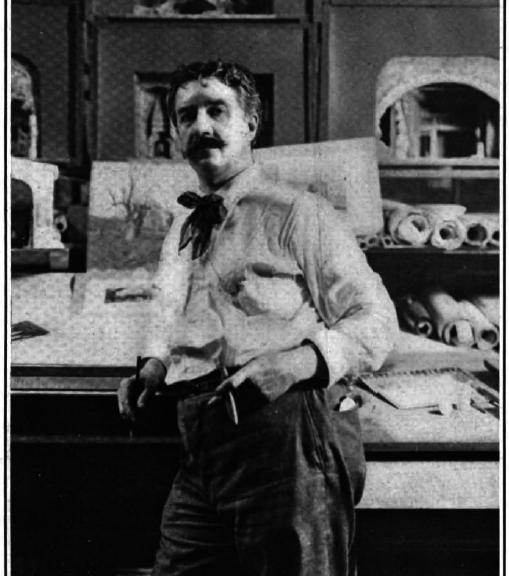

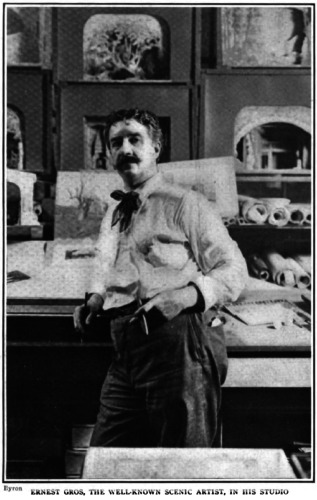

On the edge of things, in one of those architectural monoliths described, Mr. Ernets Gros, the scene painter, was found. His office was interesting with a collection of stage models which could be identified as scenes on the Belasco stage. Here was a scene painter’s library filled with handsome volumes labelled “Greece,” “Rome”—every nation, ancient and modern—books of epochs, periods, archaeology, costumes were represented, as well as periodicals of the most luxurious types in paper, illustration and text. Truly an equipment…

“Modern developments have not helped us in the least,” said Mr. Gros. “Scene painting has in no way advanced. The whole matter lies with the manager. If he is a man with artistic perceptions we have one result. If he depends on his advertising, we have another…

“The first thing the scene painter does is to prepare his model. Then he gives the stage carpenter the measurements. When the frame is ready the painting proceeds. Dry colors only are used; no drop of oil goes into scene painting. Fire-proofing has added to our labors by its effect on the colors. When the scenery is ready comes the problem of lighting, which must be determined by experiment. The electric light is brutal. We try to control it by the use of different media, but in no way can we get at the softness and mystery of gas.”

Stage scenery and the men who paint it. M. G. Humphreys, il. Theatre 8: 203-4, v-vi, Aug 1908.