The following comes from the May 3, 1903 issue of The St. Paul Globe:

When the curtain drops at the close of every act of a drama or opera it is the signal for the players to rush for their dressing rooms, some of the men in the audience to troop up the aisles in search of—a change of air, and the women to chat and—possibly to note what the other women are wearing.

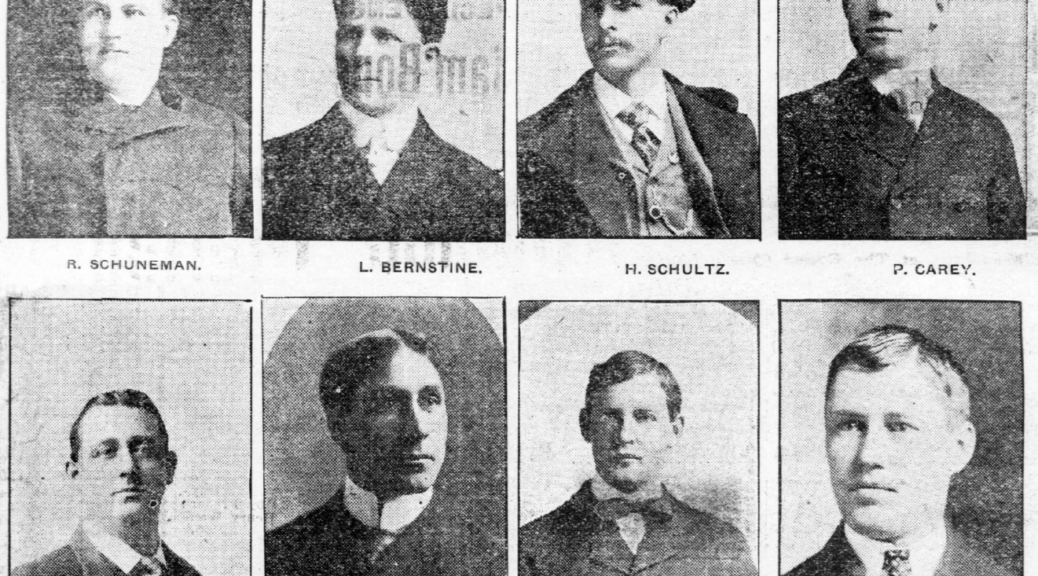

But there is another class of individuals for whom the falling of the curtain means business, and the liveliest kind of business at that. They are the “stage hands.”

As the curtain strikes the floor a stentorian voice cries:

“Strike!”

“Strike!” echoes another equally robust voice, and instantly there is a commotion on that stage that would bewilder a bystander, if he were permitted there at such a time—which he is not.

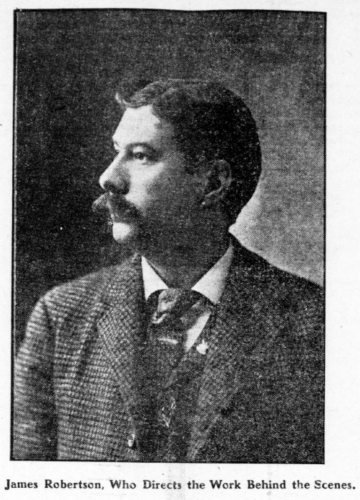

The first voice is that of the stage manager of the company playing at the theater. The second is that of the stage carpenter attached to the house. The commotion is the scurrying about of the stage hands, the property men and the electricians whose duty it is to clear the stage with the greatest possible celerity of all scenery, furniture and lighting paraphernalia that encumbers it. For perhaps the first act presented a street in a large city or the parlor of a rich man’s mansion, and the second is to picture a country lane or the wretched hovel of the poor but virtuous. Hence this bustle.