The following comes from the New-York tribune, July 03, 1910. Written by Charles Bloomingdale, Jr., it tells the story of Charles Hoffner, props master at the Walnut Street Theater in Philadelphia, PA. Incidentally, the Walnut is the first professional theater I’ve ever worked at, as an apprentice stagehand ninety-one years after this article was written. I’ve cut some of the parts that don’t deal with props to keep this short, but you can read the full article at the above link.

Hats off, gentlemen! Age, in the person of the Past, quavers “Good morrow” to you: the old, musty, dusty proproom of the Walnut Street Theater in Philadelphia bids you come in from the garish glare of to-day and sink in its shadows of bygone yesterdays, bids you see and touch the things that Forrest, Booth, Macready, Kean, Charlotte Cushman, Dion Boucicault, and other giants of the stage saw and touched–yes, and used–in those dear, dead days when the drama was palmy. Hats off, gentlemen and enter!

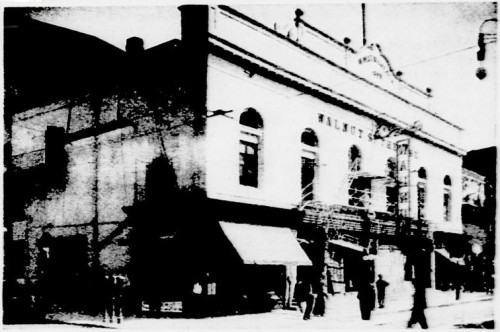

The Walnut Street Theater in Philadelphia is the oldest standing playhouse in America. In February, 1808, it was erected, and for one hundred and two years it has flourished. Once it stood at the outskirts of the town, then the center; now the town has grown many, many miles beyond it. But its proproom–its old proproom; for it has two now–is the same as when Pepin and Preschard opened the theater with a circus and pantomime one hundred and two years ago.

What is a proproom? A proproom is a room for properties. And what are properties? Anything and everything, costumes excepted, used on the stage during a play. A property room looks like the average junkshop, possibly more so. A chair is a property; so is a clock, a cane, a candle, a chain, a corkscrew. And a bottle is a property too, and the forged will and the mortgage papers, a horseshoe, a feather duster, and a paper of pins. And the property man of the theater has all these hundreds of seemingly inconsequential things under his thumb and gets them when they’re needed.

Half a Century in the Proproom

Old Charlie Hoffner is property man of the Walnut Street Theater in Philadelphia. For over fifty years he has had charge of the properties there,–the oldest property man in the United States in the oldest theater in the country. No wonder he loves the old papier mâché helmets and the wooden simitars touched with silver paint that clutter up the old proproom, which long since have outlived their make believe! Grizzled and gray he is; but it’s worth while having silvered hair when one has golden memories. Forrest and Booth and Charlotte Cushman have talked with him; so Fate cannot touch him.

The other day he looked at his treasures in the old proproom. Frank Howe, jr., manager of the theater, was there too, to help Hoffner’s rich memory with a vagrant date or two. Howe is a scholar, a whilom actor, a writer of short stories and plays, a musician, a man whom Art has touched in many places. Fitting, indeed, that he should now, in this latter day, have charge of the playhouse, which in its over a century of life has numbered among its managers such people as Mrs. D. P. Bowers, Edwin Booth, Charlotte Cushman, and John Sleeper Clarke.

Hoffner brushed a half-inch of dust from some hicory staffs. “Them’s old props,” he said, “that were used for most anything, mostly for the witches in Macbeth. The big one here–that one with a fork in it, like the top of the old slingshot I used to have as a boy–that big one was used by Charlotte Cushman in Meg Merrilies. She wanted a stick with a fork at the top so she could rest her elbow there when she spoke those two big speeches of hers. Ah!” and a long memory laden sigh came welling from him, “she was a great and good woman, was Charlotte Cushman!”

A wand with a silver star on it, a little wand only two feet long, caught his eye. “One of the prettiest little girls I ever saw in my life carried that wand the first year I came here, 1858. I know that her first name was Lola, and that she died from catching cold here. Mrs. Bowers was managing the theater then, and Edwin Forrest acted ‘Caius Marius,’ written by R. Penn Smith. Then came the children’s ballet in which the kid that carried this wand appeared; then a pantomime called ‘Jealousy in the Kitchen.’ We opened the doors at six-thirty in those days, and rang up at seven; had to when you had a tragedy, ballet, and pantomime all in one night. Wisht I could remember that kid’s last name!” he said, as he laid the little star capped silver wand on a chair.

A Historic Chair

That chair’s got a history,” he said ruminatively. “You see it’s Gothic, and has four blocks of wood under it, one on each leg. When Forrest played Hamlet with the stock company here, he sat on that chair at rehearsal. Then he gave me ballyhoo; said the chair was so short and dumpy that his chin almost hit his knees. So I had the stage carpenter put blocks under it to raise it from the floor.

“When Booth came along I had the chair down for rehearsal, and he made me take it away.

“‘Too high?’ says I.

“‘No,’ says he: ‘it isn’t right. Hamlet never sat in a Gothic chair like that. He sat in a scoop chair, one with no back and shaped like the letter U. Get a scoop chair.’

“I didn’t have one: but I had it made by nightfall, and Booth sat in a scoop chair in the soliloquy scene. I think the chair’s back in that corner.” and he peered behind cobwebs and dust and scratched his head reflectively: “but I’m not sure.” he added dubiously.

The Pantomimic Ravels

A big head, three feet across from ear to ear, leered down from the rafters. The cotton batting with which it had been stuffed came through in little tufts here and there, like huge snowflakes on a Santa Claus face. But the face was not that of kindly Father Christmas. It was that of a malignant giant, reminding one of those horrible wooden grotesqueries that guard the entrance to a Chinese temple.

Hoffner nodded to the head. “That’s been here a long, long time. It belonged to the Ravel family. Loads of their stuff litter up the place; they left it here. The Ravels were great pantomime folks.–French: three, I think, in the family. They had a spectacle called ‘The Green Monster,’ and they made one change of scene from a dingy graveyard to a beautiful ballroom that was one of the best things I ever saw. Why, it must have been in the ’50s, when back of the stage didn’t boast any of the modern helps for quick shifting: yet the way the Ravels handled those two scenes couldn’t be beaten in swiftness by any of the big companies to-day, with all their modern methods of making quick changes. Yes, I remember that head well,” he added, grinning up at the odd mask which grinned down to him.

Impatient Then as Now

…

“How well I remember Forrest!” he said. “What a man he was, his heart as big as his voice, yet stern and a very fiend for discipline! In those early days there was a rehearsal every day at ten o’clock, and if anyone came in at one minute after ten Forrest would carry on as if everyone of the ten commandments was broken. And, apart from his ideas on punctuality, he was particular about rehearsals; no mumbling of the lines, no perfunctory gestures. Everything must be done at rehearsal just as it was to be done at the performance that night.

“My! don’t I remember the dressing down he gave me one morning!

“He was rehearsing old Dr. Bird’s play of ‘The Gladiator,’ and I had a new set of chains made with handcuffs which Forrest snapped on as he went on stage. I went on stage right back of him–and he stopped short in the middle of a speech. He looked at me in a way that made my knees knock together, and then fairly yelled at me, ‘How dare you come on this stage during a rehearsal? How dare you put your foot on it?’

“I swear that he terrified me so I couldn’t open my mouth; or rather I couldn’t close it, for my mouth was so wide open I must have looked to him as if I was going to die of fright the next second.

“He took one step toward me and shook me by the shoulders, ‘Did you hear me?’ he thundered.

“Then I got my breath. ‘These are new handcuffs,’ I stammered, ‘and I want to show the two soldiers here how to take them off of you. If I didn’t show them, you’d be walking around all day and all to-night with the chains on you. That’s why I came on stage.’

“‘Well, show them, and get into the wings quick!’ he said. ‘Show me too,’ he added, ‘in case they forget to-night. Then off stage with you–and be quick about it too!’

…

The Cradle of Genius

“I don’t think Hoffner knows that Forrest made his first professional appearance in this theater,” said Manager Howe: “for the date was considerably before Hoffner’s time. But from the records in my office–and, by the way, they’re locked in the desk that Charlotte Cushman owned and used when she managed the Walnut in 1843–from the records there Forrest made his first appearance on any stage at the Walnut on the night of November 2, 1820. He appeared as Young Norval in ‘Douglas.’

“Edmund Kean made his first American appearance at the Walnut on December 4 of the same year. In fact, the Walnut has been the cradle of many an actor’s creeping genius and the birthplace of many dramas that became famous. Verdi’s music was first heard in America at the Walnut. Joseph Jefferson made his first Philadelphia appearance as Rip Van Winkle here; Mary Anderson’s Philadelphia début was at the Walnut. And the old time actors and actresses who, by reason of the things they’ve touched and used, which now litter up this old proproom to help make it famous–well, in addition to those to whom Hoffner has paid tribute, I can mention Macready, McCullough, Edwin Adams, James Hackett (father of the present star), E.L. Davenport, Lawrence Barrett, Modjeska, Rhea, Adelaide Neilson, Fanny Davenport, John T. Raymond, W.J. Florence, J.K. Emmett, John S. Clarke, Maggie Mitchell, Annie Pixley, Lotta–well, almost every actor and actress of prominence in the last one hundred years. In little things, perhaps, they have left their impress on this old dusty room.”

When Perry Couldn’t Appear

Hoffner’s eyes were roving. “See that spinning wheel?” he asked. “We used that in ‘Faust.’ J.B. Roberts played Mephisto, and I think it was a Miss Duffy who was the Marguerite. Harry Perry, a well known and popular actor in those days, was to play Faust.

“Well, at six o’clock in the evening he was so drunk he couldn’t stand up in the dressing room; so at seven o’clock, when we were ready to ring up, the stage manager, a man named Keefe from Boston, went before the curtain and told the audience that Perry couldn’t appear, and that he, Keefe, would play Faust.

“Well, you never heard such a hubbub! The audiences in those days weren’t very keen on excuses, and this audience catcalled and stamped and raised merry Ned. They wanted to know why Perry couldn’t appear, and Keefe told them. Then they wanted him to let Perry play Faust anyway, even if he was drunk. Keefe told them he wouldn’t stand for it, and that Perry couldn’t stand for it, or stand for anything, he was so drunk.

“Then the audience laughed, and Keefe went back, made up as Faust, and played the part. That’s the spinning wheel used by Marguerite that night,” and he jerked his head over to the corner.

…

A little later he closed the door of the old proproom. He closed it gently–very, very gently–as one closes a door when coming from a room where some one is sleeping.