FordsTowel has an interesting has some tips on making stage props. Rather than a litany of construction and crafting techniques, this is a guide for what props need to do, and how you can go about doing it.

Mary Robinette Kowal

Mary Robinette Kowal is a puppeteer and science-fiction writer in New York City. She is also works in props. Her blog contains the occasional post about the interesting props she’s built, and fascinating stories about the day-to-day life of a NYC props master (such as getting a moose-head down five flights of stairs, or carrying an axe on the subway).

You can quickly peruse all the posts dealing with props. Be sure to look at all the pages, as there’s quite a bit of great information there.

RAC Props

RAC Props is a website and online magazine run by Richard A. Coyle. Mr. Coyle has made props for Star Trek II, IV, V and VI, as well as Star Trek: The Next Generation.

The magazine has a wealth of articles on props, written by Coyle and others. Some highlights include

- The first Star Trek phasers

- The secret world of the Alex Mack prop guy

- A collectors’ guide to hand props

- A look at the Star Trek communicators

- The guts of two working Tribbles

It’s an interesting mix of original prop making and fan replica prop making.

The Property-Man in Vaudeville Theatre

The Property-man

(from The vaudeville theatre, building, operation, management, by Edward Renton, 1918)

“Resourcefulness” should be the middle name of the individual who is competent to occupy the position of property-man in a theatre. There are other important qualifications, but this one is essential. He may be called upon to supply anything from an Egyptian mummy to a three week-old child, upon a moment’s notice. He must be a bit of a carpenter, something of an artist, a great deal of a diplomat, and he must be “on the job” from the rising of the sun to considerably after the setting thereof-in other words, this is not the place for a lazy or a shiftless man.

A property-man should have the ability to meet people pleasantly and to make a favorable impression. He should cultivate cordial relations with transfer companies, with the various merchants of the city, and with other persons from whom he is likely to need favors in the way of borrowed properties. He will be faced with the necessity of requesting loans from homes, pawn-shops, museums and other public institutions, stores and individuals. He should be able to convey the impression of responsibility- and should live up to it. To a peculiar degree, he has the reputation of the theatre in his keeping; it is absolutely essential that he call for properties loaned or rented at the time agreed upon, that he care for such articles most assiduously while they are being used and that

he return them promptly and in the same condition as when borrowed.

Ancient Greek Theatre Props

How were props used in Ancient Greek theatre? How were props made or acquired in Ancient Greek theatre? Here is a brief introduction, and also some resources to help you explore further if you wish.

The presence of props in Ancient Greek theatre

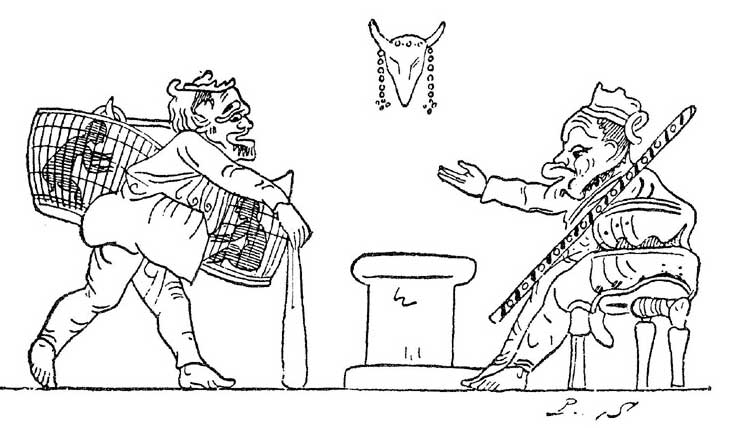

In the picture above, the actors have furniture, hand props and crowns. There also appears to be set dressing. You can see more images showing Greek theatre in action (scroll down about halfway through the page).

One of the most popular acting anecdotes involves a Greek actor named Polus. The tale was first recounted by Aulus Gellius:

Being at this time to act the Electra of Sophocles at Athens, it was his part to carry an urn as containing the bones of Orestes. The argument of the fable is so imagined, that Electra, who is presumed to carry the relics of her brother, laments and commiserates his end, who is believed to have died a violent death. Polus therefore, clad in the mourning habit of Electra, took from the tomb the bones and urn of his son, and as if embracing Orestes, filled the place, not with the image and imitation, but with the sighs and lamentations of unfeigned sorrow. (The Attic Nights of Aulus Gellius, pg. 68)

Though this anecdote is often used when talking about acting methods, it is also an interesting prop story.

Aristotle spoke of the opsis as one of the elements of tragedy. Opsis is the visual spectacle, which in Greek theatre includes the masks, scenery, costumes, and props. In Aristotle’s Poetics, he writes:

The decoration has, also, a great effect; but, of all the parts, is most foreign to the art. For the power of Tragedy is felt without representation, and actors ; and the beauty of the decorations depends more on the art of the mechanic, than on that of the poet. (The Poetics of Aristotle, translated by Twining, 1851, pg. 14)

Here, opsis is translated as “decoration.” “Mechanic” is how Twining has translated skeuopoios. Other translaters have described it as “stage machinist”, “costumer”, “stage manager”, “property man”, or “stage carpenter”.

How props were made or acquired in Ancient Greek theatre

Skeuopoios might be defined as a mask-maker, prop-maker, prop manager, or all of the above. Skeue may mean the trappings of an actor, such as equipment, attire, or apparel. Greek theatre used a lot of masks. These were impermanent objects, made of linen, wood or leather, and often included animal or human hair. This was probably the major job of the skeuopoios. If we think in terms of how theatre works today, we can imagine that the skeuopoios would have made other impermanent objects for the theatre. After all, if the theatre hired him to make masks, and they needed another object which could be made with the same skill sets, it would not make sense for them to seek out and hire another craftsman.

Perhaps the most comprehensive look at the economic and practical realities of ancient Greek theatre can be found in Peter Wilson’s The Athenian Institution of the Khoregia. In it, he describes the Khoregia, which was the cultural institution in Athens which produced the festivals, plays, and other performances featuring singing and dancing.

A khoregia will thus have brought the khoregos or his deputies into contact with a number of craftsmen. There is the skeuopoios or maskmaker. He may have also been the person who manufactured special theatrical clothing and other properties. Perhaps, as in Demosthenes’ case, a goldsmith for crowns, and even for gold-weave fabrics, will have been consulted. A less zealous khoregos could, we are told, visit the himatiomisthotes and hire second-hand costumes from him: even the scanty evidence at our disposal reveals the considerable range open to a khoregos to demonstrate his munificence or otherwise. (The Athenian Institution of the Khoregia, pp. 86-87)

J. Michael Walton posits that a number of people made all or part of their living off of theatre. Among these, he lists

…crane-operator (mêchanopoios), mask-maker (skeuopoios), costumier (himatiomisthês)… (The Cambridge Companion to Greek and Roman Theatre, pg. 288)

From this, we can see some of the specialization which exists in theatre today.

Unfortunately, none of the masks from Ancient Greek Theatre have survived today. The only visual evidence of masks and props are from vase paintings and sculptures.