The elevator music is pretty horrible, but this video of the Universal Studios prop rental house makes our East Coast rental facilities look pale in comparison.

Prop Makers Must Know a Lot

The following comes from a newspaper article about the property shop of E. L. Morse on Twenty-ninth Street in New York City. The article first appeared in The New York Times on May 8, 1904, and Mr. Morse property shop is long gone.

Maker Must Know a Lot

Any one who thinks the making of properties requires only mechanical skill is vastly wrong. The artisan must know much about the art and customs of the time in which the action of the play takes place. If the scene is in Venice, he must not make a vase that looks as if it had come from Grand Rapids, Mich., or some other American manufacturing center. If he has to furnish to a follower of Richard Plantagenet an axe or spear it would never do to make one such as a North American Indian used on the scalps of the early settlers.

When Mr. Morse undetakes to furnish properties for a play, the book of the play is given to him, just as it is to the actor or the scenic artist. He reads not only the play itself, but any books that may gibe him information about the customs and arts of the people and times. He tries to absorb as much of the atmosphere of the play as he can before he begins work on the articles themselves. In short, he does not merely copy. He creates.

He not only molds the properties. He designs them. Before he thinks of forming the final objects he makes a miniature model of the entire scene. If a visitor once sees one of these tiny models he wonders why such things ever should be thrown away. But, as the skilled artisan has told him, they generally are tossed aside when the job for which they were made is finished.

Friday’s Rehearsal Notes

The Food Network gives some credit to the shows’ prop master (or design director). Wendy Waxman is responsible for decorating and accessorizing the sets of all the shows filmed at the Food Network’s studios at Chelsea Market.

Congressman Das Williams has introduced legislation to make flesh or proximity detection technology mandatory in all table saws sold in California after January 1, 2015. I have mixed feelings about this. I think safety is important, and I feel in a lot of situations, companies will put out unsafe products until forced otherwise; this is more true with chemicals and toxic substances. But this kind of feature on a table saw is expensive and unwieldy. The vast, vast majority of table saw accidents happen on untrained home hobbyists. [ref]Popular Woodworking analyzed the injury statistics for table saws put out by the CPSC last year.[/ref] This law would make trained users pay for a safety feature that’s more needed for untrained users. Not only that, but job site saws and contractor saws are far too small and light to utilize this technology; I’m only guessing, but I would imagine these kinds of saws are more likely to be used by home hobbyists. Why stop at the table saw? Why not legislate these features on band saws, planers and circular saws? Is it just because a table saw is statistically more dangerous? Because if we’re looking at statistics, a door causes just as many finger amputations per year as a table saw; why not require flesh detection technology on all doors? Anyway, it will be interesting to see how this plays out in the coming months.

Speaking of dangerous tools, AnnMarie Thomas makes the case to let kids use real tools to build things, and not those cheap toy versions. She mentions how an engineering professor asked his class of 35 first-year students whether anyone had ever used a drill press before, and not a single hand was raised. Looks like props people are single-handedly preserving manual-arts training in higher education. Maybe if kids were taught to use tools, we wouldn’t have so many table saw accidents (the majority of which are sustained by men in their 50s; age does not make one safer, only training does).

I’ve wanted something like this for awhile, but never actually sat down to plan one out. But this adjustable sanding jig for a disc sander looks like it’s the perfect design.

The Studio Creations website has a nice tutorial on vacuum forming plastic. Don’t have a vacuum forming table? No, problem, they have a tutorial on how to build one of those as well.

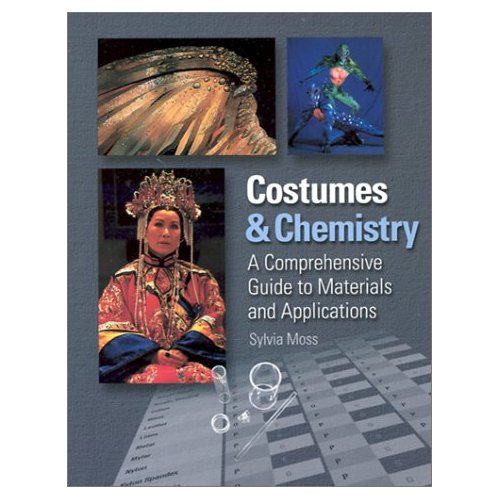

Review: Costumes and Chemistry by Silvia Moss

I only recently came across this book for the first time. I’ve never noticed it before because of the title; if I had seen it before, I would have assumed it dealt only with costumes, not props, and I would have moved right along. Make no mistake though, this book is vital to the props maker. It actually contains almost nothing about making clothes or fitting actors or even that much about fabrics and sewing. Instead, Costumes & Chemistry: A Comprehensive Guide to Materials and Applications, by Silvia Moss, covers all sorts of paints, adhesives, and plastics (in both sheet and casting form) which the prop shop uses. Though the examples shown are mostly costume props and accessories and giant character heads and suits, you can very easily apply it to many of the props you need to build.

Costumes & Chemistry reveals a lot of research and development. It turns costume crafts and props into more of a science where the materials are thoroughly tested and described, rather than a hodge-podge of traditions and assumptions swirling around in each person’s head. Moss talked with chemists, technicians, salespeople and manufacturers of many of the materials you use from basically every company you’ve ever heard of who makes these materials. Armed with a number of grants from UCLA and interviews with so many people working in the field, she has created a reference book that should be on the shelf of anyone working in props and costume crafts, as well as those interested in cosplay and convention costumes, replica prop making, LARP, and even model making.

Part 1 of the book is brief, providing much of the same safety information found in Monona Rossol’s book. The bulk of the book is divided between parts 2 and 3, or materials and applications.

The section on materials divides them into categories such as paints, adhesives, plastic sheets, and thermoform plastics. For each type of material in these categories, Moss gives the brand names of the various products that she tested, examples of why and how they are used, a description of the physical properties, how to clean them up (where applicable), precautions and health and safety information, where to buy them, and what sizes and forms they come in. This isn’t where you will find information about making props from paper plates and pipe cleaners; this covers all the modern materials you’ve used or read about such as Sintra, latex foam, leather dye, Kydex, etc.

In the section on applications, Moss breaks down how many example costumes were made. These include costume accessories, headpieces and jewelry from Las Vegas revues, Broadway musicals, advertising characters in commercials, various mascots, and other venues. This section provides some illustrations giving general techniques, but for the most part, it discusses the applications of various materials through very specific examples from a wide variety of craftspeople. Some of the pieces chosen for the book are quite recognizable, and it can be interesting and surprising once you find out what materials and techniques were used to create their look.

Costumes & Chemistry was published in 2004, so it should remain up to date for awhile. I could see an update in a few years to include new formulations of current materials and new brands (as well as the deletion of defunct brands; Phlex-Glu, for example, is listed in the book but no longer produced). For the most part though, most of these materials have been in use for several decades now, and barring some dramatic new invention, should remain in use for several decades more.

Weapon Safety is Nothing New

As a reminder that accidents with stage weapons are nothing new, I have two brief stories of mishaps from over a century ago. The first comes from The San Francisco Call, September 27, 1896:

A few weeks ago a tragic accident happened in London. The actors had to fight a duel on the mimic stage. They did not rehearse with swords, but on the night of the first performance the property-man gave them their weapons, which they used so realistically that the delighted audience wanted to give a recall. Rounds of applause came again and again, but the man who had fallen did not get up and bow before the footlights as dead actors are in the habit of doing. He was dead in real earnest, killed by a thrust of his comrade’s sword. When the horrible truth dawned upon his comrades the curtain was lowered and the audience dismissed from the play, which had ended in an unrehearsed tragedy. The next day the papers were full of lamentations over the sad event and blame was given to the management for the carelessness which had permitted sharp swords to be used without first testing them thoroughly at rehearsal.

No training, no rehearsal, weapons that should have been dulled… these are the exact same reasons accidents happen today. Â This isn’t new technology or unknown knowledge; we know, and have known for well over a hundred years how to prevent accidents from stage combat weapons, yet they still happen.

The second comes from The New York Times, September 12, 1907:

Maz Davis, 30 years old, of 434 West Thirty-eight Street, a property man for David Belasco, was injured on the right hand last night by the accidental discharge of a stage gun, the “wad” of which pierced his hand, while the powder burned both his hands and face. Just before a rehearsal of the “Girl of the Golden West,” he was examining a revolver when he accidentally pulled the trigger. He was taken to the Roosevelt Hospital.

Ouch. Remember, stage guns are still dangerous, even if they are only “blank-firing”, “powder” or “toy cap” guns.