The following is one of several interviews conducted by students of Ron DeMarco’s properties class at Emerson College.

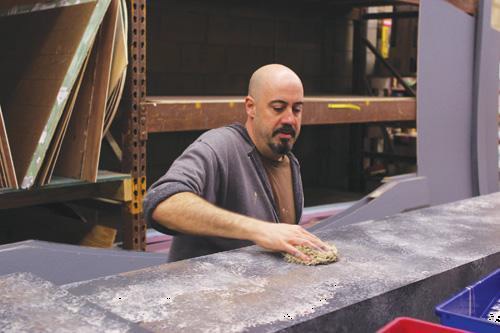

J. Kenneth Barnett III

By Rachel Hunsinger, Theater Education class of ’18 Emerson College

J Kenneth Barnett III is currently the Resident Scenic designer, Scenic Artist, and Properties Master for Charleston Stage. He resides in Charleston, South Carolina with his wife Ann and son Sammy. But before he made his way into the city he hopes to live out the rest of his days in, he grew up in Rockford, IL. Even at a young age he was bit by the art bug. Ever since he could remember he enjoyed painting or drawing. His artistic interests flourished as he aged, and he eventually took his first steps into theater. In the sixth grade he was in his first play about the great George Washington. He played the villain, King George, and continued on to go to a performing arts school from seventh to twelfth grade. Out of all the arts offered there though, “art and theater were [his] favorites.”

He continued on to pursue his theatrical passion at Eastern Illinois University in Charleston, IL. There, he completed his B.A. in theater with a minor in Art with a TSA scholarship that covered his tuition. He studied as an actor but worked in the shop (building and painting scenery) as a part of his scholarship.

After completing his college education, Barnett immediately took his first job at the New American Theater. There, he started as Prop Master, doing typical prop work and sometimes worked as a carpenter. But he later became not only their Scenic Artist but also their Resident Scenic Designer. When asked why he chose to end his acting career and instead follow his technical theater passions Barnett responded: “I like being an actor, but I don’t like to be around them all the time.” He went on to explain that resident and equity actors he had worked with only wanted to talk about theater –nothing else — and that the last thing he wanted to talk about at the end of a hard day at the theater was more theater.

But he did recognize the fact that being an actor got his foot in the door for many opportunities regarding technical theater. The connections he made performing led to greater relationships in the theater world. One of the most influential technical theater collaborators he ever worked with was an incredible Chicago designer by the name of Michael Philippi. A Tony award winner and well renowned designer, Philippi was a very respected man in the business. As described by Barnett be was a bit of a “hard ass.” When they first met, Barnett was a young “snot ass kid” as he describes himself, and Philippi pushed him very hard. But in the end they formed a very mutually respectful relationship as they worked together. Philippi was an incredible painter, but would even eventually praise the work of his prodigy. When Barnett was settled in at Charleston Stage, Philippi visited and proudly told his friends bosses let him paint everything.

The moment Barnett felt like he earned his friend’s respect was during a production of Dracula. Barnett was head of the props for the show and had found a working prop that he decided would just be used as set dressing, nothing more than for show and not used as if it functioned. Philippi disagreed, and the two men argued back and forth until Barnett proudly pronounced that he would cut the prop if challenged again on his choice. Philippi didn’t back down, and so the prop master cut the object from the show. Barnett soon after realized how much he thought he had disrespected the man and receded into hysterics to the costume designer and stage manager reciting “I’m going to get fired.” The next day he returned to the show, encountered Philippi, and was received with an ongoing respect from his mentor from then on.

Sadly Michael Philippi passed away five years ago from a heart attack while walking to theater for tech. Barnett recalls the time of his friend’s death as a shock, and that the world had lost another great man too early. As well as Philippi, Barnett has had the pleasure of working with many people he has found to be great inspirations and companions such as J. R. Sullivan (Artistic Director and Founder of the New American Theater) and Jon Accardo (Costume Designer).

As Ken Barnett has continued throughout his life, he has always wanted to stay in theater. According to him he’s just simply “done it for so long.” It started as a seasonal job at first, and then he would work part time in the summer doing house jobs such as house painting. But he always came back to the theater, and was always happy to return for it. Throughout the changes of location and company of where he worked in props and design he always found a way to integrate his own personal process.

He describes the beginnings of a show’s prop component to really begin with meeting with the director, making a prop list, and then going shopping, borrowing, or constructing the prop. Nowadays he sees the prop finding process to be way less of a hassle. The internet has changed the way he has been able to obtain props and also to do research to begin his list. Back then, he would have to go to the library and spend hours rummaging through books of time periods or conceptual ideas or references found in scripts. Not only would he have to rummage through the library, but also carry the last collections of books he needed back and forth with him. And designers even couldn’t just simply email him their ideas, they had to be black and white xerox memos.

Once the time and effort was put into making the list, he had to go out and find the places he could possibly retrieve what he needed. That included driving all around and taking expensive polaroid pictures of everything he found, taking the pictures back to the director to see if they liked it and then driving back to purchase what he needed. Now Barnett cannot imagine his prop life without his smart phone.

“There’s a lot weirder stuff now,” Barnett comments about today’s prop world. He recalls needing a sarcophagus early on in his career for a show and having to make one using styrofoam and a hot wire cutter. More recently he needed the same prop but was able to find a CD holder made in the shape of a sarcophagus and just had to modify it. He enjoys the fact that today’s world is really just filled with a lot more ‘things’. He loves that Halloween is a lot more popular now, and instead of making brains he can pick some up at the store. The same goes for Christmas, and everything else because, he says, “the demand for stuff is bigger now.”

Even though the props have become more readily available, Barnett still thinks a good props person should have a good eye for detail. As he puts it, “The ability to look at one thing and see how it could be changed into something else… A good prop person has a good eye for looking at something and knowing what it needs to look like when it’s done. Good artists say in their head ‘I can make it work.'”

Being a smart propper is still important no matter how much easier it has become to get the prop. Barnett definitely values a prop master who has a good understanding of many different aspects of technical theater such as upholstery, sewing, sculpting, and painting skills. But all in all, a good prop person must understand what the show needs, while keeping it under budget. A designer or director might not like something, so Barnett chooses to say “I can get you this or this but not the exact thing you want… but it’s free.” The best moments to Barnett come when when everything comes together (props, costumes, sets, lights) and a new, magical environment is created. And because of hard work and finding what you need, Barnett says the experience is golden. “When the props you found are shown onstage, the appreciation of it varies but you know you put hard work into it and that’s all that matters.”

Currently, Barnett has taken his talents to the regional theater company CharlestonStage, along with his technical theater partner in crime for 20 years, Paul Hartmann. To him, “Charleston Stage is a different beast.” The company puts on nine to ten shows in the span of nine months. To him, the time difference is the big thing, so there’s not a lot of room for error. If someone is sick or something, tough luck because the schedule is so tight. What also even further squeezes the time management is the fact that the theater the company works out of shares its space with many other arts events in the city. Things have to be taken down and set up, back to back, with and without overlap. Once you’re thrown into the workings of the company, as said by Barnett, “it’s a roller coaster.”

Charleston Stage also has a high school technical theater apprenticeship program called “TheaterWings” in which students from ninth through twelfth grades are given hands on technical theater training in the scene shop, costume shop, and work as stagehands, assistant stage managers, or stage managers. Since joining the company, Barnett has taught students in the scene shop about technical techniques and ongoing theater skills he has picked up in the business. “It’s hard work” he says regarding the efforts students must put into the program, “It’s serious, and it happens fast.”

He loves that the program teaches kids about pulling their own weight, not just in the theater world, but also in real life. To him, it gives these kids major responsibilities. They learn that if they do not pull their own weight, the entire show stops but as long as they work as a team and make sure every member is putting in a lot of effort, they can’t fail. His favorite lesson to teach is that theater is a collaborative effort; he loves it because he can trust the people he works with to do their job because they love it just as much as he does. To him, that’s what makes it fun.

Back at the New American Theater, he works with students in a similar program — they also run shows and work in the shop. Recently, one of his students from the program named Sean contacted him on Facebook. Sean had gone on to be a technical director at a big theater company in Chicago but later quit his job to earn a master’s degree at Yale in technical theater. As a young sixteen year old, Sean would jokingly hound Barnett for a beer many times while they worked on a set or painted a drop. He contacted Barnett to thank him many times over for the great teachings he bestowed upon him that later led him to a rich career in technical theater. Barnett responded by promising that if Sean visited him in Charleston, he would be sure to buy him a beer this time.

When asked whether or not he would stay in his current career placement Barnett responded, “I like it here and designing, I like the people I work with, the wings kids, everyone. I love Charleston and want to stay. I could see myself doing this till the day I die.”

From personal experience being a wings student under Ken Barnett, all I can say is that Charleston Stage is lucky to have such a dedicated theater artist. He has done momentous work in all the shows he’s contributed on while he has been at the company, and I cannot wait to see the continued amazing work to come.