The title of “prop designer” seems to appear more now than in the past. More experienced prop masters have made note that younger props people are being credited as prop designer on their shows, or self-identifying as one on their resumes. Is this just a trick of perception, or are prop designers actually growing in number?

First, some background: most theatrical shows will have a props master who supplies all the props. The title may vary (see my previous article on “prop master versus props director“) but the duties remain the same. A resident theater typically has a full-time prop master on staff, while smaller and ad hoc groups will hire a prop master on a show-by-show basis.

The scenic designer supplies the prop master with the design of all the props, whether that means scale drafting, quick sketches, research images, or simple verbal descriptions. A prop master often has to “fill in the gaps” of the scenic design, particularly with small details and set dressing, and thus brings a designer’s eye to the production. In the most successful relationships, the scenic designer and prop master are true collaborators.

So what then is a prop designer? The debate rages on about the appropriateness of that title, so I will not rehash any of that here. Again, this is a post about the prevalence of the term.

United Scenic Artists (USA 829) is the union which covers designers and scenic artists working in the US on film, theatre, television, opera, dance, commercials, and more. As far as I can tell, they do not have prop design as a membership category. You do not see anyone credited as prop designer in LORT theaters or Broadway shows, or on major films and television shows. None of the awards for theater in any major region recognize prop designers on a regular basis.

Instead, you find the term used in smaller settings, such as Off-Broadway, Chicago storefront theatres, and in university theaters. These are companies which may not have a full production staff and which may use non-union designers and technicians.

Luckily for us, the records for Off-Broadway productions are available in a number of easily-searched databases. The Lortel Archives purports to have records for every show ever produced Off-Broadway since 1952. This gives us a fairly complete record of all theatrical activity in a distinct area over several decades. We can use it to see how the title of “prop designer” has changed over time.

Of the 6,334 productions in their database, they have 157 prop designers credited on 149 shows (some shows have multiple prop designers).

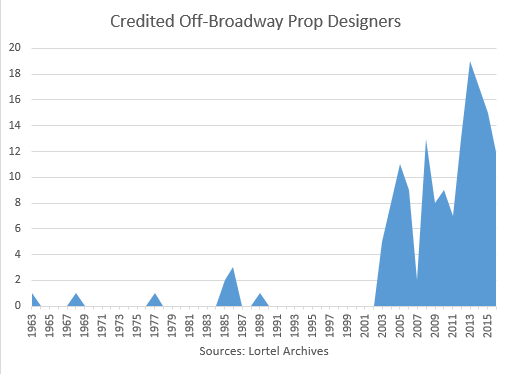

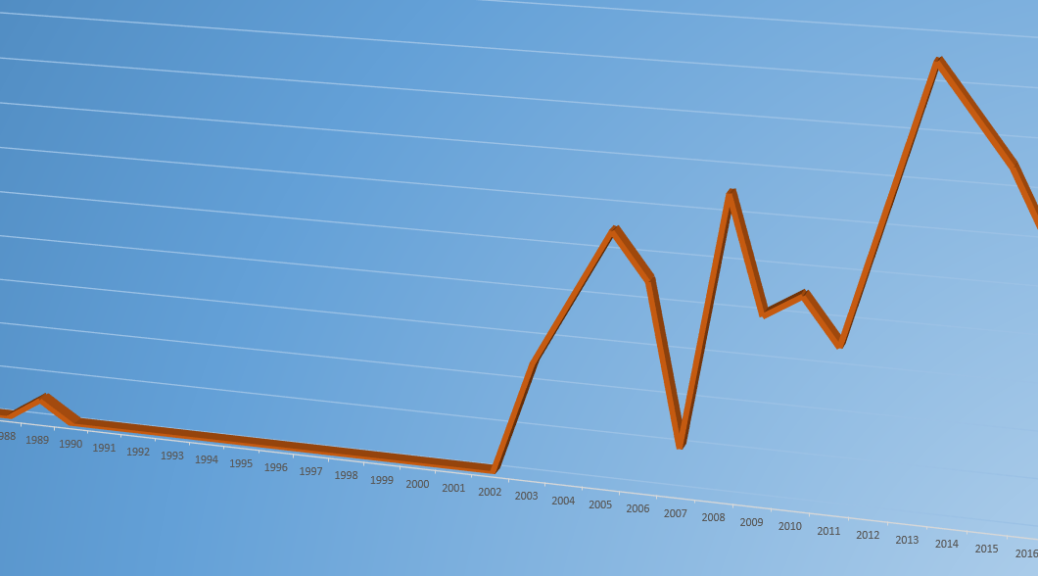

The first thing I did was look at how many prop designer credits appeared per year. I charted the results out in the graph below.

You can see a few scattered credits starting in 1963, but the real explosion happened in 2003. The highest peak occurred in 2013; most of that is because a single show, The (curious case of the) Watson Intelligence, had four prop designers. It appears to be an upward trend at the moment; we need more time to see whether it will plateau at a certain point.

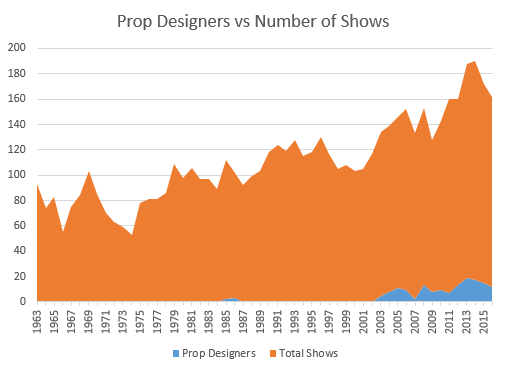

I next looked at whether this increase in prop designers could be attributed to any sort of general increase in the number of Off-Broadway shows being produced. I overlaid the amount of prop designer credits with the total number of shows per year listed in the Lortel Archives.

You can clearly see a general upward trend in the number of shows being produced. Other than in 2009, during the height of the Great Recession, the 2000s have consistently seen more shows than even the highest point in the 1990s.

My hypothesis is that with so many shows and a limited supply of props people, producers were looking for ways to sweeten the pot without paying more money (at least up front). Offering credit as a “props designer” is one such way. Besides increased visibility and recognition for the props person, it opens up the opportunity for residual payments if the show tours or has a long life. Once a few people started receiving credit, the flood gates were opened, and more and more props people were demanding it.

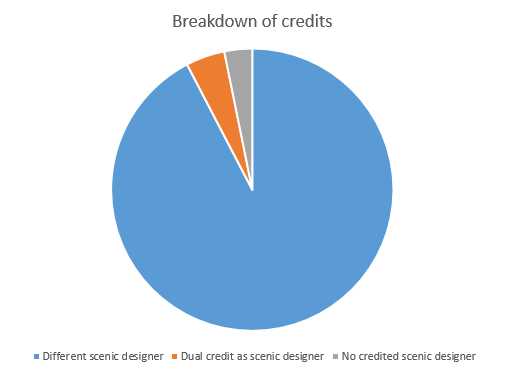

The final bit of data I looked at was whether a scenic designer was also credited with the props designer. In some shows, one person is the scenic designer while another person is the prop designer. In other shows, a single person will be credited as both the scenic designer and the prop designer. Finally, you can have a show with a prop designer but no scenic designer credited.

You can see that an overwhelming number of shows with a prop designer (92%) have another person credited as the scenic designer. Seven shows give scenic design and prop design credits to the same person, while five shows have a prop designer without a scenic designer.

In Off-Broadway theater, the use of the term “prop designer” has been on the rise since the turn of the millennium. If we have data for other regions of theater, I am sure we will find a similar trend. As an industry, we need to acknowledge this and determine what to do with it. I think the first step is clarifying what exactly a prop designer is, and how they differ from a scenic designer and prop master. We cannot keep ignoring it.

To me I dont think of it as unsual at all. I’m 20 now and By the time I had a heavy interest in props around 2012 the term was everywhere. I think it’s not too hard to imagine what a prop designer would do either. I know in theater props can range from chairs to statues to swords. But I’ve always thought of that as set dressing, something more for the Scenic Designer to design. It seems to me that props that must be handled by the actors, Such as pipes with fake smoke, Guns, Puppeteer Animals. All require a more distinct skill set than set dressings. From those I know who call themselfs prop designers, they handle things the actors handle, while a props master would oversee everything physically on the stage, tables, lamps, Ect. Also, Friends who Call themselfs prop designers often work extremely closely with the costume designers. For example, is Iron Mans Helmet a prop? or costume? Most of my friends do film work not theater work so that too may be a difference.

After leaving school in 2003 the first job I landed in props would fall under “props designer.” Unlike any examples in school, at this theatre the scenic designer had no hand in designing the props for the show. They were developed, designed and built completely separately. In this case, I feel Props Designer is appropriate. (Though I still think it’s an odd way to do things.)

I have seen a lot of set designers just out white models without furnature drawings or research at all. On the other hand you also have old school designers who draw every detail and molding number as well as cabinet hardware. So it really depends. Thank you so much for all the insight and research Mr.Hart.

Thank you Eric. I am the first to want full and clear credits for all concerned on a show. If I see a beautiful puppet in an otherwise puppet-free show I would love to see that Puppet Design credit clearly stated. But unfortunately it is the regular case that small companies decide they cannot afford to contract a Set Designer; however they cannot manage to stage the show without clothes and chairs. And so in the end a printed program credits a Costume Designer and a Prop Designer. In fact neither individual may have the right to claim such precious titles. Costumes supplied by, Prop Director, special prop construction, Prop Artisan, Prop Shopper, there are so many respectful ways to credit such work without inferring that these are fully trained and experienced Designers. My Union Scenic Design contracts stipulate responsibility for show prop design. How can it then be respectful or comprehensible for the program to print some other person’s name as Prop Designer in the show program? It is not OK. It is incorrect, confusing and disrespectful. And it infers an equality of responsibility that is completely untrue. This an insidious problem that needs a public debate to resolve it.

Thanks Eric for your info. I am a novice prop person for a local community theatre at a 55 year old senior community in Gold Canyon, AZ. We are doing the play You Can’t Take It With You. We have virtually no budget for props. As you probably know, this play has an incredible amount of props. I am wondering if you have any ideas on how to make a baked goose, blintzes, a skull ashtray, 1940s period phone, or any other props needed. Any assistance that you can give me would be greatly appreciated.. Thank you, Becky Anderson