What is Celastic?

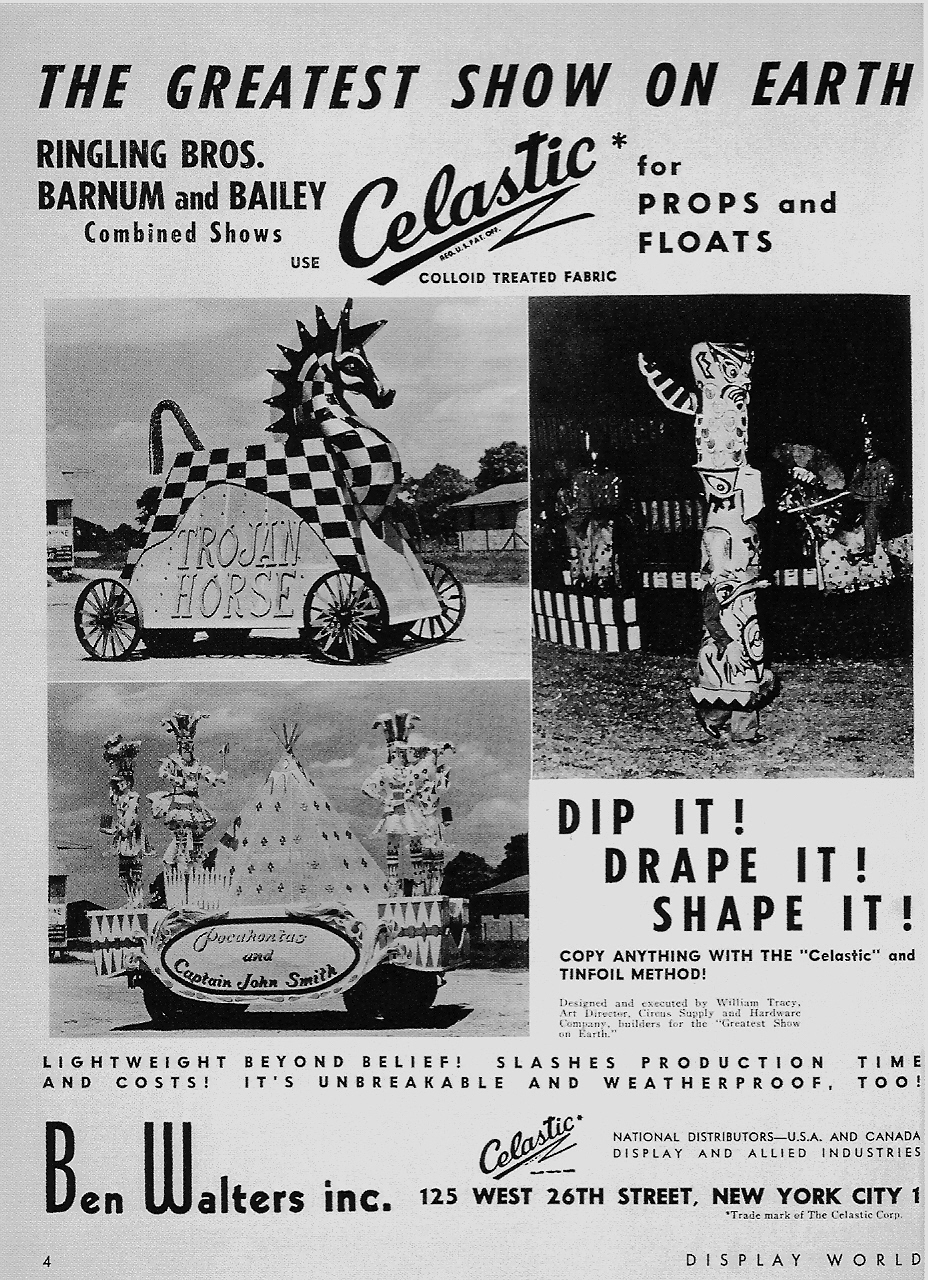

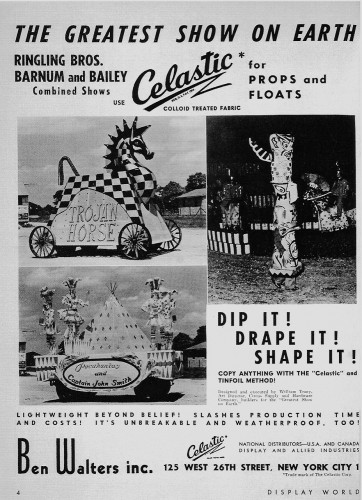

Celastic was first trademarked in 1926. It was being used by the theatrical industry as early as the 1930s, and saw its most widespread use in theatres of all sizes by the 1950s. It appears to be one of the most popular prop-making materials of the ’70s and ’80s, and why not? It was used to make everything from masks to armor, statues to helmets. It reinforced other props, or simply gave them a smooth, flowing surface.

Celastic is a plastic-impregnated fabric which is softened with a solvent such as acetone or MEK. When it is soft, it can be manipulated into nearly any shape; it can be wrapped around forms, pushed into molds, or draped over statutes. You can cut it into strips or small pieces; Celastic adheres to itself. When it dries, it becomes hard again, thus retaining whatever shape you can manipulate it into. If necessary, it can be resoftened and further manipulated.

Here is an example of what passed for safety knowledge back when the use of Celastic was prevalent: “Rubber gloves should be used to keep the Softener off the hands. The liquid is not injurious under normal working conditions… Common-sense precautions will make the medium acceptable for any school use” (Here’s How by Herbert V. Hake, 1958). Of course, “not injurious” is not the same as “harmless”.

Acetone and MEK of course can be absorbed through the skin, and the fumes can cause neurological damage. As prop makers became more health-conscious and aware of the effects that cumulative exposure to solvents, especially strong ones like MEK, could have on their bodies, they began seeking out alternatives and scaling back the use of Celastic. Today, you’d be hard-pressed to find even a single practitioner using this material. You find one occasionally; their argument is that no other material can be draped as finely as Celastic, and if you take the proper precautions, you can protect yourself. There is some point to that; all chemicals can harm your body to some extent, and you need to be aware of how that chemical can enter your body, how much is entering it, and how to properly limit your exposure to it. If you wear the proper gloves and sleeves, respirator, goggles and face shield, and work with the solvents in a well-ventilated area (preferably some kind of spray booth or hood), working with Celastic would be no more dangerous than working with wood.

Of course, we rarely work alone in theatre; if one person is working with Celastic, than everyone is breathing the fumes. Prop shops are rarely the best ventilated areas, so the vapors can hang around long after everyone has removed their respirators. And of course with all the deadlines and time pressures, the temptation to take shortcuts in safety are always present; “I’ll just dip this one piece in Celastic really quickly; I don’t need to go all the way to my locker to get my respirator.”

Most prop shops these days seek to use the “least toxic alternative.” Whatever perceived benefits Celastic may have is far outweighed by the existence of less toxic materials that will accomplish the same goals.

Some of these alternatives are thermoform plastics which are softened by mild heat; they can be dipped in boiling water or blown with a hot air gun. One of the first to be introduced was known as Hexcelite; it was developed as an alternative to plaster for setting broken bones in a cast. Today, it is sold under the trade name of Varaform. Two other popular brands are Wonderflex and Fosshape. Wonderflex is a hard plastic sheet, while Fosshape is more of a plastic-impregnated fabric.