The following comes from the Foreword to a book on amateur theatricals published in 1904:

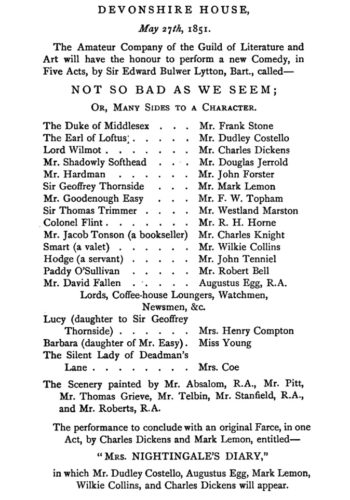

Amongst the many extraordinary amateurs who have from time to time appeared prominently before the public, the most remarkable was Charles Dickens—remarkable because he was not only a great novelist, but because he had the true dramatic instinct in a wonderful degree, and this, combined with most unfailing energy and enthusiasm in the work, made him the wonder and admiration of all with whom he came in contact. All who ever saw Dickens act have declared that in gaining a great novelist the world lost a most accomplished actor.

He joined a dramatic club when he was serving his time in a lawyer’s office, and it is said that recognising his natural aptitude for the stage, he made up his mind to adopt it as a profession. He was untiring in his efforts, and constantly practising everything that might conduce to his advancement, even such things as walking in and out, and sitting down in a chair. Thus he studied four, five, and six hours a day, shut up in his own room, or walking about the fields.

To all would-be stage managers he is a shining example, for it was in this capacity that his talents for organisation and management were conspicuous. He writes of an early amateur performance which he arranged and conducted. “I had regular plots of the scenery made out and lists of the properties wanted, nailing them up by the prompter’s chair. Every letter there was to be delivered was written, every piece of money that had to be given provided; I prompted myself when I was not on, and when I was I made the appointed prompter my deputy.”

Amateur performances had always a wonderful fascination for him, and the record of many of the brilliant performances in which he took part will be found in Forster’s “Life of Dickens,” together with the casts of many of the plays he produced, and which contain the names of many notable men and women who have left more solid reputations behind them in other walks of life.

Neil, C. Lang. Amateur Theatricals: A Practical Guide. London: C. Arthur Pearson, 1904. Google Books. 30 Nov. 2007. Web. 5 Aug. 2009. <https://books.google.com/books?id=lB5IAAAAIAAJ>.