The following is from a newspaper column entitled, “Some Odds and Ends from Stageland’s Daily Gossip”, first published in 1903.

Some idea of the varied collection of objects which accumulate in the property room of a theatre is to be obtained from a description of the contents of the old Boston Museum property room, which will soon be scattered to the four winds. In a general way the public has learned to know that the “property man” of a theatre is one who looks after such details of the productions as concern chairs and tables, the bottles that the people pour their liquor from, and the pen and ink used by the heroine to indite her loving messages.

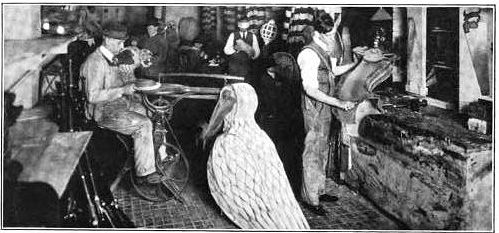

The master of properties must still be a resourceful person, but in the old days, where the frequent changes of bills necessitated additional “props” every week or so, the ingenuity of this functionary was often taxed to the utmost. The property room of the Museum is thus described in The Boston Globe:

“The apothecary’s shop in ‘Romeo and Juliet’ wasn’t a circumstance to the old property-manufacturing shop in the cellar of the Museum, where may be seen skulls and crossbones, stuffed animals of both wild and domestic species, wings for witches, angels, and decils, and other curious things that can’t be enumerated in a column. The animals, both real and of papier maché, repose on shelves all around the walls, a weird, grinning, motley troupe of once indispensable stage characters that would have brought their possessor to the stake in witchcraft days, and all destined for the dirt heap within a few days.

“There are the wolves’ heads, with gleaming teeth, fangs, and eyes, that were wont to be thrust beneath the door of the log cabin which the stout arm of Frank Mayo held in place in the thrilling honeymoon scene in ‘Davy Crockett.’ The big bellows with which Tilly Slowboy once blew the fire in ‘The Cricket on the Hearth’ hangs upon the wall, and the cradle in which she rocked the baby lies in a corner. In another corner are stacked old rusty muskets, including some flintlocks that defended the breastworks in Dr. Jones’s centennial drama, ‘The Battle of Bunker Hill’ twenty-eight years ago.

“From the centre of the ceiling, suspended by strings, hang three mangy looking stuffed animals that were once features in conveying the moral lessons taught by the waxwork tableaus, sold more that a decade ago. For sixty years these animals, a domestic cat, a dog, and a monkey, have been comrades, but they must now go the way of all else identified with the Museum.

“The cat and dog, now half hairless and showing repulsively their dried-up gums and loosened teeth, used to be pictures of ease and contentment when representing the sole objects of the affection of the old maid and the old bach in a wax tableau.

“The monkey had his mission to fill also, but what it was is now forgotten. Of late years he has hung by a movable string before the door of the property room in such a way that he would drop with a dull thud on the breast of any one entering the door, a startling experience for an unsuspecting stranger, which has contributed to the enjoyment of the property man’s life, however.

“In another part of the cellar is stored a raft of stage furniture of every kind. There are the seats of Caesar and Brutus from the Senate house, the royal chairs of Macbeth and his restless helpmeet, the big, glittering chair in which John Wilkes Booth was crowned as Richard III., and the gracefully formed mediaeval chairs in which Hamlet has oft pondered the proposition, ‘To be, or not to be.’

“There are stacks of spears and halberds and Roman standards, and a pathetic souvenir in the shape of a rude human effigy of burlap stuffed with excelsior, which is recognized as the dummy used in the burial of Ophelia, over which the Queen strews flowers and weeps and says, ‘Sweets to the sweet, fair maid.'”

From The New York Times. May 17, 1903.