The following comes from a 1916 book and describes the evolution of furniture on the theatrical stage:

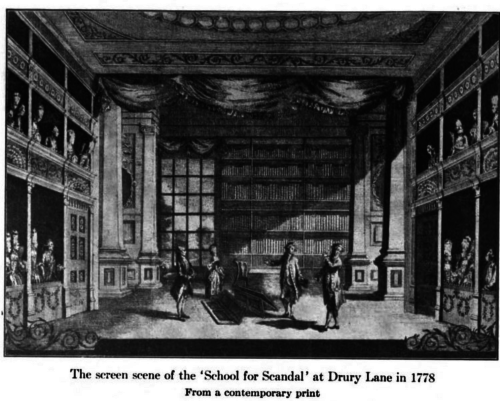

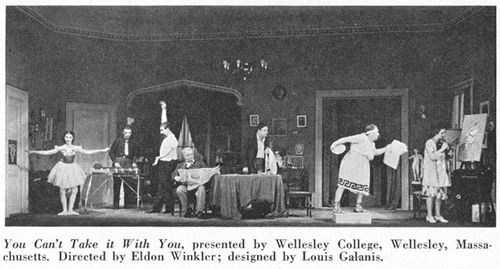

When the modern play calls for an interior this interior now takes on the semblance of an actual room. Apparently the “box set,” as it is called, the closed-in room with its walls and its ceiling, was first seen in England in 1841, when ‘London Assurance’ was produced; but very likely it had earlier made its appearance in Paris at the Gymnase. To supply a room with walls of a seeming solidity, with doors and with windows, appears natural enough to us, but it was a startling innovation fourscore years ago. When the ‘School for Scandal’ had been originally produced at Drury Lane in 1775, the library of Joseph Surface, where Lady Teazle hides behind the screen, was represented by a drop at the back, on which a window was painted, and by wings set starkly parallel to this back-drop and painted to represent columns. There were no doors; and Joseph and Charles, Sir Peter and Lady Teazle, walked on thru the openings between the wings, very much as tho they were passing thru the non-existent walls. To us, this would be shocking; but it was perfectly acceptable to English playgoers then; and to them it seemed natural, since they were familiar with no other way of getting into a room on the stage.

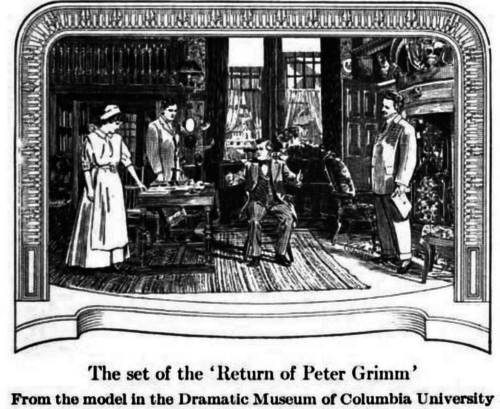

The invention of the box-set, of a room with walls and ceilings, doors and windows, led inevitably to the appropriate furnishing of this room with tangible tables and chairs. Even in the eighteenth century the stage had been very empty; it was adorned only with the furniture actually demanded by the action of the drama; and the rest of the furniture, bookcases and sideboards, chairs and tables, was frankly painted on the wings and on the back-drop by the side of the painted mantelpieces, the painted windows, and the painted doors. In the plays of the twentieth century characters sit down and change from seat to seat; but in the plays produced in England and in France before the first quarter of the nineteenth century all the actors stood all the time—or at least they were allowed to sit only under the stress of dramatic necessity—as in the fourth act of ‘Tartuffe,’ for instance. In all of Molière’s comedies there are scarcely half a dozen characters who have occasion to sit down; and this sitting-down is limited to three or four of his more than thirty pieces. Nowadays every effort is made to capture the external realities of life. Sardou was not more careful in composing his stage-settings in his fashion than was Ibsen in prescribing the scenic environment that he needed. The author’s minute descriptions of the scenes where the action of the ‘Doll’s House’ and of ‘Ghosts’ passes prove that Ibsen had visualized sharply the precise interior which was, in his mind, the only possible home for the creatures of his imagination. And Mr. Belasco has recently bestowed upon the winning personality of his ‘Peter Grimm’ the exact habitation to which that appealing creature would return in his desire to undo after death what in life he had rashly commanded.

“Evolution of Scene-Painting.â€Â A Book About the Theater, by Brander Matthews, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1916, pp. 144–146. Google Books, books.google.com/books?id=89gUAAAAYAAJ.