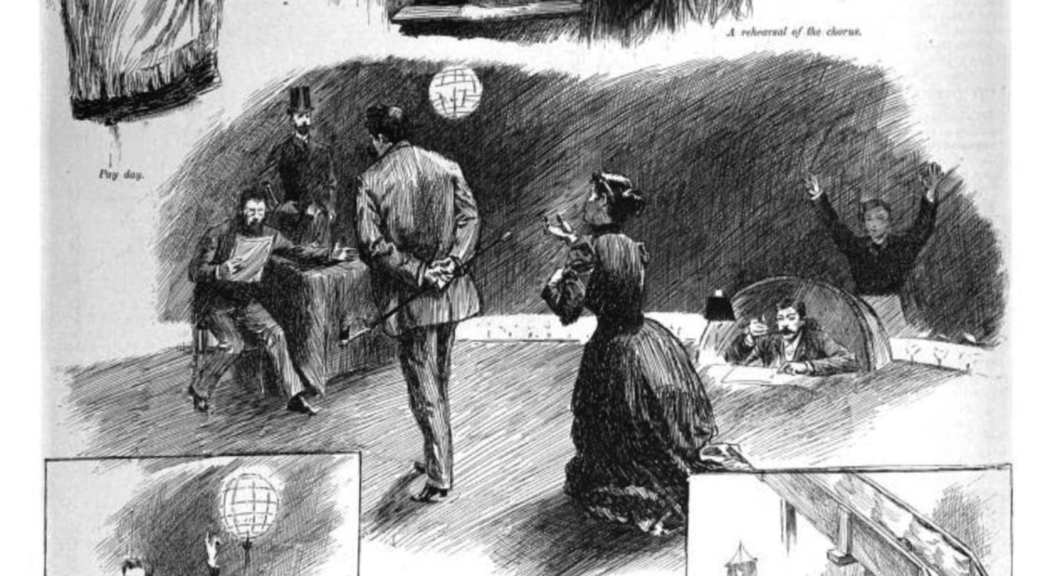

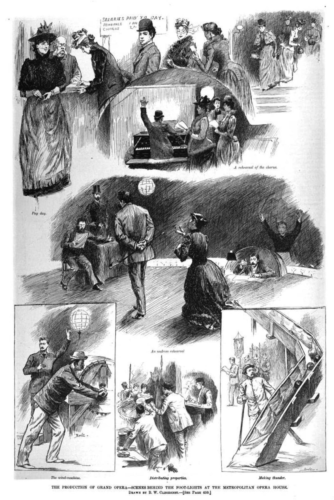

The following comes from an 1888 magazine article:

The Property-Man

The days of the property-man are passed in deceiving the public. The average theatre-goer does not always realize that he is indebted to the Master of Properties (as he is sometimes called), for many of the most striking effects on the stage. A call for the scene painter might, in justice, be equally responded to by the property-man. Being essentially a Jack-of-all-trades, he has served an apprenticeship at several vocations before drifting behind the scenes of a theatre. He is something of a carpenter, a good deal of a student, and above all an artist.

Upon the property-man rests in great part the responsibility of properly mounting a play, and from the time when the property plot is given to him he must rely on his own artistic judgment. The plot in question is a list of articles, known as properties, or “props,” which he is required to furnish. It comprises everything from a fine-tooth comb to a church organ, and he must be equal to the emergency of manufacturing any article on the schedule. To use a technical term, there is nothing in heaven or on earth that a property-man may not be required to “fake.”

A well-stocked property-man in one of our metropolitan theatres resembles nothing so much as an old-fashioned curiosity shop. As a rule, it is a long room, occupying the entire top floor of the building, with a low ceiling. In the centre of it is placed a work bench, while near by stands a baking oven. The floor is literally covered with bulky “properties,” such as a pianos, lounges, boats, pillars, trunks, ancient and modern furniture, grass mats, cradles, pulpits, coffins, etc. On the walls hang pictures, mirrors, guns, helmets, swords, shields, knapsacks, drums and cutlasses. From the ceiling dangle hats, cloaks, draperies, skipping ropes and lanterns. On every available table are placed skulls, knives, belts, speaking-tubes, baskets, plates, false teeth, vases, Indian clubs and dumb-bells. Numberless other “props” are scattered haphazard everywhere.

Papier maché is the prime factor used in the manufacture of stage properties. For instance, in making an ornamental vase, the property man first makes a clay model from which he forms a plaster cast. Into this he pastes thin layers of papier maché, and then places the vase in the oven already mentioned. When quite hard it is removed and painted, according to taste, to represent the real china article. A coat of varnish finishes the work. As a rule, furniture on the stage is nothing more than paste-board. A cannon, apparently weighing 300 tons, is made of paper, and can easily be carried by a small boy; and in many a banquet scene hungry comedians must smack their lips over a papier maché turkey.

Tin is also of great value to the Master of Properties in making theatrical armor, swords, daggers, etc. Spectacular pieces tax the ingenuity of the property-man, as he must be past-master of every trick in his trade to produce proper effects for these glittering productions.

“The Property- Man”, Hyde-Fiske. The Epoch, vol 4, no. 99. New York, December 28, 1888. pp 382-383. Google Books, accessed 10/1/20. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Epoch/jnk4AQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0