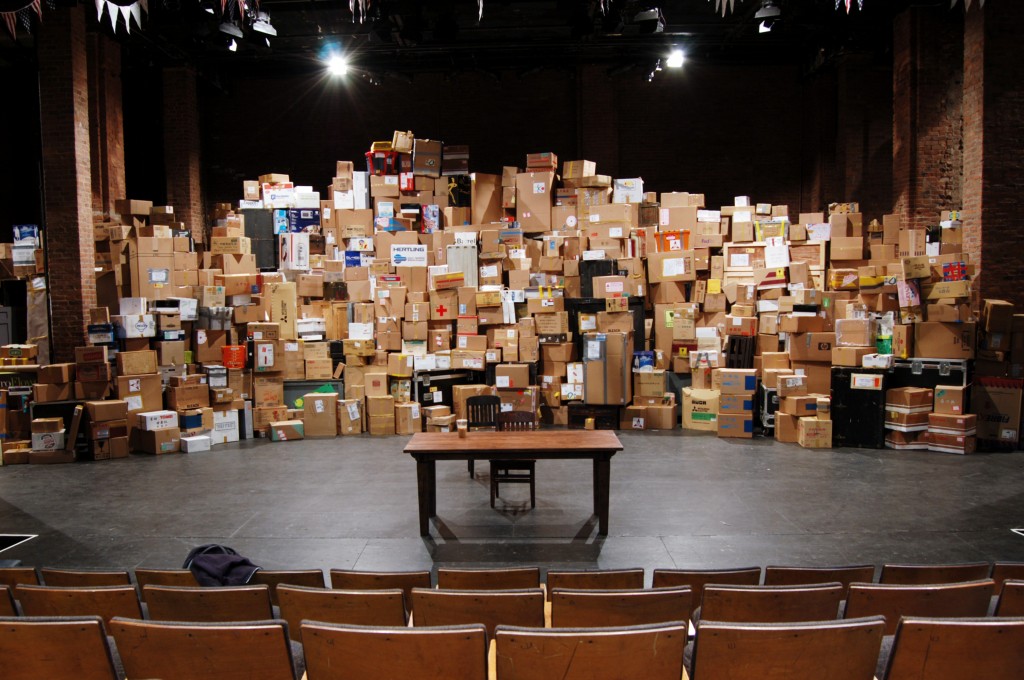

For our upcoming production of The Book of Grace by Suzan-Lori Parks at the Public Theater, we need beer. Technically, we need about ten beers per night.

Unfortunately, in most legitimate theatres, you cannot have the actors drinking beer during a performance. You need to figure out a way to have a beer can filled with water or something equally innocuous. One way to do it is by emptying a beer can and refilling it. This can be tricky if you also want to crack the lid as part of the stage action; the sound is made because the contents are under pressure, and unless you re-pressurize the can when filling it, you’ll lose that satisfying crack noise. Your other option is to cover a can of non-alcoholic liquid with another label. You can either cut the label out of a real beer can, or manufacture one out of paper. We’ll take a brief look at both methods.

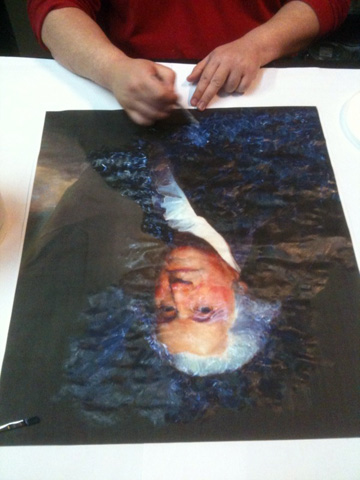

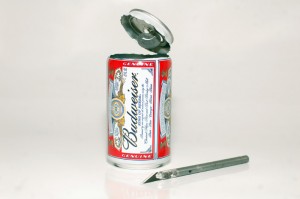

To cover one can with the label off another, you need to start by cutting off the top and the bottom. Aluminum cans cut easily with an X-Acto blade, snap-off blade, or box cutter. You don’t want to use a power tool like a band saw or jig saw, as the movement of the blade will shake the can and tear it uncontrollably. Once you remove the top and bottom, you can slice down the side to make a flat rectangle of metal.

Once you have the label cut out, it’s time to attach it to your other can. Many actors prefer not to drink soda or anything too sweet during a show, as it snots up their throats. They may also have special diuretic needs that may preclude using certain drinks. Your best bet is canned carbonated water. Whether you choose seltzer, club soda, tonic water, or sparkling water depends on personal preference, but also on what the cans look like. The club soda I’ve used here has a very non-descript can that does not make itself known after it has been covered.

Budweiser cans have the advantage of using white as a background color; you can use white electrical tape to attach the label. If you use a different brand, you need to experiment with other types of tape. Clear packing tape is a great option if you want to avoid a colored line along the top and bottom. Make sure whatever tape you use is strong enough to keep the sharp edges of the aluminum from cutting through.

Wrapping a can of carbonated water with a paper label is another way to go. This is a good idea if your printing costs are less than the cost of acquiring beer cans. The most difficult part of this is generating the artwork. Photographing or scanning the labels can leave unrealistic shading. If you are uncomfortable using a computer graphics program to assemble and even build parts of the labels from scratch, this may not be the route for you.

You can use tape to attach the labels on the paper ones as well, or an adhesive on the back (please excuse the messiness of the tape job in the photograph below). You may find the paper label is a lot duller than an aluminum one, so you can spray it with your favorite glossy or semi-glossy clear coat.

Whichever method you decide depends on the specifics of your production. There are many variables which can effect the look of the can from the audience, such as the lighting or distance to the stage. The production may have other peculiar blocking that will affect your prop choice. If the actors crush the cans, you may not wish to cover it in a second layer of aluminum, as it may make it harder or even more dangerous to pull that off.

Just remember, whatever your show needs, you “can” do it!