I’ve always thought it might be helpful to have a way of determining the identity and style of a chair by using visual means rather than by memorizing the names of all sorts of periods and styles. Sure, one can attempt to divide all chairs into forty distinct styles, but that is more helpful after the fact. As a props person, we are often faced with an existing chair, or picture of a chair, and we need to discern its style so we can find more like it. “This chair has kind of a Chippendale back, but with turned legs. What is it?”

Well, I haven’t accomplished anything like that, but I have come across a series of plates in the book Furniture Designing and Draughting, by Alvan Crocker Nye, published in 1907. These plates break down and illustrate the variations in each of the parts of a chair. If you remove ornamentation and look at just the basic shapes, you can design almost any chair from Western furniture history simply by picking and combining these variations. Even with the rudimentary distillations of chair design in  these plates, you can create 486,000 distinct-looking chairs.

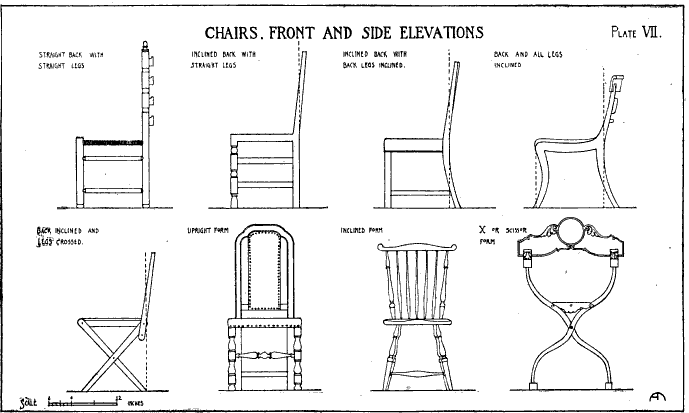

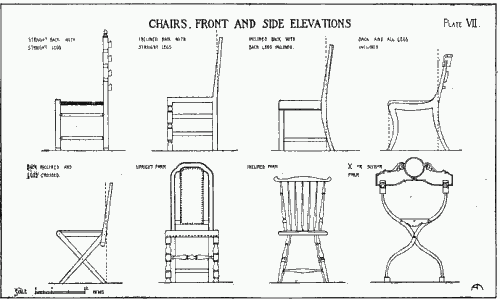

Plate VII above shows variations on how the legs can be oriented. In the top row, we see side elevations of a chair with a straight back and straight legs, an inclined back with straight legs, an inclined back with back legs inclined, and the back and all legs inclined. In the second row, we see the back inclined and legs crossed, than front elevations showing an upright form, an inclined form, and finally an X or scissor form.

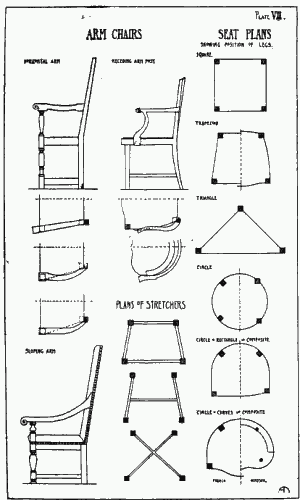

In Plate VII, we see the variations a chair’s arms can take. Under the “horizontal arm” drawing, we first see a plan showing how the orientation of the chair’s arm matches the shape of the seat. The two plans below it show how the arms curve out so the space between the arms is wider than the shape of the seat at the back. The two plans under the “receding arm post” show how the arm can be a compound curve or can be a continuation of the curve of the chair’s back. Finally, the elevation of the “sloping arm” chair shows that the arm can be higher in the back than in the front.

The plans of stretchers show how the reinforcing bracing of the legs can be arranged in either a box (trapezoid), an H, or an X (or cross) configuration.

Finally, the last column shows us different seat plans: square, trapezoid, triangle, circle, a circle and rectangle composite, and a circle and curves composite.

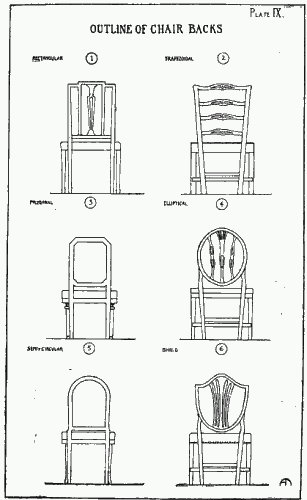

Plate IX shows outlines of common chair backs. 1) Rectangular. 2) Trapezoidal. 3) Polygonal. 4) Elliptical. 5) Semi-circular. 6) Shield.

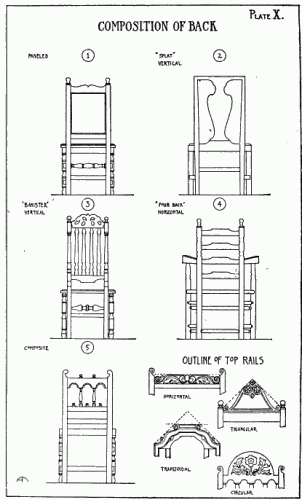

Plate X gives various compositions of the chair back. 1) Paneled. 2) “Splat”, vertical. 3) “Banister”, vertical. 4) “Four Back”, horizontal. Variations include the “Three Back”, or the much rarer “Five Back”. 5) Composite.

In the bottom right corner of the plate are four outlines of top rail shapes: horizontal, triangular, trapezoidal, and circular.