How were props used in Ancient Greek theatre? How were props made or acquired in Ancient Greek theatre? Here is a brief introduction, and also some resources to help you explore further if you wish.

The presence of props in Ancient Greek theatre

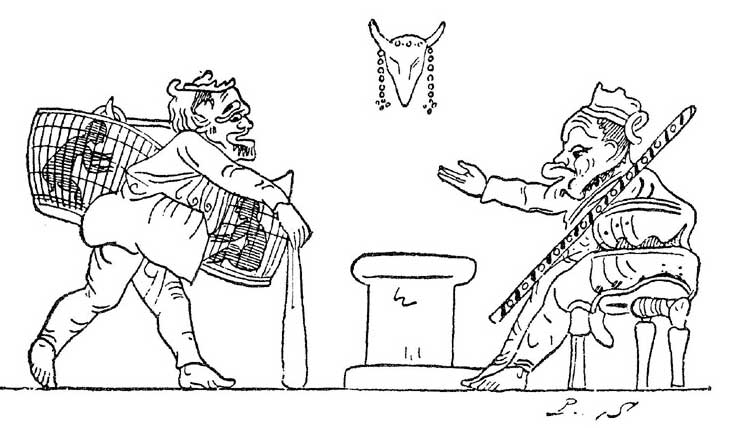

In the picture above, the actors have furniture, hand props and crowns. There also appears to be set dressing. You can see more images showing Greek theatre in action (scroll down about halfway through the page).

One of the most popular acting anecdotes involves a Greek actor named Polus. The tale was first recounted by Aulus Gellius:

Being at this time to act the Electra of Sophocles at Athens, it was his part to carry an urn as containing the bones of Orestes. The argument of the fable is so imagined, that Electra, who is presumed to carry the relics of her brother, laments and commiserates his end, who is believed to have died a violent death. Polus therefore, clad in the mourning habit of Electra, took from the tomb the bones and urn of his son, and as if embracing Orestes, filled the place, not with the image and imitation, but with the sighs and lamentations of unfeigned sorrow. (The Attic Nights of Aulus Gellius, pg. 68)

Though this anecdote is often used when talking about acting methods, it is also an interesting prop story.

Aristotle spoke of the opsis as one of the elements of tragedy. Opsis is the visual spectacle, which in Greek theatre includes the masks, scenery, costumes, and props. In Aristotle’s Poetics, he writes:

The decoration has, also, a great effect; but, of all the parts, is most foreign to the art. For the power of Tragedy is felt without representation, and actors ; and the beauty of the decorations depends more on the art of the mechanic, than on that of the poet. (The Poetics of Aristotle, translated by Twining, 1851, pg. 14)

Here, opsis is translated as “decoration.” “Mechanic” is how Twining has translated skeuopoios. Other translaters have described it as “stage machinist”, “costumer”, “stage manager”, “property man”, or “stage carpenter”.

How props were made or acquired in Ancient Greek theatre

Skeuopoios might be defined as a mask-maker, prop-maker, prop manager, or all of the above. Skeue may mean the trappings of an actor, such as equipment, attire, or apparel. Greek theatre used a lot of masks. These were impermanent objects, made of linen, wood or leather, and often included animal or human hair. This was probably the major job of the skeuopoios. If we think in terms of how theatre works today, we can imagine that the skeuopoios would have made other impermanent objects for the theatre. After all, if the theatre hired him to make masks, and they needed another object which could be made with the same skill sets, it would not make sense for them to seek out and hire another craftsman.

Perhaps the most comprehensive look at the economic and practical realities of ancient Greek theatre can be found in Peter Wilson’s The Athenian Institution of the Khoregia. In it, he describes the Khoregia, which was the cultural institution in Athens which produced the festivals, plays, and other performances featuring singing and dancing.

A khoregia will thus have brought the khoregos or his deputies into contact with a number of craftsmen. There is the skeuopoios or maskmaker. He may have also been the person who manufactured special theatrical clothing and other properties. Perhaps, as in Demosthenes’ case, a goldsmith for crowns, and even for gold-weave fabrics, will have been consulted. A less zealous khoregos could, we are told, visit the himatiomisthotes and hire second-hand costumes from him: even the scanty evidence at our disposal reveals the considerable range open to a khoregos to demonstrate his munificence or otherwise. (The Athenian Institution of the Khoregia, pp. 86-87)

J. Michael Walton posits that a number of people made all or part of their living off of theatre. Among these, he lists

…crane-operator (mêchanopoios), mask-maker (skeuopoios), costumier (himatiomisthês)… (The Cambridge Companion to Greek and Roman Theatre, pg. 288)

From this, we can see some of the specialization which exists in theatre today.

Unfortunately, none of the masks from Ancient Greek Theatre have survived today. The only visual evidence of masks and props are from vase paintings and sculptures.