The following first appeared in an issue of Theatre magazine in 1908:

by Mary Gay Humphreys

That for the most part virtue must be its own reward is the scene painter’s ethics of his own profession. When, as it sometimes happens, the curtain goes up on an empty stage, and the audience breaks into involuntary applause over the beauty of the scene, such are his crumbs of comfort, and he takes them thankfully.

His own standards are much higher than he is able to realize. In this respect there seems to be but little difference between his attitude and that of the painter regularly accredited to the Fine Arts. But at no previous period is his discouragement greater than at this moment, when to the man in the orchestra scenic productions seem to have profited so greatly by modern inventions and scientific developments, as that, for example, of the electric light. Nor on no other man has later managerial conditions borne more hardly.

“There is no book that gives the history of scenic art. It would be too sad. It would tell only of disappointed hopes, of melancholy failures.”

This was said by Mr. Unitt in his interesting den at the Lyceum Theatre:

“Scene painting differs from the paintings known as among the Fine Arts only in degree. The principles are the same as in miniature painting. The only difference is you have forty feet of canvas. A portrait must resemble the subject more minutely than the scene resembles a situation, but that does not concern the principles involved. But, unhappily, to say that a picture represents scene painting is to make a disagreeable criticism.

“But it should be remembered that in painting, as the term goes, the artist does as he wishes; he consults no ends but his own. It is not so with the scene painter. His painting furnishes only the background, and this as a picture is likely to be thrown out of key because the other parts, of which he has no control, are not consistent with it. The lighting of the stage, for example, may not agree with the atmosphere the scene painter has given the scene. He also has to contend against costumes out of key, and as the living element of the picture is most prominent, the scene suffers.

“But nothing has tended to retard the development of scene painting as has the decay of the old stock companies. In those days the scene painter was part of the working staff of the theatre, and in daily intercourse with his principals. It took time, if you will remember, to produce such scenes as those in ‘The Amazons.’ This could be only accomplished by having a manager with artistic perceptions, and a staff that felt that pride and enthusiasm which must accompany good work.

“The method of production is now entirely different. The scene painter is not part of the theatrical staff. His is an employee of a firm. He is required to produce as rapidly as possible the scenery for perhaps twenty plays. The greater number of these will be failures, and others must be ready to take their place. This means a large plant and more rapid work. The scene painter cannot follow up his work; frequently he never sees it afterward. He has absolutely no opportunity for individuality, and naturally does not take the same interest as he did in that artistic atmosphere engendered when he was a member of the staff of a theatre.

“The conspicuous defect to-day in stage production is the lack of team work. The men who now control these matters are not distinguished for their keen artistic sense as was the manager in the old days. The commercial element, that has to be considered in view of the number of plays and possible failures, requires that the plays be put on as cheaply as possible. Suppose the scene painter attempts to carry his point and the play fails. He would probably have to listen to such comments as:

“‘Now, if you had put that girl on the fence and thrown a lot of color around her, the play would have gone far better. See?'”

Stage scenery and the men who paint it. M. G. Humphreys, il. Theatre 8: 203-4, v-vi, Aug 1908.

Thank you for posting this! It is so interesting! It is a great thing to read in relationship to the Twin Cities Scenic Collection-The overall collection is the only one of its scope in the United States, and uniquely documents the technical environment of the popular stage during the late-nineteenth through early-twentieth century. Renderings and materials from the type of scene painting “firms” that the author of the article speaks about, are archived at the University of Minnesota and can be seen online at http://umedia.lib.umn.edu/scenicsearch.

It’s also interesting that the attitude by Mr. Unitt regarding these scenic painting companies feels a lot like how a lot of scenic painters regard the printing of backdrops these days.

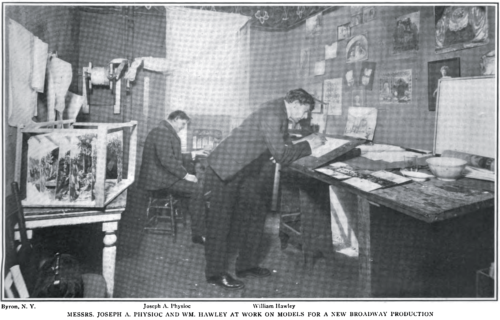

I really LOVE the photo also!