The following comes from the May 3, 1903 issue of The St. Paul Globe:

When the curtain drops at the close of every act of a drama or opera it is the signal for the players to rush for their dressing rooms, some of the men in the audience to troop up the aisles in search of—a change of air, and the women to chat and—possibly to note what the other women are wearing.

But there is another class of individuals for whom the falling of the curtain means business, and the liveliest kind of business at that. They are the “stage hands.”

As the curtain strikes the floor a stentorian voice cries:

“Strike!”

“Strike!” echoes another equally robust voice, and instantly there is a commotion on that stage that would bewilder a bystander, if he were permitted there at such a time—which he is not.

The first voice is that of the stage manager of the company playing at the theater. The second is that of the stage carpenter attached to the house. The commotion is the scurrying about of the stage hands, the property men and the electricians whose duty it is to clear the stage with the greatest possible celerity of all scenery, furniture and lighting paraphernalia that encumbers it. For perhaps the first act presented a street in a large city or the parlor of a rich man’s mansion, and the second is to picture a country lane or the wretched hovel of the poor but virtuous. Hence this bustle.

The writer was privileged to watch the rapid clearing and transformation of the stage at the Metropolitan opera house the other night between the acts of a spectacular play. It was a confusing spectacle. Men rushed hither and thither, some shoving and bracing up scenery, others carrying tables and chairs and sofas, others placing incandescent lamps, “bunch” lights, strip lights and calciums, and still others way up in the loft or “flies,” letting down painted canvas or “drops.”

While they all worked with marvelous celerity, it was noticeable that they never collided with one another or became in the slightest degree confused or uncertain. It was like clock work.

It was also noteworthy that not a single man who moved scenery, even so much as touched a chair or table or clock or mantel, while the men who handled the furniture and all other properties never laid a hand on a piece of scenery.

Seem to Ignore Each Other.

The scene shifters religiously dodged the furniture and the property men ignored the scenery. The men who manipulated the lighting apparatus ignored both.

This is all a part of the system devised to expedite a change of scenery. It prevails in every theatre in the land.

Taking the Metropolitan as a perfect example, which it is, of a well managed stage, you will find that its little army of stage hands number 11 men—the stage carpenter who is in charge of the stage and 10 men, to all of whom are assigned specific duties.

Two of these men, one on each side of the stage, handle nothing but the scenery, two men in the flies, one on each side, 25 to 30 feet above the stage, raise and lower the painted drops that furnish the backgrounds of the various scenes, the electrician and his assistants manipulate the complicated switch board that regulates every light in the entire theater, and finally the property man and his assistants are intensely busy bringing on and carrying off all the furnishings, the sofas, chairs, tables, vases, clocks, table ware, imitation fruit, papers, match safes and a thousand and one things used and handled and tasted by men, women and children.

When the stage manager yells “strike,” the electrician turns up the lights in the auditorium, as well as the border lights over the stage, that the men may see what they are doing, and at once proceeds to remove all the electric lighting appliances that belong to the scene. Then the scene shifters rush on, unloosen the braces, seize the scenery and push it off piece by piece, while the property man dodges and ducks between, under and around them carrying off the furniture and everything else portable. In the meantime the flymen raise the drops.

In perhaps three minutes the stage is as empty as a barn floor, when suddenly partitions, doors, bay windows, or like as not fences, bridges, trees, castles or huts are rushed on and braced up. As these articles are placed in proper relative positions, the flymen let down a painted canvas, it may be a garden or forest, a mountain or plain “expanding to the skies,” or the background of a palace. The scene is scarcely set when the property men are there with the furnishings that give it the semblance of reality, a well or pump, a fence, a bench, a swing if it be a country dooryard, or a piano, a cabinet, rich rugs and tapestries, vases, mirrors and the like, if it be the interior of a fashionable drawing room.

Needs the Ten-Light Effects.

Still the  scene does not look like the real thing to you, standing behind the curtain, with the garish border lamps making it top-heavy with light.

But suddenly there is a cry: “Clear the stage!” The player or players to be discovered on the scene take their places, the electrician lowers the top lights, substituting perhaps a soft tint of red or blue, according to the atmosphere desired, the footlights go up, so does the curtain, and the audience beholds a faithful and oftimes striking picture, in which latter event it applauds.

It must not be thought that stage hands work only while the show is in progress. On the contrary they labor all day as well. At the Metropolitan they are all required to report at the theater at 9 o’clock every morning except Sundays. There is something to keep them busy until the show ends at night. Of course they are allowed plenty of time for their meals. But the stage is never left alone after 9 o’clock in the morning.

The crucial test of the skill of stage hands presents itself when they are required to make a complete change of scene in pitch darkness, while the curtain is up. In these cases it is essential that the work be done with extreme precipitation, for no audience will tolerate sitting in complete darkness for many minutes or many seconds for that matter. To accomplish this task with expedition and without mishap or mistake, the stage hands must be might familiar with every inch of the stage and the property man know what he is handling even in the dark, otherwise some extremely ingruous combination might be revealed when the lights go up.

Some awkward hitches are occasionally noted on first nights of massive productions, but after one experience with the scenery of the play, competent stage hands are thoroughly at home with it.

Large attractions demanding elaborate scenic investiture invariable carry some stage hands of their own. All are equipped with a stage manager and property man, and if the scenery is heavy, a stage carpenter and other assistants.

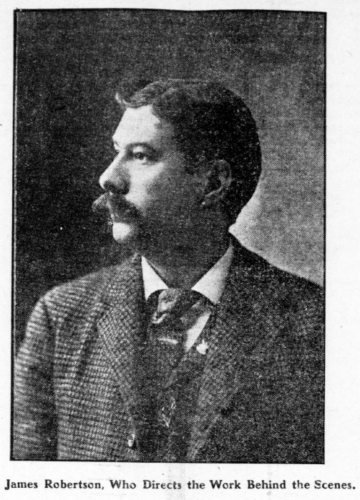

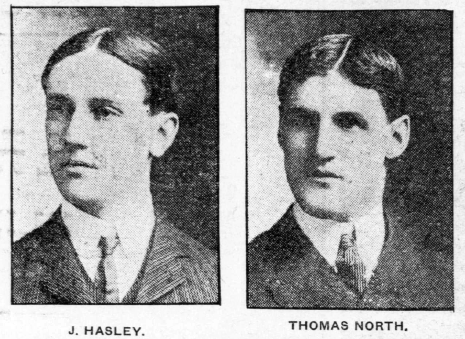

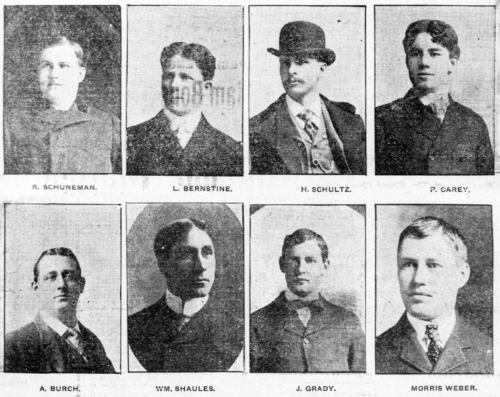

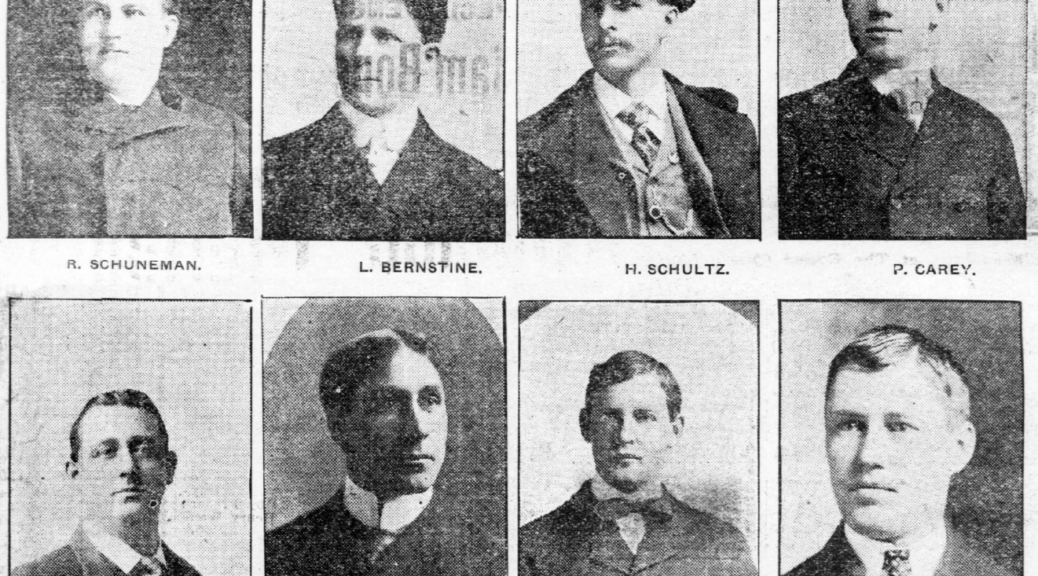

The accompanying cuts are photographs of the force of stage hands at the Metropolitan which is in charge of James E. Robertson, the stage manager of the Metropolitan opera house stage. The property man is William O’Brien, and Patrick Cary is the electrician. The names of the others appear with their pictures.

The important part these gentlemen play in the successful presentation of any play, especially of a spectacular character, needs no explanation.

The Saint Paul globe. (St. Paul, Minn.), 03 May 1903. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn90059523/1903-05-03/ed-1/seq-18/>

Important to those who never see these faces.

Important people whose faces we never see .