As some of you may have noticed, this site was difficult to get to for the last week, and hasn’t been updated for awhile either. My hosting service had a server crash, and it has taken them some time to get everything back up and running. The site has been extremely slow to load since last Wednesday, and virtually impossible to update. It looks like everything is back to normal now, as evidenced by the fact that you are reading this.

When last we left, I was talking about how to build a dragon—the creature named “Fafner” from the opera Siegfried, to be exact. The Metropolitan Opera House has had several over the years. The first was built by William De Verna in 1887. A new one was constructed in 1913, refurnished in 1937 and finally replaced with another dragon in 1947 (the dates in my previous article were a little off). This last one was built by the mechanical magicians at Messmore and Damon. Since writing that last blog, I have found some additional dragons which existed in between those three.

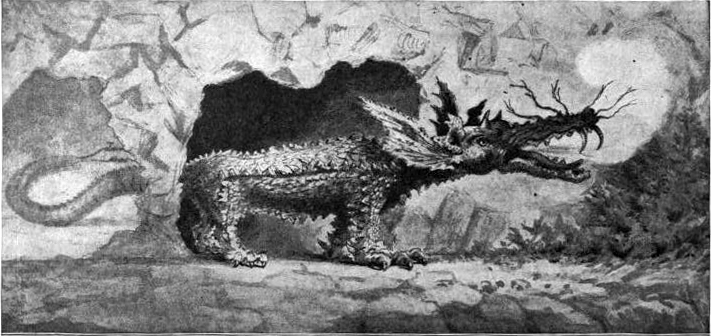

The dragon in the illustration was created for the 1896 production by a Mr. Siedle, described as the property master of the Metropolitan Opera House. To construct this monster,

the head of the dragon was modeled in clay, and each line and horny scale and boss was the result of careful calculation. After the head was modeled, a plaster of paris mold was taken from it, and from this another plaster cast was made, upon which the actual head was built up out of papier maché. After the papier maché work was finished, it was painted dark green; different shades were, of course used.

The body of the dragon is of cloth; the legs and feet are not attached to it, but are put on by the two men who operate the dragon. The feet and claws of the dragon are pulled on by combination overalls and boots…

The tail consists of a number of sections of wood articularted by means of hinges. It is covered with painted cloth.

The dragon holds two men inside who operate it. The man in front wears a heavy belt that supports the wires for the eyes and the rubber hose for the steam to his nose. The eyes are lamps covered in painted silk. The man in the back is the one who actually controls the head, using a lever which swings on the front man’s shoulders. The man in the front also controls the jaw, antennae and tongue.

The wires and hoses run off stage through the wings. Two stage hands are back there, one to operate the steam, the other the lights.They also help the men get into and out of the dragon suit. A number of stage hands are also needed to guide the men backstage while wearing the suit.

In a New York Times article from 1910, Edward Siedle, here described as the technical director of the Met (though his job duties include the props), talks about the dragon.

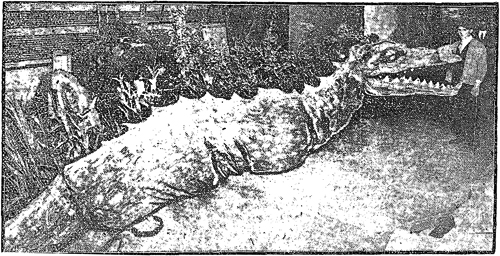

Mr. Conried imported a German dragon when he first put on ‘Siegfried.’ Later, I had another dragon made in my own shop, as the dragon was not altogether a success. This one in turn perished in the San Francisco disaster [ed: the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, during which the Met Opera company was on tour. The scenery and props for all the operas on that tour, as well as many musical instruments, were destroyed], so that the present dragon has been made since then, and is the most successful of the three. It was made after the manner of the first one which I made, but it has modifications. This little stage toy cost in the neighborhood of $350.

This dragon was made for the 1903 production at the Met. I’m guessing that this is the same Siedle who made the 1896 one; they sound remarkably similar. He continues:

Fundamentally it is a thing of canvas, but it is painted and molded with various materials. When it is not in use it will fold up and can be put into a small box.

This dragon shakes its bristles, its eyelashes and its eyelids move, vapor comes through its nostrils, and its head has three separate movements. Two men are concealed inside of it. Their legs form the legs of the dragon and their shoulders support the upper framework. From the inside they regulate the movements of the bristles, the winking of the eyes.

This dragon also has electric lights for eyes. The head can also be controlled from offstage with a series of thin wires. A total of seven stage hands are in control of the dragon while it is on stage. The singer providing the voice, meanwhile,was hidden in bushes midstage singing through a megaphone.

From here, we only have to look at the 1972, 1987 and the currently running 2011 productions of Siegfried to complete our look at all the Fafner dragons used by the Met since its inception. But that is a tale for another time.

Sources:

Hopkins, Albert A., and Henry Ridgely Evans. Magic: Stage Illusions and Scientific Diversions, including Trick Photography. New York: Munn &, 1898. pp 332-4.

“The Mysteries of Staging a Grand Opera.” New York Times 27 Feb. 1910.