The hot glue gun is one of the main tools in a props person’s arsenal. Some people love them, some despise them, but at one point or another, all will use one. They can also be referred to as hot melt glue guns and hot melt adhesive guns. They use sticks of hot glue, or hot melt adhesive, thermoplastic adhesive, or thermoplastic cement, depending on your preferred nomenclature.

So who invented the hot glue gun, and how did it come to be? If we Google the phrase “who invented the hot glue gun”, we find the following results:

The first few results list “Robert Brooklyns” as the inventor. Let’s see what a Google search on him turns up:

When I did the search, Google returned around 83 results. All of them basically parroted the same sentence. Basically, one site (Answers.com is my guess) made this completely uncited statement, and it has been echoed throughout content farms and superficial sites across the internet. No one with this name shows up in a deeper search through books or patents, which seems surprising, given how important the hot glue gun is.

You may have noticed in the first image that a result shows up with an obituary for George Schultz, whom the Boston Globe calls the “inventor of the first industrial glue gun”. According to the Globe, he founded Industrial Shoe Machinery in Boston in 1954, which he sold to 3M in 1973. Somewhere along the way, he invented the Polygun, the “first industrial glue gun”. 3M manufactured hot glue guns under the name “Polygun” until 2006, when they changed the name to “Scotch-Weld”.

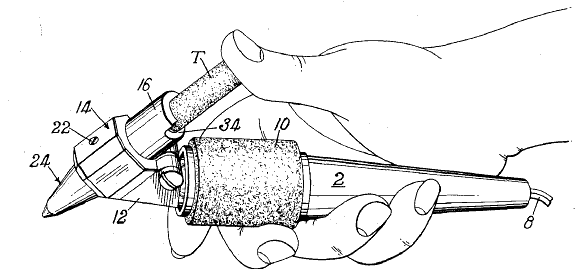

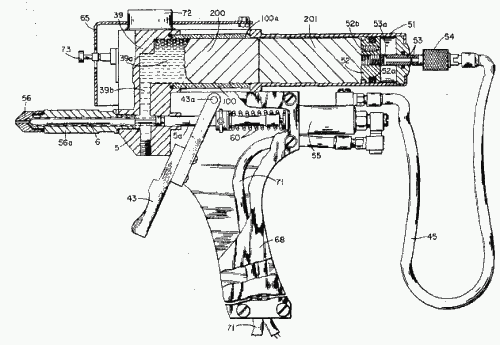

The earliest related patent I could find for George Schultz was for an Apparatus for Dispensing Thermoplastic Material. It was issued on June 2, 1971.

The diagram shows a glue gun with a trigger, but the glue is held in an internal reservoir rather than fed through as sticks. While Mr. Schultz was certainly the inventor of a hot glue gun, he was hardly the inventor of the hot glue gun.

The Wikipedia article on adhesives has an uncited claim that thermoplastic adhesives were invented in the 1940s by Proctor and Gamble by a man named Paul Cope. Again, this becomes hard to verify, because innumerable content farms merely copy the Wikipedia article, and most of the search results are variations of this same initial claim (many have the same exact wording). At least we can find evidence that Paul Cope was a real person who worked at Proctor and Gamble. He even filed a number of patents having to do with improvements in packaging. Whether he had anything to do with thermoplastic glues seems to be a moot point, as mentions of thermoplastic adhesives can be found in literature and patents much earlier than that, as far back as 1907.

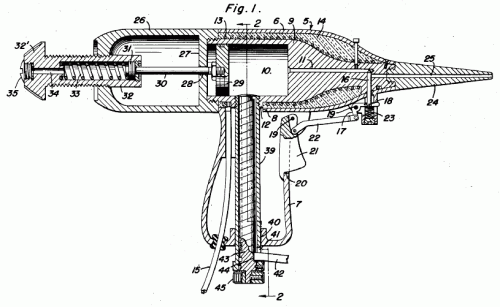

Perhaps the earliest proto-hot glue gun was this Plastic Extrusion Gun created by William R. Myers and Albert S. Tennant in 1949. The device was created for melting plastic and extruding it onto fishing hooks to manufacture fishing flies. The plastic was fed into the device as ribbons rather than as sticks, and it did not use thermoplastic adhesive. Regardless, many of the parts and components of a modern hot glue gun are there, and later inventors referred to the Myers and Tennant plastic extrusion gun quite a bit in their patents.

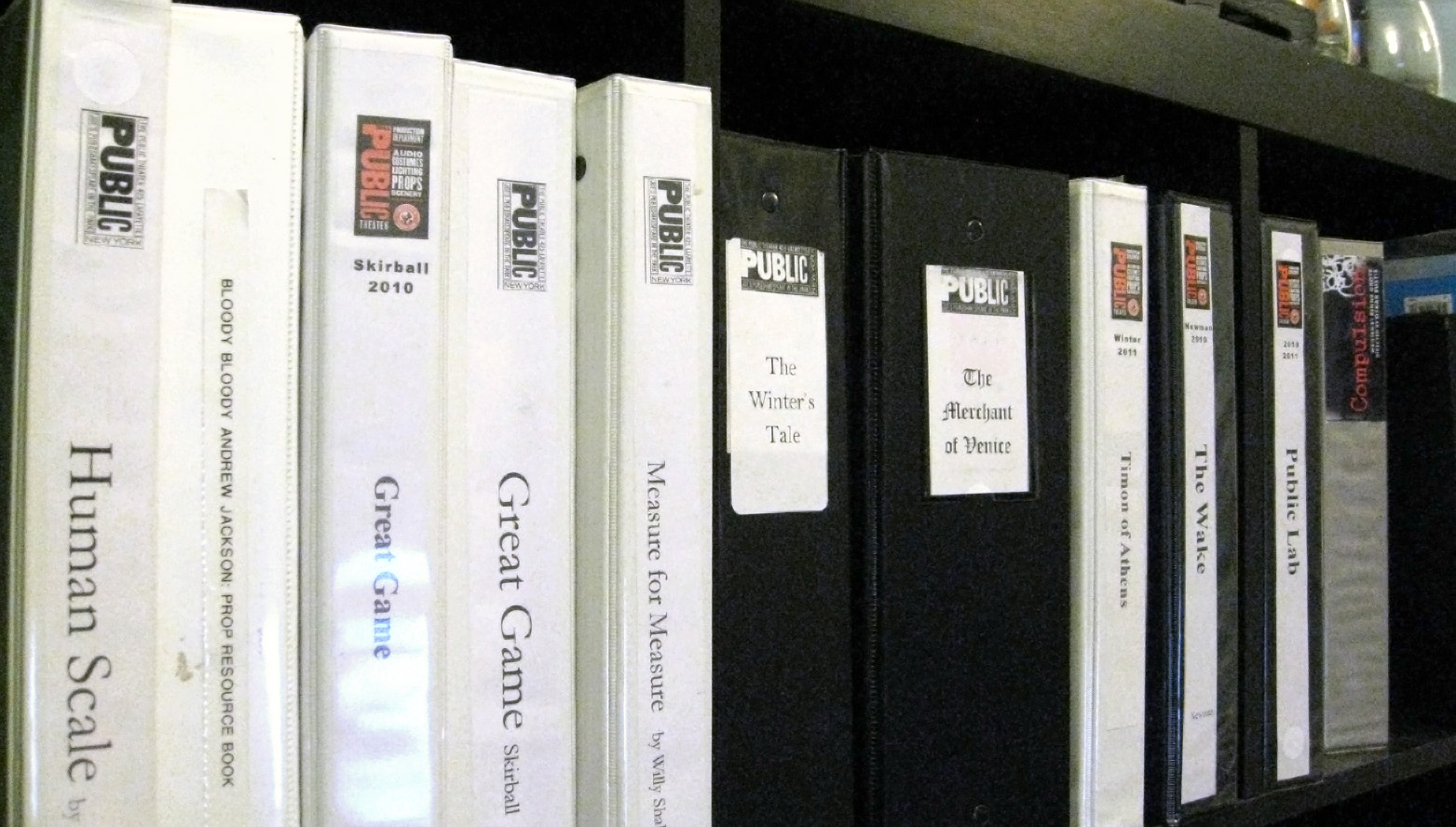

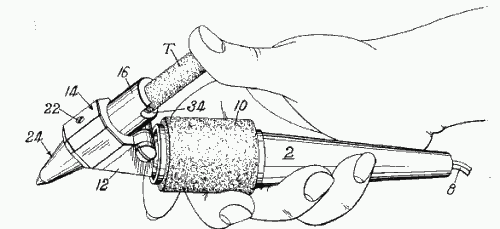

In 1965, Hans C. Paulsen, working for United Shoe Machinery Corporation, was granted this patent for the Portable Thermoplastic Cement Dispenser. It predates Schultz’s invention by six years.

That December, Popular Science ran an article about this glue gun, named the “Thermogrip”. The article proclaims “A black plastic pistol with an electrical heating element and an aluminum nozzle that extrudes hot-melt glue is one of the newest tools for home and shop.” I find the Thermogrip notable for its use of glue sticks and for the fact it was marketed and sold to home users, as opposed to previous glue guns which were tailored for specific industrial processes. I would consider this to be the first “hot glue gun” in the sense which we are most familiar today.

As with any invention, it is perhaps futile to try and trace its invention to a single person. The hot glue gun relies on a number of parts and components, such as the development of thermoplastics, the evolution of plastic extrusion guns, and the societal need for a portable device which accomplishes all of this. The modern-day glue gun we all know and love has any number of features and improvements which were not present in the earliest iterations.

That said, the hot glue gun was certainly not invented by a (perhaps imaginary) man named Robert Brooklyns, and hot glue was not invented by Paul Cope. This goes to show how easily an unverified claim can infiltrate the Internet. Remember kids, more search results in Google does not equal more reliability. An unsourced claim is still an unsourced claim even when it shows up on thousands of websites.